Drone duo that heals crops with pictures from the sky

Posted on March 28th, 2024

Amandeep Panwar, 30, and Rishabh Choudhary, 31, first set foot on a farm in 2015. As students in an aeronautical engineering graduate course at a Lucknow college, farms in a village nearby offered the vast open spaces to fly a drone for their final year project. The friendship they struck up in college has resulted in BharatRohan, a startup with revenue of nearly Rs 20 crore in the frontier space of precision agriculture technology.

Founded in 2016, immediately after Panwar and Choudhary graduated, BharatRohan uses hyperspectral imaging, one of the most advanced remote sensing tools to capture warning signals about pest attacks, disease outbreaks and nutrition deficiency in crops at a very early and actionable stage. “Remedial action at this early stage helps farmers eliminate crop losses. It can be one of the most important innovations in agricultural early warning systems. The potential is humungous,” says Kondapi Srinivas, principal scientist at Indian Council of Agriculture Research’s (ICAR) National Academy of Agricultural Research Management (NAARM) in Hyderabad that incubated the start-up.

The power of precision

Every year India loses in excess of 15% of its farm output worth about $40 billion to diseases, pests and climate related crop stress.

BharatRohan’s drones are fitted with hyperspectral imaging (HSI) cameras that film the farmland every week to ten days. The technology and the firm’s proprietary algorithms can decipher the miniscule colour changes occurring in the plants due to different biochemical changes. For instance, a pomegranate plant infested with bacterial blight develops red-brown spots on the leaves. To a naked eye, these spots are visible only after 7-10 days of infestation. But with HSI, the infestation can be identified in the very early stages, and the problem can be treated with precision without any significant damage.

BharatRohan not only identifies the problems but also suggests the fixes. “The early-stage diagnosis of the biochemical changes in crops helps us create prescription on maps highlighted with the critical zones. An actionable advisory is given to the farmers. Our executives help farmers in its implementation. With precision and early diagnosis, farmers can apply the pesticides in the tract of land. They save on inputs and gain yields,” says Panwar, CEO, BharatRohan.

Filming the farms

Hyperspectral imaging is a technique that analyses a wide spectrum of light instead of just assigning primary colours (red, green, blue) to each pixel. The light striking each pixel is broken down into many different spectral bands in order to provide more information on what is imaged. The unique colour signature of an individual object can be detected. Unlike other optical technologies that can only scan for a single colour, HSI can distinguish the full colour spectrum in each pixel. BharatRohan can currently collect plant level and row level data at 5 cm/pixel resolution.

The use of drones is a big part of the Indian government’s push towards precision farming techniques. Under the Viksit Bharat scheme, the government would fund 15,000 rural women self-help groups (SHG) to the tune of 80% of the cost of a drone. The drones would be operated by trained women drone pilots called drone didis who are part of the SHG. Local farmers would be able to rent the drones for spraying fertilizer, sowing and monitoring crop health.

The interactions with farmers in the days of flying drones over their fields, helped Panwar and Choudhary learn first-hand about the damage caused by pests. They looked for ways to use their love for drones to help farmers. With a bit of research, they zeroed in on hyperspectral imaging, but it was too complex an area for two freshly-minted engineering graduates to venture into.

The mint experiment

The duo made cold calls to several experts in the field in India and overseas. They connected on Linkedin with Keshav Singh, an IIT-Mumbai alumnus and a post-doctoral researcher at University of California, Davis, specialising in the use of remote sensing technology and the use of unmanned aerial systems in precision agricultural applications. Singh was roped in early as partner.

Guidance, mentorship, and seed money came from ICAR’s a-IDEA incubator and CSIR’s Lucknow-based Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (CIMAP). Manoj Semwal, a senior scientist at CIMAP, helped BharatRohan create the spectral libraries for various crops and their diseases, starting with mint, potato and paddy, the three major crops in the Uttar Pradesh’s Barabanki district. The spectral library is a vast database that includes information about colour changes of a healthy plant grown in ideal conditions and those with specific diseases like the rust fungus in mint. Images from a farmer’s field can be juxtaposed with those from the library to precisely diagnose the occurrence of a disease, its stage and the nutritional status of the crop.

But every crop needs its own spectral library. To add information on a wide variety of crops, the company is working with the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), a Hyderabad-headquartered multilateral research organisation that works on millets and pulses that are the mainstay of farmers in the drylands of India and Africa.

The company’s drones can scour more than 10,000 acres of farmland every fortnight. BharatRohan uses artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) based tools to build proprietary models of analysis.

CIMAP introduced the two entrepreneurs to some 300 “progressive” mint farmers in region who were part of its own network. Having won a clutch of entrepreneurship grants from Indian School of Business (ISB), Rabobank and Government of India, BharatRohan began operations as a subscription-based service for the farmers in Barabanki in 2017.

Uttar Pradesh alone accounts for almost 70% of the global mint production. Natural mint oil finds extensive use in pharmaceutical, food and confectionery industries. Boosting yields Rakesh Kumar, an aromatic herbs farmer in the Fatehpur tehsil of Barabanki, a BharatRohan partner since 2017, says he and his fellow farmers were initially dismissive of the two youngsters who claimed to increase yields with the help of drones.

“After the results of the first 90-day mint crop, we had no doubt that it worked,” he says. According to Rakesh, the income from his nine acres of land where he grows mint, lemongrass, potato and paddy, has gone up 25% to Rs 12 lakh from Rs 9 lakh in the years he’s been working with the firm. Plus, he can save around Rs 3,500 per acre every crop cycle on inputs such as fertiliser and pesticides. For the advisory based on BharatRohan’s technology, farmers would pay 3% of their produce sales to the company.

