Watch: This is the most expensive floral perfume

Posted on June 9th, 2025

In the world of luxury perfumes, jasmine and rose are the king and queen—no floral fragrance is complete without them. And some 100,000 farmers in a tiny area around Madurai produce the world’s best jasmine that powers scents by Dior, Guerlain or Tom Ford. It takes more than 1,000 kilos of these tiny milky-white flowers to make just one kilo of jasmine oil—an oil that sells for nearly ₹4 lakh. The jasmine sambac or Madurai jasmine is considered a symbol of love, beauty and purity. In this video we find out how the unique geography and climate of Madurai produce the ‘intoxicant queen of the night’ that goes into a bottle the world’s rich and famous are ready to splurge on.

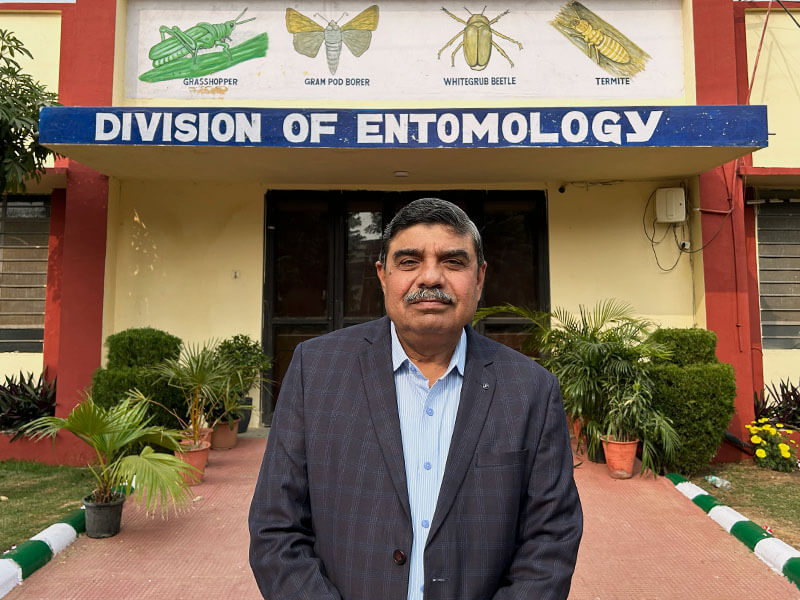

Why precision agriculture is India’s best bet against climate uncertainty

Posted on June 9th, 2025

The Indian agriculture has always been a story of grit and resilience— navigating the rhythms of monsoons, shifting seasons, and evolving market demands. But today, the stakes are far higher. Climate change is no longer a distant threat—it is a present and growing challenge impacting millions of farmers every day. Unseasonal heatwaves, erratic rainfall, and extreme weather conditions are disrupting traditional farming cycles, threatening both livelihoods and national food security. India is among the most climate-sensitive agricultural economies in the world.

According to the Indian Meteorological Department, 2023 was India’s fifth warmest year on record, with severe heatwaves affecting over 20 million hectares of farmland. Meanwhile, the Economic Survey 2023–24 reports a 4–6% decline in wheat and rice productivity in some states over the last five years—a stark indicator of the mounting pressure on our food systems.

In late 2024, farmers in Rajasthan faced temperatures soaring 2–7°C above normal, prompting a shift to more heat-resilient crops. At the same time, flash floods devastated large tracts of farmland in Himachal Pradesh and Kerala. With over 55% of India’s agricultural land still dependent on monsoons, the need to transition from reactive to predictive farming has never been more urgent. To feed 1.4 billion people sustainably while conserving natural resources, India must accelerate the adoption of climate-smart farming practices—anchored in data, powered by technology, and driven by insights.

Precision farming: A sustainable solution

The answer lies in precision agriculture—a transformative approach that combines technology with traditional wisdom. By leveraging real-time data, remote sensing, AI, and IoT, farmers can make better decisions about when, where, and how to farm. This shift from input-heavy to insight-driven agriculture is not just sustainable; it is smart economics.

Precision farming helps optimize every drop of water, every unit of fertilizer, and every minute of farm labor. Variable rate technology (VRT), for example, enables targeted application of nutrients and crop protection, reducing input costs by up to 30%. GPS-guided sowing and harvesting increase efficiency and minimize wastage. Netafim India has been at the forefront of this transformation.

Drip irrigation, a cornerstone of precision agriculture, delivers water and nutrients directly to the plant root zone. Studies show it can save 30–70% of water while boosting crop productivity by 20–60%. In water-stressed regions, this can mean the difference between crop failure and a bumper harvest. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) estimates that adopting precision farming methods can increase productivity by 15–25% while reducing input usage by up to 35%. These are not just numbers, they represent better incomes, reduced risk, and a pathway to climate resilience.

Data: the new fertilizer

Technology is becoming the new lifeline of Indian agriculture. With over 1,300 AgriTech startups and a projected market value of $24 billion by 2025 (as per FICCI-EY), innovation is rapidly democratising access to digital soil maps, crop analytics, precision irrigation, and weather forecasting.

Startups are offering AI-based crop advisories, drone-enabled field operations, and market linkages, helping farmers make better decisions and improve profitability. These innovations, once considered niche, are now gaining scale thanks to robust policy support and expanding infrastructure. Government initiatives such as the Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) for agriculture, Per Drop More Crop under RKVY, and PM-KUSUM for solar irrigation are laying the foundation for a digitally connected and tech-enabled rural economy. The Unified Farmers Service Platform (UFSP) is an important step in integrating critical services—from weather alerts and crop insurance to credit access—into a unified, farmer-centric ecosystem. Together, public policy and private innovation are enabling a shift from reactive to proactive agriculture. India is not just digitizing farming—it is futureproofing it.

Digital tools are no longer optional, they are essential. From soil health cards to satellite-based yield forecasting and blockchain-enabled supply chains, data-driven technologies are redefining how farms are managed. The result is greater resilience, reduced input dependency, and improved environmental outcomes. Schemes like Agri Infra Fund, and the National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) are accelerating this transition. By promoting solar irrigation, post-harvest infrastructure, and precision solutions, these policies are making climate-smart agriculture accessible, particularly for smallholders. The Government’s push for DPI is helping ensure that even marginal farmers benefit from these innovations. Seamless service delivery through digital platforms is bridging information gaps and enabling smarter, faster decisions at the farm level.

As India’s population is projected to touch 1.7 billion by 2050, food demand is expected to rise by nearly 70%. Meeting this demand sustainably—without expanding arable land—requires a fundamental shift in how we farm. As India moves toward its centenary milestone in 2047, we must ensure that every farmer is climate-ready, tech-enabled, and financially empowered. Precision agriculture is not just about increasing yields—it’s about making farming future-proof. By adopting sustainable practices, optimizing resource use, and embracing innovation, we can build a farming ecosystem that is not only more productive but also more resilient to climate shocks. This is essential not just for farmers, but for the nation’s food and economic security.

It’s time to reimagine Indian agriculture—not just as a sector, but as a smart, sustainable ecosystem rooted in tradition and driven by innovation.

(Vikas Sonawane is COO, Netafim India)

How citizen science is revolutionizing water management in Indian agri

Posted on June 9th, 2025

Across India’s farmlands, the water table is dropping faster than ever, and the data meant to protect it is falling short. Decisions that shape the future of farming are still made with outdated maps, incomplete surveys, and distant models that miss what’s right beneath the soil. But that’s beginning to change, not through high-tech labs alone, but through a new force reshaping rural India: farmers themselves.

Agriculture consumes more than 80% of India’s water, yet the way we manage it has long relied on incomplete data and top-down decisions. Government assessments often focus on macro-level indicators, which may not fully account for site-specific variables like borewell depth or moisture levels in the soil. Check dams are built, but dry up. Aquifers are tapped, but rarely replenished. And all the while, farmers are left to make high-stakes decisions: when to plant, how much to irrigate, what to expect from the next season.

But what if the very people facing the brunt of these choices were equipped and empowered to inform them?

The data dilemma

A recent study by the Sattva Knowledge Institute found that every year, corporations pour over ₹265 crores into water conservation efforts. But here’s the catch: over half of that money goes into one-time studies that often remain behind paywalls. The data doesn’t reach the hands of farmers. It doesn’t help policymakers come up with long-term solutions. And crucially, it rarely captures the real, ground-level dynamics: the borewells that go unnoticed, the aquifers that silently dry up.

Official monitoring systems mostly track shallow wells, missing the deeper borewells farmers actually depend on. The result? Skewed estimates, misplaced interventions, and growing mistrust between rural communities toward government schemes.

The Citizen Science Solution

A different approach is helping shift this dynamic – treating farmers as citizen scientists, partners in gathering, interpreting, and acting on water data. It’s not about replacing satellites or experts. It’s about connecting their insights to what’s happening on the ground.

Open-source platforms like CoRESTACK are leading the way. In Tamil Nadu’s Kaveri Delta, for instance, farmers worked with researchers to map over 800 wells, revealing that borewells are drilled up to ten times deeper than those the government tracks. That single insight has changed how irrigation decisions are made, moving from guesswork to evidence-based planning.

Grassroots tech with real impact

Government-backed tools are also stepping up. The Jaldoot App, launched by the Ministry of Rural Development, trains village volunteers—aptly named Jaldoots—to measure well levels twice a year. It’s simple, low-cost, and effective. These measurements help identify water-stressed areas, informing farmers when to sow, how to conserve, and where to focus community efforts. Unlike expensive corporate studies, this model is scalable, grassroots, and built to last.

In Maharashtra, a Water Budget Dashboard developed by IIT Bombay ran into a common problem: the satellite-derived soil data wasn’t accurate enough. The fix? Turn to farmers. By incorporating their observations on local soil texture, the project created a high-resolution tool that provides hourly water balance estimates. That’s not just data, that’s real-time guidance farmers can use.

From data collectors to decision-makers

It’s not just about collecting better data, but about who gets a seat at the decision-making table. The Composite Landscape Assessment & Restoration Tool (CLART), developed by the Foundation for Ecological Security, enables even semi-literate rural communities to design water harvesting structures tailored to their land. In over 1,500 Gram Panchayats, farmers are designing ponds and recharge systems that actually work, because they’re based on local knowledge, not generic templates.

These efforts succeed because they blend top-down and bottom-up data. Satellite platforms like India-WRIS offer invaluable regional insights on groundwater levels, cropping patterns, and rainfall trends. Complementing these, however, is the need for more granular data to inform decisions at the village level. CoRESTACK takes it further, mapping wells with sub-meter accuracy. Yet even that’s not enough without farmer input. Only they can report on borewell use, seasonal water shifts, or sudden changes in recharge patterns.

Building the future together

The path forward is clear. Corporates must move beyond isolated studies and partner with local communities. Funding open-data ecosystems, supporting NGO-led training, and embracing farmer-generated inputs will create a shared knowledge base that benefits everyone, from the policy table to the paddy field.

Platforms like India Observatory and CoRESTACK can democratize access to essential indicators—drought frequency, soil moisture, and crop suitability. When farmers are equipped with this data, they don’t just adapt, they innovate. They become co-authors of their future.

The new water stewards

This goes beyond just about apps or dashboards, it’s about changing how we see our farmers. They’re more than beneficiaries; they’re active participants, planners, and custodians of India’s water resources. Furthermore, tools like Jaldoot and CLART prove that local knowledge, when properly harnessed, can outmatch even the most sophisticated models in relevance and impact. As India stares down a looming water crisis, embracing citizen science isn’t just smart – it’s essential.

The answer to India’s water woes won’t come solely from boardrooms or bureaucracies. It will come from fields, farms, and village wells, where data meets lived experience, and where farmers, armed with insight and agency, reclaim their role as guardians of the land.

(Debaranjan Pujahari is a Partner at Sattva Consulting, where he leads the Agriculture Practice Area, and Kangkanika Neog is an Engagement Manager with the Agriculture Practice at Sattva Consulting.)

Jasmine’s journey: From the fields of Madurai to French luxury perfume

Posted on June 2nd, 2025

Seethapuram is a small, squalid village home largely to Telugu-speaking Naickers, at the foot of the Western Ghats, some 50km northwest of Madurai. Overnight showers, unseasonal in late March, make it hard to see puddles from open sewers in the darkness of 3am.

The village is not just stirring; its people are out and about.

Chinnaraman, 54, and his wife Murugayi, 48, are both dressed in sky-blue half-sleeved shirts. She wears hers over a sari, and he adds a grey flannel jacket on top. They are ready to leave for their farm, a ten-minute ride over undulating terrain on a grunting 100cc bike.

A multicoloured rooster, perched on a moringa branch outside their newly built home painted in grape purple with psychedelic ceramic tiles, has timed its crow to match their routine.

Walking briskly along slippery grass bunds, barefoot, they switch on the heavy-duty lamps strapped to their foreheads. The first order of business is harvesting roses.

Two fingers—index and thumb—a twist and snap. Snap, snap, snap. After an hour and about two thousand flowers, it’s time to move on to the jasmines in an adjoining section of their three-acre land.

The night bloom

Harvesting jasmine, or specifically, jasmine sambac, commonly known as Madurai malli, requires the same two fingers but no snap. Pffff, pfff, pfff… a hoovering sound only audible to the fingers. The jasmine buds are far more numerous and more delicate than roses. They go into the sari and lungi pouches like a kangaroo’s marsupium. There is no time to catch a breath or engage in small talk. In the darkness dotted by headlamps, they need to be alert to the rustle of insects and even snakes. This being hardcore Ilaiyaraaja country, his music blasts through PA systems of distant temples celebrating all-night fests. Humming along is the only form of distraction.

In the crimson gauze of dawn, when moonlight and the headlamps are in a gentle tussle, the closest flat-top hill, blue-black and covered in a tablecloth of cloud, comes into view first. This truel-de-lux of natural and artificial sources makes the jasmines, springing forth from the red soil, seem like stars in an upside-down sky. The pink roses glint like rubies, and the pale yellow chrysanthemums glow, positively neon. The cattle egrets start swooping to the ground, their flight elegant, keeping time with the peacocks’ vuvuzela-cry. The couple’s farm of flowers, in that moment, is as fetching as their village is bleak.

A race against time

By 7.30am, when the magic of light and sound has faded and the heat draws sweat from every pore, Chinnaraman and Murugayi have collected two kilos of jasmine. If Chinnaraman can reach the wholesale market in Nilakottai, six kilometers away, by 8am, the flowers will command the day’s peak price of ₹350–400 per kilo, earning a handy ₹800 for their first shift.

This is where the world’s best jasmine, the Madurai malli, grows. And this is the kind of backbreaking work that gets it to travel the world.

It can reach the local temples for puja throughout the day. It can rest around the neck of stone statues that are worshipped, be strung into garlands and the strings that women wear. It can catch the afternoon flight to cities like Mumbai and Delhi, even Dubai, Singapore or San Francisco, where it’s coveted by the Indian diaspora. It might even end up in a bottle of super-luxury perfume that the world’s rich and famous are happy to splurge on.

Ancient roots

“Jasmine and rose are the king and queen of any luxury perfume with floral notes you can think of. And the jasmine sambac, or Madurai malli, is the soul of any high-end floral perfume made by brands such as Dior, Guerlain or Tom Ford,” says Raja Palaniswami, the founder and director of Jasmine Concrete, the largest floral extraction firm in India based in Madurai.

Of the nearly 200 species of jasmine, some 90 grow in India. The most prized among them is jasmine sambac, known globally as Arabian jasmine—a somewhat misleading moniker since it is native to India and this is where it is grown on the biggest commercial scale. Besides Madurai, it is cultivated in other parts of Tamil Nadu, the Mysuru region, Andhra Pradesh and even Bengal and the northeast.

Madurai is one of the most ancient cities in India, the literary and cultural heart of Tamil civilization. During the Tamil Sangam era—estimated from around 300 BCE to 300 CE—Madurai served as the epicenter for academies of poets and scholars that nurtured classical Tamil literature and language. The city’s ancient Meenakshi Temple and the legend of the divine wedding of Meenakshi and Shiva’s most enchanting form, Sundareshwara, are inextricably linked to Tamil culture.

A Sangam Tamil poem recounts the generosity of a local chieftain, Pari, who could not bear to see a delicate jasmine creeper lying on the hard forest floor. He gifted his royal chariot to the plant so it could twine itself around the wheels and rest more comfortably.