But Panwar and Choudhary quickly realised that a business that depended entirely on getting farmers to pay might not be sustainable in India. In 2019, BharatRohan changed course to become an agriculture platform company that works with farmers from the sowing stage to post-harvest sales.

Will farmers pay up?

“Currently, we work with 19,000 farmers across 50,000 acres in six different states on a variety of crops. We adopt a farmer-friendly pricing model, charging based on the crop season. For instance, farmers cultivating crops over 3-4 months are charged approximately Rs 399 per acre per season. This approach ensures affordability for the farmers,” explains Panwar.

Using the data from drones, BharatRohan can offer farmers real advice through Whatsapp chatbots and on-field agronomists on caring for the crops.

The access to highly accurate data on fertilizer and chemical use by the farmers in its network makes it attractive for large food buyers to partner with the company. This also helps farmers with good quality produce that adheres to prescribed pesticide and chemical residue levels command a premium.

“In India, unlike start-ups in other sectors, ag-tech companies, even if they have a strong and scalable technology platform, find it very hard to raise venture capital funding for various reasons. Primarily, it is due to the investor fears about the uncertainties in India’s agriculture. But globally, given the stress on resources, high-tech precision farming is the next big thing. Innovations like BharatRohan will be the future,” says ICAR-NAARM’s Srinivas.

The nutmeg’s purse

Posted on March 6th, 2024

There are few places in Tamil Nadu more fetching and fertile than the region around Pollachi, a town 40km to the south of Coimbatore.

Girded by the Western Ghats, rivers that flow east from its peaks, amply fed by the southwest monsoon, and tropical forests, Pollachi’s soil can grow pretty much anything. It allows farmers to experiment with vanilla and cocoa to latch on to global commodity boom cycles. The region’s Eden-image was burnished by countless Tamil films that were shot here in the 1990s, and long-term prosperity built around coconut, especially tender coconut.

In recent years, nutmeg has considerably spiced up farmer incomes, thanks to the efforts of Ranjit Kumar.

Ranjit Kumar, 36, is a mechanical engineer who won the Chevening scholarship to pursue a postgraduate degree in nanotechnology at Cambridge University. When his father was diagnosed with kidney failure, he had no option but to chuck up a flourishing career in engineering design in 2016 and return to Kottur, a village 15km from Pollachi to manage the 60-acre family holding of primarily coconut plantation. While at Cambridge, Ranjit ensured diversification into nutmeg following a few other farmers in the region. It’s an ideal accompaniment to coconut in these parts. Nutmeg loves the shade of coconut.

Flavour bomb

The nutmeg fruit is the size of a table tennis ball and produces two spices—nutmeg and mace. It has a smooth, pale yellow exterior when ripe, somewhat similar to the apricot or plum. Inside the fleshy and aromatic fruit, the seed is clasped in a crimson filigree called mace, that when dried, resembles flower petals. Mace has a more delicate fragrance than the nutmeg. Enclosed within the hard kernel is the actual nutmeg, an oval-shaped marble that looks like the betelnut or supari. Both mace and nutmeg are prized spices. Besides food, the oil extracted from nutmeg is used in the perfume and pharmaceutical industries.

Trees can last up to 100 years and need little maintenance. It is naturally resistant to pests and needs only farmyard manure. Chemical fertilizers eat into the aroma of the spice.

Pollachi is a tiny nutmeg growing region compared to Kerala that accounts for more than 90% of the 15,000 tonnes India produces. Being a secondary production market, the nearly 150 nutmeg farmers in Pollachi with smaller output were at the mercy of a cartel of four traders.

“The farmers didn’t know much about market trends. Traders would tell us that our quality was poor and we took whatever money they offered. If you look at the organized services or manufacturing industry, the vendor and buyer are both informed parties. In agriculture, the farmer who is the vendor is in the dark,” says Ranjit.

In 2019, Ranjit started the Pollachi Nutmeg Farmer Producer Company bringing together 110 local nutmeg farmers.

A farmer producer company or FPC is a social enterprise that’s a hybrid between a cooperative, such as Amul, and a private limited company. An FPC can be formed when ten or more farmers in a region band together. But it must be owned and managed by its member-farmers.

Creating 10,000 FPCs across the country is a keystone in the government’s plans to increase chronically low small farmer incomes. To develop the FPC movement in the country, the government has made a budgetary allocation of Rs 6,865 crore besides a raft of other schemes to increase the access to money and markets for such companies. The power of collectivization through FPCs helps farmers negotiate better prices both when buying inputs like seeds and fertilizers or selling their produce to traders.

Understanding value

Instead of farmers selling small lots, the FPC pools more than 40 tonnes of nutmeg and two tonnes of mace from the member farmers across 50 villages.

Nutmegs are sorted by the farmers and graded in three quality tiers. All the produce is brought to a marriage hall in Pollachi and sold within ten days. Not only is their bargaining power better, the FPC can focus on marketing and attracting more buyers. As a result, farmer incomes have gone up almost 50% and the FPC has a turnover of Rs 2.5 crore.

A nutmeg tree starts yielding in about five years. A fully grown tree in Pollachi produces 400-450 nutmegs a year on average compared to a 1000 in Kerala. But in a wetter Kerala, the nutmegs are more susceptible to fungus.

Mace fetches a better price when it dries out turning yellow from scarlet while retaining its flower-like shape. “Due to the weather in Kerala, this process takes longer. Also, the nutmegs here have better flavour because the plantations are not as dense as in Kerala,” says Ranjit. A better understanding of the market and the value of their own produce is helping farmers convince the traders to offer a premium.

Farmers make up to Rs 180,000 a year in profits with 50 trees as an intercrop with coconut. Last season, one of the farmers in the FPC sold nutmegs worth more than Rs 20 lakh from his four acres. A kilo of nutmeg during peak season sells for more than Rs 450. When farmers sell small lots to traders, the average price can be as low as Rs 275.

Ranjit wants to replicate the success of nutmeg in coconut as well. That’s the big but elusive prize. It was easy to unite farmers through nutmeg because it is a high value commodity. The biggest crop in Pollachi is tender coconut—so big that most farmers have now lost the skill to grow anything else. In summers, the price of a nut goes up to Rs 35 and in winters farmers barely get Rs 10. “Our next target is to find a way to create a supply chain for tender coconut that keeps farmers profitable year-round. If you are not working collectively as farmers, you are moving in the wrong direction,” he says.

The young entrepreneur from Jharkhand who wants to simplify spiky jackfruit for India

Posted on February 17th, 2024

Like most young people born and raised in Jharkhand, Aman Chhabra, 31, was determined to find the escape velocity required to pull out of the state’s dark gravitational forces that could ground even modest ambition.

Being a bright student, he managed to attend Delhi’s prestigious Shriram College of Commerce. Post graduation, when he was expected to become a part of the family business running a hotel in Ramgarh, a town in central Jharkhand, Chhabra chose a career in event management instead.

His small but profitable startup organized flashy weddings for the super-rich in Mumbai and Delhi where A-list artistes performed and fine wine flowed from faucets. But the business couldn’t survive the crippling effect of Covid-19 in 2020. The search for a business idea that could survive such unforeseen shocks, and in sync with his own newfound life-motto of minimalism drove him to seek shelter under the copious, cool canopy of the jackfruit tree.

Under the jackfruit tree

Chhabra has joined the burgeoning corps of food entrepreneurs that wants to rekindle India’s love for the spiky, smelly, latex-laden sticky jackfruit.

His latest startup Kathalfy, seeks to simplify the consumption of jackfruit, called kathal in Hindi, in the form of ready-to-eat vegan packaged foods such as patties, keema masala, jackfruit makhni and assorted Indian curries.

Even if Chhabra had successfully plotted his way out of a state whose brazenly corrupt polity is a graveyard of entrepreneurial activity, memories of childhood were harder to shed.

“I grew up amidst jackfruit trees. Jackfruit was staple food. When I was researching sustainable business ideas, I realised India wastes almost Rs 2000 crore worth of jackfruit simply because we don’t know what to do with this abundance,” says Chhabra clad in a tight white Chinese-collar shirt, buttoned down to the wrist, a pair of denims and white sneakers, and hair cropped so short and sharp as to make his square jaw lend a rectangular shape to his face.

In recent years, jackfruit’s stock as a ‘superfood’ has skyrocketed globally.

There is increasing scientific evidence of jackfruit’s health benefits. A 100g serving of steamed, raw jackfruit has 40% less carbohydrates and up to four times more fibre than chapatis made from the same amount of wheat flour. The seeds in the jack pods contain a great deal of protein.

But even in India, the home of the jackfruit, the biggest tree-growing fruit in the world, Indians find it a nasty fruit. North Indians hate the ripe fruit for the smell they find unpleasant and, erm, reminiscent of excrement. In the south, jackfruit has an exalted status. According to ancient Tamil literature, it is part of the divine troika of fruits alongside mango and banana; its wood is used to make the mridangam. Yet, India wastes more than half of its two million tonnes of annual jackfruit output that leaves farmers with no option to treat it as a weed and chop the trees down.

Chhabra travelled around every major jackfruit mandi in India from Panruti in Tamil Nadu to Tumakuru in Karnataka to understand the fruit’s supply chain. He met up with scientists at the India Council for Agriculture Research (ICAR) and Central Food Technology Research Institute (CFTRI) working not only on developing new varieties of jackfruit but also processing to make it more industry and consumer friendly. While their work such as making chocolates out of jackfruit seeds that was called ‘Jackolate’ (we’ll leave you to judge branding) was interesting, no entrepreneur or business was keen on licensing the products and taking them to market.

Even if jackfruit grows prodigiously across peninsular India, especially along the coast, it is only Kerala that understands its many uses from the raw to ripe form, and has the capacity to process it at scale.

In Kerala, thinly sliced and steamed raw jackfruit is sometimes used as a healthier, fibrous carbohydrate alternative to rice.

Not surprisingly, James Joseph, another Kerala entrepreneur, has built a venture selling raw jackfruit flour under the brand Jackfruit 365 based on its ability to help diabetics.

Raw jackfruit chunks in the hands of a clever cook can be made to mimic pulled pork, or meat in a biryani. Chhabra’s quest for a contract manufacturer who could make ready-to-eat jackfruit products to his recipe brought him to a giant 20-acre food processing hub in Kerala’s picturesque Kolanchery town 30km to the east of Kochi.