Bold and heady

Modern Madurai is a pulsating city, loud and proud in every way. Its festivals are boisterous, its food bursts with big flavors, and even the banners announcing weddings or mundane ceremonies like ear-piercing are larger than life. Madurai’s influence on Tamil culture is so outsized that it can verily be called the Punjab of Tamil Nadu.

The jasmine sambac, or Madurai malli, is no different. This tiny milky-white flower, no larger than a thumbnail, has 8–12 petals and grows on an evergreen shrub that reaches three feet in height and can last 7–10 years.

Madurai’s red laterite soil, rich in sulfur and a climate that is hot and humid for much of the year, produces a jasmine whose fragrance is bold, heady, and intense, untouched by nuance. It carries no citrusy tang, no woody or spicy warmth—only pure, unadulterated floral power. In the company of this jasmine, it is always a glorious day or the darkest night. It can take you to the peaks of amorous passion, or into the depths of devotion.

A personal connection

The sight and smell of jasmine fill me with pleasure. I can’t quite explain why—perhaps it’s the intensity that lodges itself permanently in the nostrils—but it evokes vivid, sunken memories. Having spent part of my childhood and all of my adolescence in Chennai, jasmine remains the scent of a warm place I call home. About 25 years ago, as a struggling, homesick journalist getting by on a shoestring in Delhi, I would always save at least ₹10 to buy a small string of jasmine as I walked back to my depressing tenement in the erstwhile Tamil ghetto of Munirka. I placed it around a tiny laminated picture of Ranganatha. By the time the stove—less efficient than a Bunsen burner—produced a hot one-pot meal, the flowers, accompanied by Ilaiyaraaja or Carnatic music, would take me on a journey to the banks of the Kaveri in Srirangam via Chennai. In those moments, life felt worth the struggle—and sometimes even beautiful.

“Such a small thing can be so iconic of so many bigger things: love, beauty, and purity. Of course, it is the favorite flower of Goddess Meenakshi, which was partly responsible for luring her husband, Shiva. But when a man meets his beloved, the most precious thing he can offer is a potlam—a small packet—of malli,” says Uma Kannan, a PhD in social and cultural anthropology who has spent years researching the flower and even written a book on it. Uma is married into one of the richest business families in South India, firmly rooted in Madurai. Her father-in-law, Karumuttu Thiagaraja Chettiar was a staunch nationalist during the British Raj. He founded swadeshi businesses spanning textile mills to banking, alongside educational institutions and philanthropies. Recognizing Uma’s love for jasmine, her husband Kannan Thiagarajan gifted her not a potlam, but a jasmine extraction business.

“He kept it a secret and told me only six or seven months before the factory became operational. He said it was for me to run, but he passed away in 2023 before it was inaugurated,” says Uma, clad in a pink silk sari at her Madurai family home with enough Chola bronze statues to make many Indian museums feel inadequate.

The French connection

While Madurai has been synonymous with jasmine for centuries, the French luxury perfume industry discovered it only recently. In 1989, Jean-Paul Guerlain, a fourth-generation master perfumer at the 200-year-old luxury firm (now owned by the LVMH Group), used Madurai jasmine to create a perfume called Samsara. Its success made every fragrance manufacturer seek out this precious sambac.

Thierry Wasser, the Swiss master perfumer and “nose” of Guerlain since 2008, has created perfumes like Dior’s Addict and Guerlain’s L’Homme Idéal. He was bowled over by the Madurai jasmine and now makes an annual visit to the region—not just to check on the quality of the flowers and the sustainability of the farmers, but also for inspiration.

“I wasn’t really acquainted with jasmine sambac much before. When I saw how people here used it—religious rituals, weddings, and celebrations—I suddenly understood the power of this flower. It stands for a celebration of love, friendship, brotherhood, and even your most secret hopes to the Gods,” says Wasser, waxing lyrical about Madurai jasmine, his dramatic Gallic gestures matching his words.

The variety of jasmine called grandiflorum, called jathi malli in Tamil, with buds that are spear-shaped and a pink tint, was grown in the southern France region around Grasse bordering Italy. Along with rose, it had been a staple in floral fragrances.

“Since Europe is cold, people used a lot of leather goods like gloves and jackets, and it doesn’t have a pleasing smell. The French found that they could mask the smell of leather by macerating it with the jasmine grandiflorum flowers readily available there. That’s when they realized they could make extractions from it,” says Raja Palaniswami.

When production of flowers in France became too expensive, the perfume companies looked elsewhere—initially to places closer to home such as Morocco and Egypt.

That’s when they discovered India grew grandiflorum in abundance. “But in India they got swept away by the power of jasmine sambac. Which is why it is the rock star among flowers today,” says Palaniswami, whose firm supplies jasmine and other floral extracts to luxury perfumers.

The jasmine season begins in March with the onset of summer and lasts until October. When the bushes fully mature in three years, farmers can harvest up to 4–6 tons of jasmine from an acre every season.

The early morning’s first harvest usually fetches farmers up to ₹450/kg while in the main city markets like Mattuthavani in Madurai, standing cheek-by-jowl to the primary bus stand, it can sell for ₹500–600/kg. But the harvesting continues through the day. Only the buds are plucked so that they can blossom en route without losing fragrance. The afternoon harvest finds its way to the numerous fragrance factories in the region. Companies like Palaniswami’s Jasmine Concrete pick it up at the farmgate at ₹300/kg. Although lower, it’s an insurance against price fluctuations in the open market.

Maria Velankanni, 48, is a farmer who looks many years younger, with a thick crop of hair, wearing a blue shirt and a matching lungi, in Kamalapuram, a village 50km from Madurai. Unmarried, he likes to think of his land and crops as family. “The jasmine grows well in our land because of the red soil and the heat. The heat gives it a unique smell. The Madurai jasmine is much thicker than other varieties. It can withstand long journeys to other parts of India and overseas even,” he says. Velankanni now prefers to sell to extraction companies for a fixed rate instead of making the daily dash to wholesale markets.

The fragrance extraction factories come to life after sundown. Tonnes of jasmine in wet jute sacks start arriving in mini-trucks by 8pm. The buds are dried and let bloom in large sheltered yards, spread out by a combination of feet and rakes. Once the moisture content is down, the flowers are loaded onto what seem like giant idli plates in a steamer and sent into the extractor. There they are subjected to hexane, a highly combustible, colorless hydrocarbon in liquid form, that can trap the aromatic molecules of jasmine. After the hexane is evaporated, a waxy substance called “concrete” remains. After this treatment, the “spent” jasmine flowers smell no different from tomato residue post pulp extraction.

The waxy concrete is then washed with alcohol to produce the liquid gold called jasmine absolute, which can be stored for decades. It is the most concentrated version of jasmine’s flavours. It takes 1,000 kg of jasmine to produce a litre of absolute. Raja Palaniswami’s factory in Madurai can produce 120 kilolitres of jasmine extract a day. A 100ml bottle of perfume needs as little as 1ml of this absolute. Lighter products like eau de toilette need even less. Applying a tiny drop of jasmine absolute directly on the skin might leave you with burns, not to mention, making you smell like a string of flowers for a few weeks.

However, jasmine farming has its unique challenges beyond the flower’s extremely perishable nature—its value and fragrance fall by the minute after it is harvested. Jasmine needs more pesticides than even vegetables. “We need to spray the field every four days and each spray costs ₹4,000,” says Ravindran, 27, an industrial engineer who works as a supervisor at a jasmine factory at night and helps his father Chinnaraman in the fields by day. Between 3pm and 5pm, the jasmine fields bring the deafening roar of diesel-powered pesticide sprayers; the sweetness of jasmine is doused by the acrid, metallic smell of engine fumes.

R Moorthy, 34, a tall sinewy farmer in Kamalapuram, gave up on jasmine some years ago. The high cost of cultivation was getting out of hand, and heavy doses of pesticides and fertilizers were wrecking his soil.

“A few years ago, I started attending programmes conducted by government and private jasmine factory agri-experts. There I discovered that it was possible to grow jasmine using natural inputs without chemicals. Now I grow it on a quarter acre in a fully natural way. The yields are fine, I get more money per kilo and more importantly, the soil has regained its health,” he says, showing his farm around wearing a pair of flip-flops, a printed blue shirt and an ochre veshti that matches the color of the land.

The lure of jasmine for the farmers, despite all the odds, is understandable. Unlike crops like rice or pulses, it brings valuable everyday income. Farmers such as Chinnaraman, for instance, can make a profit of up to ₹600,000 a year, especially with rising demand from perfume factories around.