Synthite, a large and local private firm with a long history of trading in spices grown in the Malabar coast, has set up what in marketing-speak it calls a ‘Taste Park’ in Kolanchery amidst ageing rubber plantations, a church at every bend of the hill-tract, and giant granite bungalows whose owners prefer to stay in Dubai or Denver, Colorado, US, than here. The dry January air can transmit the smell of instant noodles masala to anyone within a 3km-radius of the ‘Taste Park’. And for good reason. Synthite and its subsidiary Symega operating out of the ‘Park’, that makes Chhabra’s ready-to-eat jackfruit gravies, also produces spice blends, sauces, mayonnaise, and savoury processed foods for any major multinational brand you can think of.

According to Santosh Stephen, the managing director of Symega foods, a Rs 500-crore food processor, jackfruit-based, vegan ready-to-eat kebabs and curries is a huge market for his company globally. While a startup like Chhabra’s Kathalfy is merely seeding the market in India, large supermarket chains in US, Europe and Canada already sell seekh kebabs, samosas and cutlets made and packaged by Symega.

During the peak processing season for raw jackfruits between December and June, farmers can make up to Rs 30 a kg. While a ripe jackfruit can weigh as much as 15kg, the the raw form its only about a 3kg at best and its easy to transport, handle and process.

“The market for jackfruit products is huge globally. We have set up a dedicated division for plant-based foods made of jackfruit for our global customers,” says Stephen, a loyal Montblanc customer who uses the German luxury brand’s flagship Meisturstruck 149 fountain pens, belts and wallets.

For Chhabra, though, this seems the right time to make the abundantly available jackfruit more relatable to Indians without forcing them to change their palate.

“This can be a win-win for consumers and farmers. Why should we follow the West, when we have the raw material and knowledge to make jackfruit into the next big thing,” says Chhabra.

The humble jack might need government-led marketing campaigns like for millets for lift-off.

Tamil Nadu acid limes that basically offer a good deal without getting neighbours salty

Posted on February 2nd, 2024

Puliyangudi in Tamil literally means ‘tart territory’. Fittingly, the big boss in this Tamil Nadu town 140 km to the southwest of Madurai, on the foothills of Western Ghats bordering Kerala, is a sour fruit called acid lime that bears the scientific name Citrus aurantifolia.

While Puliyangudi acid lime’s application for the geographical indicator (GI) status is pending, it clearly commands a premium in the market.

With a paper thin two millimetre peel, the Puliyangudi acid lime has 50-55% juice content and is packed with flavour. A tiny nail-scratch on its surface is enough to make the juices and fragrance burst through. More importantly, it has a citric acid content of 8% compared to 5% in other lime varieties. Prices therefore can go up to Rs 500 a kg when demand peaks.

This small region’s tropical climate and red soil allows around 2500 farmers to produce nearly 10,000 tonnes of acid lime on 7500 hectares. Puliyangudi itself has become a large single commodity trading hub whose inhabitants take incredible pride in it being billed the ‘lemon town’. The proximity to a large consumption market in Kerala next door and the year-round demand for lemons in a hot country helps.

Even accounting for such factors, Puliyangudi’s acid lime-fame is arguably built on the base of a pioneering farmer and innovator called V Antonysamy. Now 83, Antonysamy is credited with developing several high-yielding varieties of acid lime that the region’s farmers have benefitted from.

His work not just on limes, but increasing sugarcane and rice yields through sustainable methods, has won him national acclaim too. With a 300-acre landholding, Antonysamy would rank among the wealthiest farmers in a country where farmers own less than two acres on average.

Antonysamy is a burly man with a round, chubby face, bald head and loads of, what locals consider, “attitude”.

Besides the white pick-up truck he drives, and the air of authority that occasionally creeps into his voice, there are few visible signs of prosperity that would make him an outlier in his surroundings.

After a breakfast of kambu koozh (a gruel made with bajra and buttermilk), Anthonysamy spends most of the day examining every tree and soil bed. His small eyes seem to be getting smaller with age, but the ability to spot something odd, here or there, remains intact.

“The farm wasn’t offered to me on a platter,” he says, clad in a white shirt, veshti and a typical farmers union green towel around his neck, trying to follow deer footmarks on soil made butter-soft by recent rains, to ascertain the damage done by nocturnal visitors.

Antonysamy joined his father’s farm in 1962 learning about Nature’s ways, the native science of soil management and weeds that helped and hampered the crop.

In the late 1980s, he developed a new lime breed from locally available varieties, by grafting and trial and error, that could almost triple the output.

That led to Puliyangudi’s acid lime boom and its demand in the food processing industry in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

On average, acid lime cultivation can fetch farmers a net profit of Rs 200,000 per acre a year, accounting for seasonal price fluctuations.

“In the last decade, acid lime productivity has increased 25-30%. Farmers now get more than 1000 fruits a tree on average compared to 700-750,” says Palani Kumar, Head (Horticulture), Citrus Research Station and Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU), Sankarankovil.

However, climate change is proving a party-pooper.

Every morning, with his lunch packed in a steel tiffin box, 62-year-old Abdul Wahab rides a 100cc TVS moped to his acid lime orchard in Konandoppu Aaru village in the Puliyangudi region. It’s a big improvement on the bicycle he used until a decade ago.

By December, his lime trees should have bunches of pearl-white flowers. But the northeast monsoon rains, delayed by almost two months, that battered southern Tamil Nadu, have knocked the flowers off. The unseasonal deluge has also resulted in citrus canker, a bacterial disease that devours citrus leaves. Wahab needs to prune several thousand afflicted branches carefully to ensure he has any marketable output during the April-May harvest season. The interest on the money he has borrowed from a local loan shark would grow as fast as the weeds around his acid lime.

“Better farm management with increased use of organic manure, mulching and pruning can overcome such issues,” says Antonysamy.

A GI tag for Puliyangudi acid lime can only make farmers’ prospects better.

Vijayalakshmi Sridhar is a business, technology, food and environment writer based in Chennai.

How an Indore agripreneur couple is using moringa to fight malnutrition

Posted on January 31st, 2024

Moringa or drumstick and sambar is a match made in food heaven. Yet, it struggles to cross the Vindhyas into India’s north. The green, ribbed sticks floating in a bowl of sambar offer a puzzle. The perfect way to deal with drumstick is to first suck up its juices like marrow from the bone, then poke an end with the index finger to split it open, scoop out the jelly like flesh with three fingers, scrape it clean with lower incisors, and finally chew it up until the piece of drumstick resembles a spent sugar cane at a juice shop. Of course, all of it can seem savage for those uninitiated in southern culinary culture!

In the ancient Tamil tradition of Siddha medicine, the moringa tree is has the status of a superstar. Its leaves, flowers, bark and the drumstick itself are believed to be a cure for impotency to anemia and several other ailments in between. A moringa tree in the backyard was thought to be guarantor of good health. While drumstick as a vegetable remains under appreciated, there is now huge interest globally in harnessing the tree’s benefits in fighting malnutrition and lifestyle diseases, especially post-Covid 19.

The ‘miracle tree’

Pallavi and Sanjay Vyas, an Indore based agri-entrepreneur couple, too, is betting big on the ‘miracle tree’ called moringa. Their firm Shanta Farms sells moringa based cattle feed, human nutrition supplements and even a patented, chocolate-flavoured based moringa milk additive beverage called Morvita positioned as a healthy substitute for popular malted wheat brands such as Boost and Bournvita.

It’s a business opportunity they discovered almost by accident.

The Vyases ran a thriving organic dairy business focusing on indigenous cow breeds. The farm at its peak spread over nearly 40 acres with more than 200 cows. A chance meeting in 2015 with Giriraj Singh, a BJP MP from Bihar’s Begusarai and currently the Union Minister for animal husbandry and fisheries introduced them to moringa. “Nobody knew anything about moringa here till a few years ago. Even now it is hard to convince people to grow or eat it. When Giriraj Singh visited our dairy, he asked us to try out moringa as cow fodder,” says Pallavi Vyas, the a 45-year-old cofounder of Shanta Farms.

The advice seemed to work. Using moringa leaves as fresh fodder, silage and dried showed a 30% increase in productivity in six months. “Moringa was a nutrition dynamite. It helped prevent diseases like mastitis, fertility of cows went up, our veterinary bills fell sharply and we could completely stop spending on multivitamins and supplements for cows,” says Pallavi.

Being native to India, moringa can be grown pretty much in every part of India. It is especially adaptable to arid regions with poor rainfall and soil.

Over the next few years, the Vyases worked on dehydrating and processing the moringa leaves as a human health and immunity booster.

“In granulated form, moringa has ten times more vitamin A than carrots, 25 times more iron than spinach and nine times the protein in yoghurt. Following ayurvedic principles we developed a process for granulating moringa to fight anemia and malnutrition for which we have received a patent,” says Pallavi Vyas. During Covid-19, the couple worked with anganwadis and local government schools in Madhya Pradesh on pilot basis where children were given moringa supplements. “It was highly effective in tackling malnutrition with even the most stunted children gaining 200-300 grams in a month,” says Vyas.

A big business opportunity

According to Pallavi the company has pretty much shut down it’s dairy operations and is now focused on taking moringa products national. “With organic dairy, we found it hard to create a pan-India business. But with moringa, we see an opportunity to create a Rs 500 crore brand. Currently we make animal fodder, supplements for even carnivorous zoo animals and human nutrition products. We’ve barely begun work of moringa-based beauty and cosmetics products which is a massive opportunity,” she adds.

This young woman CEO fights hard to make farmers richer in Tamil Nadu’s remote corner

Posted on January 16th, 2024

In the arid region of Thoothukudi, a coastal district at the chin of Tamil Nadu 600 km to the south of Chennai, it’s not just the buildings but also tempers that get corroded quickly by the salty air.

At around 11 am on a late December morning, when the sun beats down without baking the skin, an agitated mob of a dozen farmers has gathered at the basketball court-sized office of Vilathikulam Pudur Pulses Producer Company (VPPPC), a farmer producer company (FPC) in Vilathikulam Pudur, a panchayat town 60 km from Thoothukudi.

The angry farmers who are members and shareholders in the company demand to meet Bavithra Jagatheshkumar, the CEO.

A farmer producer company or FPC is a social enterprise that’s a hybrid between a cooperative, such as Amul, and a private limited company. An FPC can be formed when ten or more farmers in a region band together. But it has to be owned and managed by its member-farmers.

Creating 10,000 FPCs across the country is a keystone in the government’s plans to increase chronically low small farmer incomes. To develop the FPC movement in the country, the government has made a budgetary allocation of Rs 6,865 crore besides a raft of other schemes to increase the access to money and markets for such companies. The power of collectivization through FPCs helps farmers negotiate better prices both when buying inputs like seeds and fertilizers or selling their produce to traders.

Farmer anger

The grievances of the group of farmers who have accosted Bavithra are many. Some of them have not received the bag of fertilizer they had ordered. But there’s a bigger problem. Rumour has it that Bavithra has not paid up the monthly installment for the bank loan the FPC has taken on behalf of its members.