Being part of an international supply chain brings some benefits.

“Customers and investors globally are asking companies like LVMH questions on traceability and sustainability of their products. There is the realization that if we don’t do things right today, there may not be a tomorrow,” says Palaniswami. Of the 2,500 farmers his company deals with directly, around 700 have been introduced to practices that minimize or even shun the use of chemicals.

For Thierry Wasser, a trained botanist, buying ingredients for his perfumes is a human adventure.

“You don’t buy jasmine, vetiver or rose from the market. You buy it from people. It’s a connection with life. The health of the people, the soil and biodiversity itself is of fundamental importance,” he says.

Meenakshi of Madurai may not disagree.

How polyhouse farming in Rajasthan’s desert is turning farmers into millionaires

Posted on February 24th, 2025

In the vast aridity of Rajasthan, winter brings relief from the scorching heat, but also an eerie stillness. Life here moves to the rhythm of sand and shrub.

On early mornings of late December, Jaipur, like any large city in north India, quivers in a silvery film of pollution. As you drive past the city’s last high-rises and elevated roads, the atmosphere is an emulsion of dust and smoke. Every movement lifts the earth into the air.

Here, dawn comes, but day doesn’t until noon. The dim, silver sun in an aluminum sky offers little heat or light. The fields are a naked beige after the monsoon groundnut crop has been dug up. The first green shoots of winter wheat and bajra have barely broken through the soil.

In a census of lifeforms here, trees would be an inconsequential minority. Among the trees, neem and khejri (also known as shami in most of north India and vanni, banni and jammi in the south) dominate. When I say dominate, they average two-or-three an acre.

The shami is considered a symbol of kshatriya valour. Legend says the Pandavas hid their weapons in a shami tree. Now, these trees, pruned and sheared for the season, resemble charred limbs raised in silent prayer. By summer, the khejri would yield nutritious pods called sangri used in the Rajasthani dish ker-sangri.

A wonder in the desert

Once we reach Gurha Kumawatan, a village 40km to the west of Jaipur, the transformation is startling. The fields are suddenly green and scurry with life. The raw sting of the air carries the red-wattled lapwings’ shrill and quirky ‘did-he-do-it’ call. Towering above the farmland, giant semi-circular enclosures—like Amazon warehouses—dot the landscape.

These are polyhouses, industrial-scale farms that allow farmers to produce up to ten times more food than in open fields. Using a technique called protected farming, they require only a fraction of the water, fertilizers, and chemicals needed in traditional agriculture even on poor soil and climate that’s oppressively extreme.

Farm as factory

In a modern factory work floor, machines, trained hands and processes are streamlined to mass-produce goods with high accuracy and repeatability. Farming, however, is ruled by unpredictable variables. A season’s toil can be undone by a few spells of unseasonal rain.

“Protected farming in polyhouses helps farmers run their fields like factories,” explains Balraj Singh, vice-chancellor of SKN Agriculture University, Jaipur, and one of India’s earliest scientists working on this technology. “They can control inputs like water and nutrients with precision, leading to vastly better yields. For instance, in northern India, tomatoes can typically be grown for just four to five months. In polyhouses, they thrive for nine or even more. Open-field tomato productivity is about 2.5 tons per hectare, but under protected cultivation, it jumps to 200 tons.”

Protected farming in polyhouses helps farmers run their fields like factories. They can control inputs like water and nutrients with precision, leading to vastly better yields. Open-field tomato productivity is about 2.5 tons per hectare, but under protected cultivation, it jumps to 200 tons.

Balraj Singh

Vice-Chancellor, SKN Agri University

The power of precision

Precision agriculture involves providing plants with exactly what they need, exactly when they need it. By delivering the right amount of water, nutrients, and crop protection directly to the roots, farmers can enhance productivity and maximize yields. When combined with protected farming, the results are truly remarkable.

In Gurha Kumawatan, you need to drill deeper than 150 metres to find groundwater, and even that is mostly saline. But it boasts India’s highest concentration of polyhouses, with nearly 1,200 acres under protected cultivation.

Most of the 500-odd farmers who own them are now millionaires, their combined turnover exceeding ₹250 crore. Unlike the average Indian farmer, who earns just over ₹10,000 a month, they live in massive mansions and drive around in snazzy cars. With staggering yields and wealth, they proudly call their region ‘mini-Israel.’

The story of this ‘wonder in the wasteland’ indeed has origins in Israel, with a pioneering farmer called Khemaram Choudhary in the lead, some fortuitous twists, relentless hard work and unlimited ambition.

The ‘mini-Israel’

Khemaram, 52, is a short man with pink cheeks, a bulbous nose and a ready smile. Dressed in loose white kurta-pyjama, an oatmeal Nehru-jacket, the traditional red bandhni safa with white speckles, and grey Skechers slip-ons, he has the reputation as a hustler who refuses to settle for the status quo. He is revered as the Bhishma Pitamaha of polyhouse farming—not just in Gurha Kumawatan, but across Rajasthan.

A chance visit to Israel in 2012 proved to be a turning point for Khemaram. A bright and curious student, he was forced to leave senior school due to family finances. As a teenager, he took on the responsibility of tending to his family’s three-acre farm, despite its meagre yields. Yet, his passion for innovation never faded—he eagerly attended local krishi melas, drawn to the promise of scientific farming methods and the possibility of better income.

By 2012, Khemaram had earned a reputation as a ‘progressive’ farmer, breaking regional records with his watermelon yields. Then, out of the blue, he received a call informing him that he had been selected for a 15-day tour of Israel to study modern farming techniques. “I didn’t even know a place called Israel existed. I thought it was a wrong call and hung up,” he recalls. His speech is a steady stream of heavy Jat accented Hindi that is unhindered by punctuation, pause or the need to breathe.

“Just days before receiving the call, I had stopped by Sanganer airport after delivering a truckload of watermelons to a trader, hoping to catch a glimpse of a plane taking off or landing. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine I’d be sitting in one myself,” he says.

Khemaram was part of a delegation led by Harjilal Burdak, Rajasthan’s then agriculture minister—an octogenarian and a staunch vegetarian like Khemaram himself. Their shared dietary preferences brought them closer during the trip, giving Khemaram front-row access to every high-tech farming demonstration.

When Israeli farmers and scientists claimed it was possible to earn ₹15-20 lakh from just an acre of arid land, Khemaram was convinced it was an elaborate con job.

After all, Israel receives just 508mm of annual rainfall, barely different from Jaipur district’s 565mm, where Gurha Kumawatan lies in one of its driest parts.

“Look, I was a good, hardworking farmer. I had never made a profit of more than ₹1.5 lakh, nor had I heard of any farmer in India making much more. And you know what? The Israelis gave us water that was processed from the gutter! If mantri ji had known, I swear he’d have flown in a plane full of Bisleri water from India for the trip,” he recalls with a chuckle.

While most of the touring party comprised political freeloaders and factotums, Rajasthan officials were eager to prove the costly trip was worthwhile. They urged Khemaram to convert 1,000 square meters of his land into a protected polyhouse farm, covering all expenses.

To fob them off, he made a bold counteroffer—he’d do it if they funded 4,000 square meters (nearly an acre). A week later, approval arrived.

State subsidy and super profits

At the time, setting up a polyhouse with necessary equipment cost ₹40 lakh. The government offered ₹30 lakh as subsidy, arranged low-interest loans from state banks, and provided full technical support from the local agricultural university.

When Khemaram began growing hybrid, seedless cucumbers (now commonly called English cucumbers in India) inside the polyhouse, his family, including his father, thought he was being duped.

As the structure rose, the village consensus was clear: Khemaram was building a “palace of dreams” that would only end up in debt and disaster.

“My very first cucumber crop earned me ₹13.6 lakh in just three months. I could start harvesting within a month. It was nothing short of a miracle,” he recalls.

The seedless hybrid cucumber grown in the polyhouses has a smooth, waxy, deep green skin, and is sweeter than traditional Indian varieties. When Khemaram took his first cucumber harvest to Jaipur’s Muhana mandi, traders wouldn’t buy it because they hadn’t seen it. “They thought I was massaging the cucumbers with oil to make them shiny and sweet. In the first week, I gave everybody in the market free samples,” he recalls.