Thirty-one-year-old Bavithra, a stocky woman clad in grey salwar-kameez, hair tied into a bun, wearing a rudraksha bead around the neck and vibhuti, or sacred ash, that runs across her forehead temple to temple, offers them tea in little steel tumblers and assurances in mellow tones, referring to the farmers as anna (brother) and appa (father), that no bank dues are pending.

Matters of caste lend a sharper edge to the confrontation. Farmers in this group are overwhelmingly Kambalathu Nayakars, a community classified in Tamil Nadu as ‘most backward’. Veerapandiya Kattabomman, an 18th century local chieftain who rebelled against the British Raj by refusing to pay taxes, belonged to this group. Kattabomman was played by Tamil star Sivaji Ganesan in a classic 1959 film.

While Kambalathu Nayakars are numerically tiny in the state, this region is one of their few strongholds. Bavithra on the other hand is a Thevar, one of the most influential backward castes in the state, but a small minority here.

When bank challans and other documentary evidence don’t work, she offers them Rs 2000 to hire a van to go meet the bank manager in person, to diffuse issue.

“Most meetings with farmers are like this only,” says Bavithra, mustering a girly smile. Without Bavithra’s tenacity to stand up to caste and gender prejudices, skills of diplomacy and a single-minded vision to improve the economic prospects of 1500 shareholder-farmers in the FPC, it wouldn’t have been possible to turn around a failing company with no income in 2019 to one with Rs 14 crore in revenue and a profit of around Rs 25 lakh today.

VPPPC was among the 57 FPCs promoted by the agricultural marketing department of Tamil Nadu in 2016 under the National Agricultural Development Programme (NADP) scheme with a mandate to improve the livelihoods of the pulse producers in the region. Today, only 12 have survived. VPPPC which Bavithra runs is widely considered a role model.

Low cash flow

Thoothukudi is a relatively prosperous district in Tamil Nadu with a per capita income of Rs 2.04 lakh compared to the state’s Rs 2.4 lakh a year. Its economy is built around the sea port, small and medium manufacturing firms and trucking. Agriculture in the region is almost entirely rainfed. All farming activity is restricted to a few months before and after the north east monsoon in October-November. Dryland crops such as chilli, coriander, pulses, lime and millets dominate the landscape.

The FPC in Vilathikulam Pudur was promoted by the government to collectivize farmers and help them get a better deal through economies of scale when they purchased inputs such as fertilizers or sold their produce.

Bavithra is a graduate from the College of Agri Technology in Theni, a town 80 km west of Madurai on the foothills of the Western Ghats best known for producing Tamil film icons such as composer Ilaiyaraaja and director Bharatiraaja. When she was appointed the CEO of the company, it was pretty much defunct verging on closure.

Bright, young agri graduates such as Bavithra are often hired by organizations that promote FPCs to run them.

Bavithra built up the business at breakneck speed opening a millet and grain processing unit, mushroom farms, breeding livestock, manufacturing cattle fodder and retail outlets selling farm inputs. A small slaughterhouse and modern meat packing unit aimed at modern trade and export markets with an investment of Rs 10 crore will be up soon.

Gaining trust

“Her ability to understand the context of the region, its people and business, and make the business thrive is phenomenal,” says R Narayanan, chief marketing officer, Samunnati, a Chennai-based company that finances FPCs, creates market linkages for them and offers advisory services.

The first problem Bavithra identified was the very nature of farming and its economics in Thoothukudi. In this rainfed region, farming is a remotely gainful activity only for a few months of the year around the north east monsoon season, there is no money supply in the agri system for the rest of the year. If farmers diversified into mushroom cultivation, poultry and goat rearing it would improve the flow of cash. “She convinced Canara bank to lend farmers Rs 10-12 crore through the FPC so that they could start off diversifying. VPPCL went door-to-door disbursing loans to the member farmers and they would queue up to repay. It is astonishing that Bavithra’s FPC has a near-zero delinquency rate on loans,” adds Samunnati’s Narayanan.

When Bavithra was appointed VPPPC’s CEO in 2019, it had only about 800 members and teetered on the brink. Its two remaining employees were ready to quit because they hadn’t been paid for six months.

She persuaded them to stay on by paying almost all the money due to them from her pocket. With them in tow, she visited the 61 villages under VPPPC and met the farmers in person. She patiently explained she had come to improve their livelihoods and that VPPPC was planning to work with them in a mutually beneficial manner. She needed more members and their co-operation to make it sustainable. She chose the board of directors (BOD) for the company to carefully ensure fair representation of various caste groups and geographies within VPPPC’s catchment area. Three of the five BODs are women.

“Her patient communication and determination worked. From 823, the membership rose to 1500,” says Sudharani. M, a local farmer.

Having galvanized membership, Bavithra started looking for avenues to build on their capacities and resources for generating more revenue. At that time, VPPPC’s operation was limited to running an agri input store with few things to sell.

“Male farmers often try to put me down. They say, ‘what does this papa [girl child] know about farming.’ I’m from a family of farmers and studied agriculture but have grown up in a big city like Madurai. I have a fair understanding of farming and business. It is not difficult for me to ignore the sexist barbs and do what is good for farmers,” says Bavithra in a tone that’s utterly unsentimental.