Today, after less than 15 years of polyhouse farming, Khemaram is a multi-millionaire. His annual profits exceed ₹2 crore. He spent ₹1 crore each on the weddings of his two daughters to wealthy city grooms, owns multiple plots and villas in Jaipur’s elite enclaves, and has no worries about his 27-year-old son needing a job outside agriculture.

My very first cucumber crop earned me ₹13.6 lakh in just three months. I could start harvesting within a month. It was nothing short of a miracle.

Khemaram Choudhary, Farmer, Gurha Kumawatan

The Roman past

The practice of growing crops, especially fruits and vegetables, in controlled environments like polyhouses dates back centuries. Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder documented proto-greenhouses used in 1st century AD to cultivate melons year-round in enclosed structures called specularia made of translucent stone sheets. These were built to ensure Emperor Tiberius had a steady supply of his favourite fruit every day of the year.

Following World War II, as plastic became more accessible, European farmers began covering their fields in winter, pioneering modern protected farming techniques that would later have a big impact on global agriculture.

Protection from debt

Khemaram’s near-instant success not only inspired neighbouring farmers to adopt polyhouse farming but also reversed the trend of young people migrating to cities in search of well-paying jobs.

“Earlier, people here mocked me, saying I had more debt than hair on my head. Now, farmers from across the country come to learn from me, and the same banks that once shooed me away now line up outside my gate, asking for business and customer referrals,” Khemaram says with a grin, seated in the spacious ante-room of his bungalow—a space that doubles as a gym, complete with a treadmill and oversized boom boxes.

Thanks to his polyhouse earnings, 72-year-old Gangaram Nitharwal now owns two petrol pumps and multiple mansions, including one perched atop a hillock, offering him a panoramic view of Gurha Kumawatan.

Gangaram’s rugged face, leathery skin, and stubby, calloused fingers tell the story of a life spent in the fields. Seated in his sprawling lounge—its three sides encased in glass—he reclines on a rustic cane throne, wearing a more vibrant safa than Khemaram, surrounded by charpoys draped in plush candy-coloured cushions. There are ornate hookahs, and air-conditioning too. His voice is low and measured, carrying a quiet air of authority. After all, the eldest of his two sons is now the village sarpanch. A white Toyota Fortuner is always at Gangaram’s disposal. “I make more money from polyhouse farming than my two petrol pumps. Can you believe it,” he asks, tousling the newly acquired white poodle that hasn’t been assigned a name yet.

Prosperity unlimited

The economics of polyhouse farming are compelling.

“Two years after I began polyhouse farming, people in the village thought I was either lying about my income or had a currency-printing machine,” says Khemaram. Soon enough, they all followed his lead.

Setting up a 4,000-square-metre polyhouse with drip irrigation, foggers, and sprinklers to regulate temperature and humidity costs over ₹50 lakh. Most large polyhouses are built alongside ponds, roughly the size of a tennis court, to harvest rainwater. Water usage is so minimal that a single monsoon’s rainfall can last nearly a year.

A slew of central and state government schemes offer subsidies covering up to 90% of the capital cost.

Enclosures used for protected farming can take many forms. The low-tech greenhouses are erected on beams of bamboo or local wood. The plastic shade helps to protect against heavy rain or heat.

The polyhouses used by the farmers of Gurha Kumawatan fall into the medium-to-high-tech category. Semi-translucent 200-micron polyethylene sheets are used to cover grids of galvanized iron pipes that act as the skeleton for polyhouses. The sheets can last up to 5-7 years. While all the polyhouses have drip irrigation, foggers, and sprinklers for humidity and temperature control, some of the more expensive, high-tech polyhouses have IoT devices and complete automation.

A happy harvest

An acre of polyhouse farming yields, on average, 100 tons of cucumbers annually, significantly higher than the 20-30 tons per acre typical of traditional open-field cucumber farming. Prices can soar to ₹35 per kilogram when demand spikes, but most farmers prefer fixed-price, long-term contracts with buyers. The current going rate is around ₹25 per kilogram, translating to a revenue of ₹25 lakh per acre.

Polyhouse farmers typically employ resident worker families, known as seeri, who receive 25% of the total income. After accounting for their wages and roughly ₹5 lakh in input costs, farmers can net a profit of ₹12 to 15 lakh per year from an acre.

Though yellow and red bell peppers yield only 35 tons per acre, far less than cucumbers, their income potential is higher since prices can climb to ₹250 per kilogram.

“It is easier to get labour for polyhouses because they do not have to work in extreme heat. The 25% revenue-sharing system is a partnership, giving them an incentive to make the crop a success,” explains Khemaram.

While floriculture in glasshouses is not new to India, serious efforts toward protected food crop cultivation began in 1998 as part of an Indo-Israel collaboration. Israel, an agricultural technology superpower, has pioneered innovations that allow its farmers to grow tropical fruits like avocados, oranges, and mangoes even in the arid Negev Desert.

No-entry for nature?

Currently, protected farming of the kind practiced by Gurha Kumawatan farmers has a significant limitation. Only those plants that are self-pollinating such as tomato, chilli, seedless cucumber, brinjal, and strawberries can be grown.

Self-pollinating plants have both male and female reproductive parts in the same flower, such as tomatoes, chillies, seedless cucumbers, and strawberries, so the pollen from the male part (anther) can fertilize the female part (stigma) within the same flower. Cross-pollinating plants need help from nature to produce fruit.

In the controlled environment of polyhouses, natural pollinators such as birds and bees are absent.

In Europe and countries with a colder climate, bumblebees are used for pollination in polyhouses. India does not allow the use of bumblebees because they might affect local biodiversity. However, scientists in India are working on using a stingless native bee species specifically for protected cultivation.

“In the initial years, we realized Israeli technology did not work all that well. India has a diverse climate, and Indian farmers cannot afford a system that requires a lot of electricity,” says Balraj Singh, clad in a navy windowpane check blazer and white chinos.

To address this, Indian scientists adapted the technology to function with minimal power, incorporating off-grid solutions like solar panels. Modifications were also made to suit regional climatic conditions and farming practices.

China leads the world in protected cultivation, with nearly 3.5 million hectares under cover, largely due to government support, technological advancements, and a focus on food security. In contrast, India has only around 2 lakh hectares, as the concept has yet to gain widespread adoption.

An equal opportunity

Many smallholder farmers are hesitant due to the high initial investment, often perceiving it as a practice suited only for the wealthy.

Not many of Gurha Kumawatan’s farmers had the means either.

Babulal Jat, 38, is a lean, gangly man with large ears and sunken cheeks. He spent most of his life working as a seeri. His land, just over half-an-acre, could barely support his family of three children. With the money he had saved as a seeri, along with government grants, he switched to polyhouse farming five years ago.

A few months ago, his family moved into a new two-story house with shiny granite flooring and a spacious portico. The house cost ₹24 lakh to build.

“Two of my children are now in college. The money I’ve made has elevated my stature and earned me the respect of wealthier farmers,” he says.

Mahendar Kalwania, 28, has just had a daughter. Extended family and friends have gathered in the lawns of his massive two-storey mansion to celebrate over a simple feast comprising a sweet khichri made of daliya and red gram, poori and dal, and hot pakoras.

Dressed in a black gilet and checked navy shirt, Mahendar, a polite yet confident man, had always dreamed of joining Rajasthan’s civil services. It’s a common aspiration among the youth in this region. However, soon after he completed his master’s degree in commerce, his father passed away, and family responsibilities fell on his shoulders.

Taking up a job in the city was not an option, as he needed to stay close to home to support his family and manage their land. A few years ago, he decided to try cultivating cucumbers in a single polyhouse. Encouraged by the success of his initial efforts, he expanded the operations significantly.

Now, his family owns 24 polyhouses, and Mahendar manages them all. “Look, our annual income is Rs 2.5-3 crore a year. I have four cars, this bungalow, and a lovely daughter now. I don’t think it makes any sense for me to leave this and work a city job,” he says.

Strength in unity

The farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, buoyed by their success, have established a farmer producer company (FPC) called Agriglow. An FPC is a social enterprise that blends elements of a cooperative, like Amul, with a private limited company. It can be formed when 10 or more farmers in a region come together, with ownership and management retained by the farmers themselves. By uniting under an FPC, farmers can access larger markets, negotiate better prices, and reduce their reliance on middlemen—enhancing their incomes and ensuring greater economic sustainability.

At the helm of Agriglow is 87-year-old Devendra Raj Mehta, a retired IAS officer with a distinguished career. Mehta served as one of the longest-tenured chairmen of India’s stock market regulator, SEBI, and as a deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India. He also founded the NGO Jaipur Foot, which has provided artificial limbs to more than two million people with disabilities.

Driven by a passion for modern farming, Mehta and his daughter-in-law—a PhD in microbiology—ventured into polyhouse farming a few years ago, inspired by Khemaram’s success.

“What distinguishes this area is that farmers have become very modern. Farming is also a means of earning a living. Naturally, they want more income. That’s not greed, but genuine aspiration. They’ve realized that by adopting science and technology, they can increase their yields. They are now more proactive—fighting for their rights, engaging with the government, and making informed suggestions. United you stand, more powerful you are,” he says.

Under Mehta’s guidance, the FPC aims to secure greater government subsidies for polyhouse farming and explore larger national and international markets. The farmers of Gurha Kumawatan are now planning to sell their produce directly to urban consumers through e-commerce platforms and explore export opportunities to markets like Dubai.

According to Balraj Singh of SKN University, peri-urban clusters like Gurha Kumawatan—known for producing high-value horticultural crops—are best positioned for success. “These areas are close to big cities where restaurants and fast-food chains need high-quality produce like bell peppers on a large and consistent scale. Additionally, the proximity to highways allows their produce to reach ports like Mundra and Mumbai within 24 hours,” he explains.

Pan-India possibilities

If farmers in the desert can become millionaires, can this model be replicated elsewhere?

“It absolutely can,” says Khemaram. “Farmers with better soil and water conditions can achieve even greater success than us. It requires just two things: hard work—you have to be fully committed and not treat technology like a magic wand—and courage to let go of fear. Protected farming and polyhouse cultivation work. Come visit us; we’re happy to share our experiences. There’s no other way forward for farmers seeking success.”

Watch | India’s Dairy Dilemma: From White Revolution to Warnings of Decline

Posted on January 16th, 2025

The dairy industry has long been a pillar of Indian agriculture, earning its status as a standout success story. From the days of milk shortages at independence to becoming the world’s largest producer of milk, India owes much of this transformation to the White Revolution led by Verghese Kurien. However, as India celebrates 50 years of this achievement, the sector faces a raft of challenges that could reverse its hard-earned gains.

A legacy of success

At independence in 1947, India’s dairy sector was unorganized, with low productivity and insufficient supply. Most milk came from buffaloes, as indigenous cows were primarily used for draught purposes. By the 1970s, the White Revolution, spearheaded by the establishment of Amul and the National Dairy Development Board, ushered in a paradigm shift. Cooperative models linked millions of farmers to chilling centres and urban markets, ensuring consistent supply despite milk’s perishability. Today, milk availability has soared to approximately 420 grams per person per day, a stark contrast to the deficit years. Yet, the industry’s productivity remains well below global standards. Indian cattle yield an average of 3–4 litres of milk daily, compared to the 20 litres or more achieved by European breeds.

The slowdown in growth

Recent data underscores a worrying trend: milk production growth has halved from 6% annually to just 3.78%. Experts attribute this decline to a combination of outdated breeding programs, poor farm management, inadequate farmer education, and over-reliance on subsidies. Shashi Kumar, founder and CEO of Akshayakalpa Organic, highlights systemic issues. “We have doubled our cattle population since 1950 which has contributed to the increase in production. Most farmers lack access to modern breeding or feeding practices, perpetuating inefficiencies.”

The cost of cheap milk

India’s cooperatives, like Amul and Nandini, have been instrumental in making milk affordable. However, low consumer prices come at a cost. Farmers often sell milk at or below the cost of production.

In Karnataka, the cooperatives pay farmers ₹35 a litre that includes a ₹5 incentive the government pays from taxpayer money. Shashi Kumar explains, “Most dairy farming is sustained by unpaid family labor and unaccounted costs. It is impossible to produce a litre of milk below ₹35. So in effect, no dairy farmer makes any money.”

Artificially low prices also hinder private sector growth and innovation. Companies like Hatsun, one of the largest publicly traded dairy companies, and Akshayakalpa, which operate outside the cooperative system, invest heavily in quality and farmer education but struggle to compete with subsidized rates.

Despite this, demand for premium, organic milk is growing, with Akshayakalpa’s products commanding prices up to two-to-three times the market average.

Global quality concerns

India’s milk quality issues extend beyond domestic markets. Indian dairy products consistently fail to meet global phytosanitary standards, limiting export opportunities. Poor animal nutrition, unhygienic milking practices, and inadequate cold chain infrastructure contribute to substandard milk quality. “We may be the largest producer, but not many countries want to even touch our products,” says Shashi Kumar. The Way Forward

To prevent a potential crisis, Shashi Kumar stresses the need for systemic reforms:

1. Modernizing Breeding Programs: Current breeding strategies, including crossbreeding indigenous cows with exotic breeds, must be better managed. Investment in indigenous breed improvement, as seen in Brazil’s success with Indian-origin cattle, is crucial.

2. Farmer Education and Support: Comprehensive extension programs can teach farmers sustainable feeding, breeding, and farm management practices. For instance, Akshayakalpa employs one extension officer for every four farmers to ensure adherence to quality protocols.

3. Fair Pricing and Reduced Subsidy Dependence: Establishing a fair price mechanism for milk that reflects actual production costs will empower farmers and attract private investment.

4. Focus on Quality: The industry must prioritize antibiotic-free, toxin-free milk production to tap into premium markets and improve domestic health outcomes.

5. Infrastructure Development: Expanding cold storage and chilling infrastructure will reduce post-production losses and improve milk quality. India’s dairy sector stands at a crossroads. The lessons of the White Revolution prove that with the right vision and commitment, transformative change is possible. However, the path forward requires embracing quality, sustainability, and farmer empowerment. Without these measures, India risks squandering one of its most remarkable agricultural achievements. The stakes are high—not just for farmers, but for millions of consumers and the nation’s food security.

From economics graduate to farming trailblazer: Anushka Jaiswal’s inspiring journey

Posted on January 16th, 2025

When Anushka Jaiswal, 28, was the president of the placement cell during her final year at Delhi’s prestigious Hindu College, she helped nearly all her classmates land jobs. Yet, she wasn’t keen on following suit herself.

Call it clarity of mind or youthful certitude, Anushka was pretty sure what she didn’t want. The monotony of sitting behind a desk, confined to a traditional workplace, topped her list.

Upon returning to Lucknow after graduation, still uncertain about her career path, she found herself captivated by her mother’s terrace garden. On a small rooftop, her mother had managed to grow a variety of vegetables—tomatoes, gourds, and more.

“I realized I really enjoyed this work and would never get bored of it. That’s when the idea struck me to turn my hobby into a profession,” she recalls.

Embracing innovation

Anushka’s family had a history of farming, which sparked her desire to arm herself with modern, scientific knowledge. She enrolled at the Institute of Horticulture Technology in Greater Noida, where she learned about hydroponics and protected cultivation. These techniques offer a sustainable and profitable alternative to traditional agriculture.

Protected cultivation involves creating a controlled farming environment. A semi-cylindrical indoor structure called a polyhouse is built using iron grids and translucent plastic sheets. Polyhouses regulate temperature and humidity, ensuring better land efficiency and water savings via drip irrigation. The technique eliminates weather risks and allows for year-round vegetable production.

Hydroponics, by contrast, removes soil from the equation, using mediums like coco peat or chips instead.

“Traditional farming isn’t the future,” Anushka asserts. Thanks to protected cultivation, her farm now yields up to 30 tons of seedless cucumbers and bell peppers per acre, compared to the 4-6 tons produced by traditional methods. This approach conserves resources—water, quality soil, fertilizers, and pesticides—while addressing climate challenges and contributing to global food security.

Overcoming challenges

Anushka’s path hasn’t been without obstacles. Lacking ancestral land and struggling to secure investment, she encountered significant barriers. Gender stereotypes added another layer of difficulty. Family and friends she approached for loans questioned whether marriage would pull her away from the business. But Anushka’s determination set her apart. “This is my bread and butter. I’m not leaving it behind,” she says.

Polyhouse farming is an expensive venture, with costs reaching up to Rs 50 lakh for one acre of structure. However, governments offer loans and subsidies covering up to 80% of costs. The high yields typically allow farmers to recover their investment within a year.