Loan lifeline

In 2019, before the year’s cultivation season commenced, through the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme, Bavithra signed the guarantee for sanction of a Rs 3.5 crore loan for 350 farmers in Vilathikulam Pudur. With a track record of poor recovery, KCC was a widely rejected scheme; none of the banks was ready to reboot it. With Bavithra’s persistence, Canara bank agreed to facilitate the loan. The first disbursement at the rate of Rs 1 lakh per farmer with a one-year tenure was made for those who were ready to sign a bond with her. Without any hassle, the cultivation was wrapped up on time and the farmers repaid the loan soon after.

This helped Bavithra gain the farmers’ trust.

“Bavithra has succeeded because she has great management skills. As a long-time member of VPPPC I will fully support her and her initiatives,” says A. Murugavel, a farmer-member of VPPPC from a village called Muthusamypuram.

In 2020, at the peak of Covid-19 lockdown, the state agricultural marketing department enlisted VPC to organize mobile carts to supply villages in the area with vegetables sourced from Madurai and Aruppukottai. The demand for essentials during the crisis was such that Bavithra added groceries too to the mobile carts. VPPPC’s sales skyrocketed from Rs 10 lakh to Rs 60 lakh. “For us, it was an unexpected boom in the time of tragedy,” recalls Bavithra, now married to a local taxi fleet operator and a mother of two young boys.

Hedging bets

She applied for grant funding under the Mission on Sustainable Dry Land Agriculture (MSDA), a government scheme aimed at helping dryland farming. Bavithra bagged the Rs 20 lakh grant. With an additional working capital of Rs 5 lakh in the form of loans, she invested in millet and oil processing units. The unit started generating daily income by milling flour for the local population.

As part of a private firm’s Covid-19 relief drive, the FPC bagged a big order to supply oil sachets to the poor. To fulfill the order, VPPPC procured sunflower and groundnut seeds from farmers, initially on credit basis. Close to 8000 litres of oil production brought in further revenue of Rs 60 lakh.

The farmers were ready to take the pulp and seeds left after crushing to feed the goats and sheep. Identifying the demand for feed, VPPPC set up a cattle feed shop. A veterinary pharmacy followed.

With a productive, profitable portfolio in hand, Bavithra approached Samunnati for a working capital loan to expand the agri inputs business. In three months, sales doubled helping her open a supermarket called Marudham selling mostly local produce.

Thoothukudi district has the right agro-climatic conditions for breeding kodi aadu, a type of country goat that has long legs and lanky appearance, reared for meat. But the rate of mortality was high. As an experiment, Bavithra purchased six baby goats and reared them at a farm owned by one of the BODs. When the number multiplied to 13, a goat farm was set up in a rented establishment. Today, the farm buys farmers’ goats and also sells healthy foals to them. Now there are 250 goats in the farm that are ready for sale.

VPPPC has successfully created better market access for farmers, helped them tap various state and central government schemes, and trained them to tap opportunities for value addition.

“Bavithra’s committed approach has transformed the farmers’ enthusiasm to collaborate and grow,” says A Balamurugan, a state agriculture officer in region.

Despite her successes, Bavithra’s ambition is to become an officer in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS). Perhaps it’s a desire that stems from her struggles to bring change without the State’s backing. “I will have more power to implement ideas that are good for farmers. They will listen to me more readily,” she says.

“Look, Samunnati or any private sector company in the agri sector would hire Bavithra without batting an eyelid with her skills of leadership and the ability to execute ideas,” says Samunnati’s Narayanan.

Government’s gain would be a big loss for Vilathikulam’s farmers.

Vijayalakshmi Sridhar is a business, technology, food and environment writer based in Chennai.

MS Swaminathan was an inspiration and hero to scientists the world over

Posted on October 8th, 2023

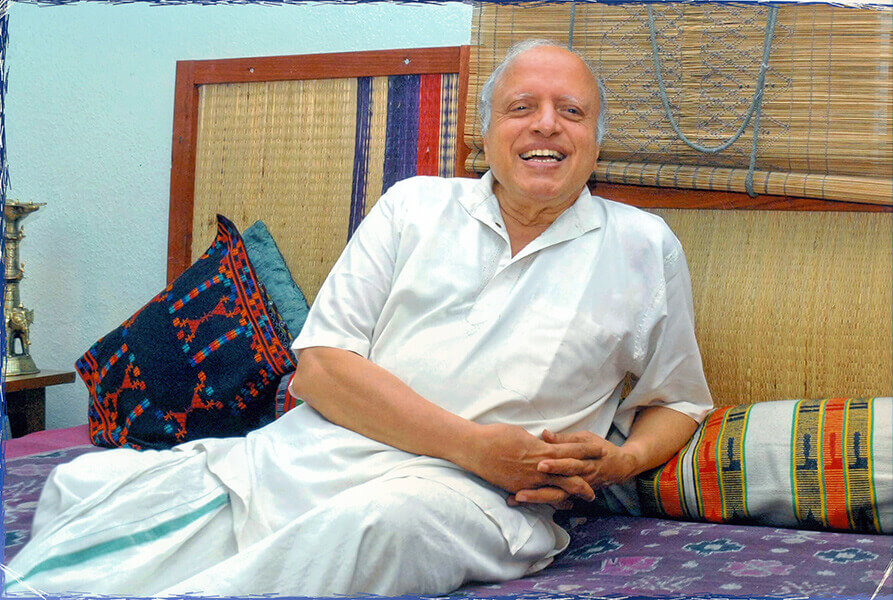

In the annals of India’s agricultural history, one name stands out brilliantly–MS Swaminathan, popularly known as MSS. His passing away, at the age of 98 years, on September 28, 2023 in Chennai has left a void that can never be filled, but his indomitable spirit and vision will continue to inspire generations of young scientists and shape the course of agriculture for years to come.