Anushka started in 2020, cultivating cucumber on a small piece of leased land. The first harvest, just three months later, was promising—but the pandemic meant prices were lower than expected. However, as conditions improved later that year, she earned over ₹20 lakh from just one acre. To put it in perspective, an average Indian farmer cultivating traditional crops like wheat or paddy on one acre typically earns only ₹1 lakh. Today, her operations span six acres with an annual turnover of ₹80 lakh.

Empowering women in agriculture

Anushka employs 25 women farmers, emphasizing their unique ability to handle delicate plants with care. “Women are more tender with plants and monitor them closely for issues,” she explains. This inclusive approach not only boosts productivity but also empowers women in an industry where they are often underrepresented.

Building trust with her workers and investors wasn’t easy, but Anushka’s results speak for themselves. Shahzade Ali, Anushka’s manager, recalls, “I used to wear ragged clothes, toil under the sun, and barely save anything as a traditional farmer. After joining Anushka didi’s farm, my lifestyle and financial circumstances have drastically improved.” He gestures toward his new bright orange jacket and muffler, a symbol of his newfound stability.

The role of government and the path ahead

While subsidies and programs under the Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (MIDH) have supported Anushka’s efforts, she stresses the need for more responsive policies. “Government subsidies are based on outdated rates, which don’t account for rising costs,” she says. Anushka advocates for better farmer training and resources to make sustainable farming methods, like protected cultivation, accessible to all.

Inspiring a community

Anushka’s work has inspired traditional farmers in her region to consider adopting sustainable methods. “You cannot grow alone,” she says, emphasizing the importance of mutual growth. “My investors, workers, and village are all growing with me.”

Her journey is a testament to what determination and innovation can achieve, even in the face of societal expectations and logistical hurdles. Anushka Jaiswal is not just growing crops—she’s cultivating a brighter, more sustainable future for Indian farming.

What is the Agri Stack?

Posted on July 23rd, 2024

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi, or PM Kisan scheme, is the largest welfare programme for farmers in India. All landholding farmers, irrespective of the size of their holding, get an income support of Rs 6,000 per year – transferred in three equal instalments – into their bank accounts.

Since its introduction in February 2019, the union government has transferred funds to the tune of Rs 2.81 lakh crore ($33.58 billion) through direct benefit transfer (DBT) to 110 million farmers and it costs the government Rs 60,000 crore annually.

PM Kisan is undoubtedly the flagship government scheme to act as a salve for India’s farmers under chronic economic distress.

After all, nearly 75% of Indian farmers own less than one hectare of land – barely the size of a cricket field. The average monthly income of an Indian farming household, according to the latest government data, is Rs 10,218. That roughly translates to Rs 340 a day, at par with daily wages unskilled labourers in many states get under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA).

Data deficiency

But the design of PM Kisan raises some fundamental questions. Is the government accurately counting the number of landholding farmers? While 110 million farmers benefit from the scheme, the government’s own estimate of farmers vary wildly. The 2015-16 Agriculture Census pegs the number at 146.45 million. The National Statistical Office (NSO) claims there are about 90 million agriculture households in India.

In short, we simply do not know how many farmers there are or indeed how many of them own a piece of farmland.

While the Indian agri sector employs roughly half the country’s workforce and accounts for less than 20% of the economy, there is very little or reliable statistics for policymakers to go by. For instance, state and central governments have patchy information about say the farmers’ intention of sowing onions or tomatoes at the start of a season. The wild price swings of such key commodities is partly a result of poor understanding of the supply.

In a primitive supply-chain market like India, farmers often choose to grow a lot more of a crop if its prices were high in the past season. If millions of farmers decided to grow tomatoes over brinjal because tomato prices were sky high, there would be a glut of tomatoes in the markets, and inevitably the prices would crash.

The absence of data at every part of the farm-to-plate chain keeps this sector inefficient.

The kisan JAM

This is where Agri Stack may help.

Agri Stack is a public-private partnership that’s trying to create a digital foundation to improve agriculture in India and enable better outcomes for the farmers by using data and digital services.

Much like the IndiaStack based on Jan Dhan accounts (zero balance universal bank accounts), Aadhaar card based identification and mobile connectivity – often called the JAM trinity – helped in financial inclusion and targeted delivery of welfare schemes, the government hopes that the Agri Stack can do the same for India’s farmers.

Its first task is to build a real-time digital farmers registry and digitized village maps just to be able to know the number of farm holdings.

In computer parlance, a “stack” refers to a set of software infrastructure, tools and applications that software developers can use to build and innovate. The Agri Stack has been envisaged as a set of open digital infrastructure and tools that government, industry, and start-ups can use to build solutions for agriculture.

In the 2023 Union Budget, the government announced the implementation of this digital reform to bring greater transparency and accountability in agriculture. “This (digital public infrastructure for agriculture) will enable inclusive, farmer-centric solutions through relevant information services for crop planning and health, improved access to farm inputs, credit, and insurance, help for crop estimation, market intelligence, and support for growth of agri-tech industry and start-ups,” said Nirmala Sitharaman, Union Finance Minister in her 2023 Budget speech.

Before we examine the progress of Agri Stack in its first year, it is important to analyze the three reasons why it is necessary for India.

1. Better targeting of subsidies

In 2022-23, agriculture accounted for 2.8% of India’s Union Budget. The Budgetary Expenditure towards farmers’ welfare was Rs 1.25 lakh-crore, 77% of which is allocated for welfare schemes like PM Kisan, according to this PRS Legislative Research analysis.

According to the Doubling Farmers’ Income (DFI) Committee, headed by Ashok Dalwai, subsidies in 2015-16 on inputs like fertilizers, water, power, and procurements linked to minimum support price (MSP) were Rs 243,811 crore. The corresponding figure in 1990-91 was Rs 12,158 crore – the subsidies on agricultural inputs had grown 20 times in 25 years.

Given the size of the subsidies, the Committee recommended that farmers’ welfare needs to be measured based on the following indicators: both absolute and relative average income; availability and accessibility to social security system – education, health, etc.; and facilitating the farmer in moving up the need hierarchy beyond social hierarchy.

Once the farmers’ income and input management (on fertilizers, water, etc.) is established in a dynamic digital database, the subsidies and welfare programmes can be better targeted at those who actually need it. This is what Sitharaman alluded to in the Budget speech when she spells out relevant information services for crop planning and health, and improved access to farm inputs.

Already, the Economic Survey 2023-24, released on July 22, 2024, states the government’s ambitious plan to distribute the fertilizer subsidy using Agri Stack. “This will ensure that subsidized fertilizers are sold to only those identified as farmers or authorized by the farmer, and the quantity of subsidized fertilizer is fixed based on parameters such as land ownership and prominent crops of the district (comprising at least 70% of sown area in a season),” according to the latest Economic Survey. In 2023-24, the union government budgeted Rs 1.75 lakh-crore for fertilizer subsidies, which was 66% greater than the budget estimates in the previous fiscal year.

2. Better access to farm credit

Based on ground experience, companies like Samunnati have seen a spate of issues that farmers and banks face with respect to agricultural finance. Samunnati works with farmer-producer organizations (FPO), a collective of ten or more farmers that can be run as a private sector company, to help them source inputs at lower costs, find the best markets for their produce, and get financing from banks and non-banking financial institutions.

“Almost 50% of the time, a loan gets rejected for a valid farmer and a valid land because the bank cannot establish ownership in the documentation,” says Raj Vallabhaneni, former CTO of Samunnati, and Founder-CEO of Kalgudi Digital, a software start-up in agriculture. Banks find it hard to gauge the farmer’s repayment record, his farmland, what crops he grows, and their sales potential. In this context, a farmers database will smoothen out lending services in agriculture for banking, financial services and insurance sectors.

Further, large procurers of agri produce will find it easier to do contract farming, Vallabhaneni notes. Indian agriculture is dominated by farmers with small landholdings, which makes it difficult for the private sector in contract farming to assess which farmer owns what tract of land. With the database, the time taken for transactions can be reduced to the mutual benefit of the farmer and agri-foods company that wants to do contract farming.

Without the database, a large number of farmers don’t get access to formal credit, leaving them with the option of turning to moneylenders or the black/ cash economy. This is also why most farmers are excluded from the welfare schemes – they don’t have updated land records to establish their ownership of a farm. And by definition, a farmer in India must own a piece of land. It leads us to the third reason for the farmers’ database: identity.

3. A better definition of ‘farmer’

There are various combinations of problems related to information about a farmer. For one, there is no standard definition, except that a farmer is a farmer if he or she owns a piece of land. The open-endedness of this definition has led to a maze of incomplete information about farmers, which has been further complicated by migration.

“We have a peculiar situation where we have more moonlighting farmers than full-time farmers,” says Venky Ramachandran, an agritech analyst who runs Agribusiness Matters, a newsletter. The average profile of a farmer could be somebody who is working in another part of the country as a migrant labourer or a cab driver, Ramachandran explains. “He would depend on his family to take care of the farm, returning during the season to become part of the activity,” he adds.

Who exactly is a farmer?

Another, crueller aspect of identity in agriculture concerns the cultivator on India’s farms – a tenant farmer or contract farmer who doesn’t own land, but works on farms through the year. Currently, such cultivators – estimated to be more than 100 million people – borrow money from the informal economy to purchase inputs and work as full-time farmers. Yet, they are not recognized by the laws of India.

While the Agri Stack cannot solve the problem, the union and state governments can through legislative changes. If and when that happens, cultivators can apply for welfare schemes, working capital and credit based on their credentials in the farmers registry.

According to Rajeev Chawla, strategic advisor and chief knowledge officer in the union ministry of agriculture and farmer welfare: India has roughly 170-180 million land owning farmers with approximately 850 million parcels of land. So, each farmer owns on average five parcels of land. “If you talk about landless farmers, cultivators and tenants — India has 100 million,” he added, at a fintech event in Mumbai in September 2023.

In 2018, the DFI Committee too called for a legislative review to include cultivators or tenanted farmers.

The DFI Committee points out that a large number of government schemes and programmes become eligible to farmers based on their land ownership certificate. This tends to exclude the landless cultivator, fishermen, nomadic farmers and livestock rearers . To make the condition of farmers better, “they also must be recognized as farmers and rendered eligible to all the benefits under various schemes, programmes, missions, as also institutional credit and relief measures,” the Committee notes.

The question is, can the Agri Stack do to agriculture what Aadhaar has done for the direct benefit transfer in the past decade? To answer that, let’s first understand what the Agri Stack will look like.

Contours of Agri Stack

In the first phase of Agri Stack, the union government is working with 12 state governments to build the farmers registry. The states are Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Assam, Odisha, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh. Most recently, Chhattisgarh has begun to digitize the information related to farmers and landholdings for Agri Stack.

The governments have undertaken to create a Farmers Registry for their respective states. It entails granting farmers of each state a Unified Farmers Service Interface (UFSI) number.

The information farmers share (backed by their land records) will help establish each of their details such as personal particulars (name, gender, age), details related to land and location, crop, health of soil, and benefits they are availing. Accordingly, a Unified Farmers Service Interface (UFSI) number/ code will be assigned to map each farmer on the farmers registry.

The farmers registry system will help government or bank officials determine the identity of farmers, the size and location of their holdings, and what crops they are growing where.

The core registries of Agri Stack will thus be the farmer registry, the geo-referenced village maps, and the crops sown registry.

“In a couple of years, Agri Stack can do to farmers what Aadhaar did for beneficiaries (of the direct benefit transfer schemes),” Chawla told entrepreneurs at the fintech fest in Mumbai in September 2023.

The Aadhaar Way

The first unique ID or Aadhaar ID was generated in 2010, and the Unique Identity Authority of India (UIDAI) has covered more than 97% of residents in India over 14 years.

In 2012, the union government led by the Unified Progressive Alliance introduced the direct benefit transfer. It aimed to transfer benefits and subsidies directly into the bank or postal accounts of beneficiaries. Citizens were incentivized to link their bank accounts with their Aadhaar IDs because it could smoothen the authentication process. For government officials, Aadhaar-seeded bank accounts meant they could accurately target beneficiaries with the subsidies they were entitled to.

At the time, the problem facing India was that banks hadn’t gone deep enough into rural India, even as Aadhaar enrolment was growing at a faster clip. To solve this, the union government introduced the Jan Dhan Yojana in 2014 to ensure every household gets access to a bank account, a debit card, and up to Rs 10,000 overdraft facility from the banks.

The Jan Dhan Yojana is the largest financial inclusion programme in the world. It also completed the two elements required for electronic delivery of subsidies through DBT. One, Aadhaar to identify a beneficiary correctly, and, two, the bank account to ensure the money reaches the intended recipient. “Once the Aadhaar number is added to the database of all social welfare recipients, the government can accurately identify these individuals,” wrote Nandan Nilekani, referring to the electronic payments system in DBT in Rebooting India (2015).

“On the other side, linking a person’s bank account with their Aadhaar number makes it possible to reliably verify the identity of the account holder. Aadhaar now serves as a link between the government and the people, making it easy both for the authorities to transfer payments to the correct individual’s bank account, as well as for people to easily withdraw money using Aadhaar to authenticate their identity.”

For the Agri Stack, what is needed now is to establish the core registries, just as Aadhaar has done.

In the Union Budget 2024-25, the government announced a time frame of three years for coverage of all farmers and their lands. To achieve this, it has launched a digital crop survey in the kharif season in 400 districts. “The details of 6 crore farmers and their lands will be brought into the farmers’ and lands’ registries,” Sitharaman said on Tuesday.

Already, the PM KISAN scheme has helped onboard 110 million farmers. “These beneficiaries can enroll for their farmer ID – the process is similar to how citizens apply for their Aadhaar number,” said a source in the agriculture ministry, who requested anonymity. The Agri Stack will then automatically link the farmer ID against the farmer’s name in the PM KISAN database.

“If the central government digitises the land records successfully, they would have solved 80% of the problem,” says Krishna Kumar, Co-founder and CEO of Cropin Technology Solutions, a farm intelligence start-up. “You are then able to provide advisory services, and bring financial inclusion.” But this in itself is a huge ask. “When you roll out a digital mission of this scale for farmers, there are many complexities and moving parts,” he adds.

For instance, land boundaries and crops history have to be established, and the data resolution harmonized across states, right down to the district and village levels. This brings in the complexities. For instance, while the land is constant, its ownership and crops sowing patterns change. So, the farm and crops sown registries will need to be live, and constantly updated.

The good news is the government hasn’t taken up such a massive and multi-year project alone. With Agri Stack’s open framework, the private sector has a role to play in the design and implementation from the get-go.

“Even if the central government builds out a national crops dashboard as a base platform, it can share that infrastructure with state governments to build on top of it,” Kumar says. “It can then scientifically build budgetary estimates based on that data.”

For financial credit to farmers, banks need three pieces of information about the farmer: whether a land belongs to a farmer or not, his repayment record, and his crop outlook.

The harder piece of universal banking has been solved for financial inclusion thanks to the Jan Dhan scheme. So, the Agri Stack is well placed to ensure the targeted delivery of agriculture input subsidies, and even become the de facto database because of which farmers can get working capital loans or long-term credit.

Without Aadhaar to ensure farmers’ identity, and the Jan Dhan scheme for Aadhaar seeding of the bank accounts, the government wouldn’t have been in this position of strength. But in terms of sheer impact on the economy, the Agri Stack is perhaps an even more important digital mission than Aadhaar – it will formalize Indian agriculture.

From Udaipur to Okinawa riding on orange peel

Posted on May 5th, 2024

The story of twenty-five -year-old Narayan Lal Gurjar might not be out of place in Bollywood.

The playful experiments he conducted in his father’s small farm as a teenager in Kerdi, a village of 300 with 40 homes in Rajsamand district in southern Rajasthan, is the foundation for his patents and the agriscience startup incubated by Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) that has attracted investments from well-known Japanese venture capital firms such as Beyond Next Ventures and MTG.

And all this before he turned 23.

Gurjar’s firm EF Polymer (EF stands for eco-friendly) headquartered in Okinawa with manufacturing plants in Udaipur makes super absorbent polymers (SAP) from orange and banana peel that has the potential to help millions of small farmers in arid and water scarce regions across the world harvest better yields.

Suck it up

Now, SAPs aren’t new and neither is their use in agriculture. As the name suggests, SAPs are crystalline resembling rock salt or monosodium glutamate used in kitchens that can absorb and retain water a thousand times their weight. Besides industrial applications, SAPs are commonly used in diapers, sanitary pads and ice-packs.