International impact

Born on August 7, 1925, in Kumbakonam, Swaminathan dedicated his life for the betterment of humanity through his pioneering work in agriculture and food security. He was instrumental in developing high-yielding crop varieties that led to a significant increase in food production between 1960 and 1970, making India self-sufficient in food and dispelling looming fears of famine. For this monumental contribution, he is hailed as the ‘Father of India’s Green Revolution’. Professor Swaminathan’s research contributions to agriculture were not confined to India alone. He actively collaborated with international organizations, including Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers (CGIAR), UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and UNESCO leveraging his vast knowledge and expertise to tackle global food security challenges. Notably, he played a key role in the establishment of the International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in India (where I worked for 17 years), the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (now known as Biodiversity International) in Italy and the International Council for Research in Agro-Forestry in Kenya. His guidance was instrumental in shaping numerous institutions in China, Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Iran, and Cambodia.

Swaminathan had a distinguished educational background. He pursued his BSc at the University of Kerala and Tamil Nadu Agricultural University. He completed his MSc from the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) and was a UNESCO Fellow at Wageningen Agricultural University. Subsequently, he earned his PhD from the University of Cambridge and undertook post-doctoral studies at the University of Wisconsin. In a defining decision, he declined a faculty position in the USA, choosing to return to India in 1954 to drive impactful change in his homeland. Subsequently, he served the Central Rice Research Institute, IARI, and then the Indian Council of Agricultural Research as well as international organizations in various roles. He served as Director of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (1966-72), Director General of ICAR and Secretary to the Government of India, Department of Agricultural Research and Education (1972-79), Principal Secretary, Ministry of Agriculture (1979-80), Acting Deputy Chairman and later Member (Science and Agriculture), Planning Commission (1980-82) and Director General, International Rice Research Institute, the Philippines (1982-88). One of his most pivotal roles came in 2004 when he was appointed chair of the National Commission on Farmers. This commission was established in response to rising farmer distress and alarming rates of suicides among farmers. The commission’s report, submitted in 2006, made several recommendations. A prominent suggestion was that the minimum selling price (MSP) should be at least 50% above the weighted average cost of production.

Farmers’ friend

Swaminathan was a steadfast advocate for smallholder farmers and sustainable farming practices. He passionately believed in harnessing the power of science to uplift the marginalized. As a staunch supporter of equipping farmers with the knowledge and resources they need, he envisioned a holistic approach to agriculture. This approach emphasizes the significance of preserving biodiversity, conserving natural resources, and adopting environmentally friendly farming techniques. To further this cause, he founded the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) in 1988. Since its inception, he had been dedicatedly serving and, in recent times, guiding MSSRF in its mission to develop and promote strategies for economic growth. These strategies are primarily aimed at increasing the employment opportunities for impoverished women in rural areas.

A lodestar for Indian scientists

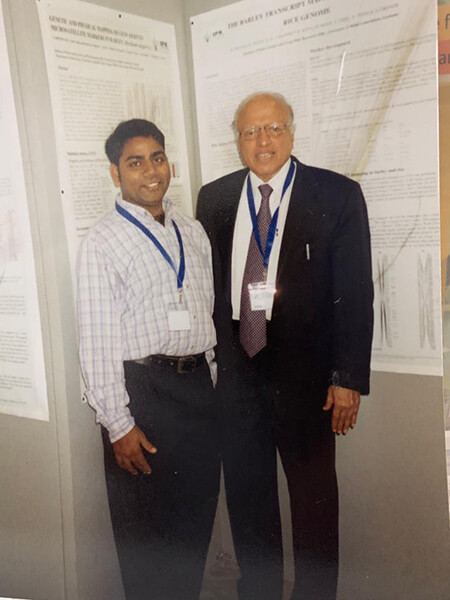

Having Swaminathan as an inspiration in my early career (my PhD in India and Post-doc in Germany) and then a mentor and guide since joining ICRISAT in 2005, has been a privilege and instrumental for my research career. His humility, warmth, and passion for agriculture were palpable. He was always eager to listen to young scientists, to encourage new ideas, and to guide them on the path of innovation. I learnt the importance of interdisciplinary research and collaboration from him as he always emphasized that the challenges of agriculture required a holistic approach. That’s what I adopted during my tenure at ICRISAT for 17 years (2005-2022) and continue to deploy at Murdoch University.

I first met Swaminathan during my early days as a PhD student when I attended a conference organized by him and the late Lalji Singh at MSSRF in 1999. At that conference, I received the Best Poster Award (along with a cash prize of Rs 2000!) from Swaminathan. It remains one of the most joyous moments of my life. I then met him again in 2000 at the 2nd International Crop Science Congress in Hamburg, Germany. While I was in Germany from 2001 to 2005, I stayed in touch with Swaminathan through letters and emails. However, after joining ICRISAT in 2005, I had the privilege of interacting with him more frequently. Our numerous meetings and interactions took place at ICRISAT, MSSRF, and other locations in India and abroad. I invited him to deliver keynote speeches at several international conferences. Similarly, I attended many meetings organized by Swaminathan at MSSRF in Chennai.

Swaminathan’s life was remarkable, marked by dedication, innovation, and a profound love for the land. I recall an interaction with him during an FAO meeting in Bangkok in 2016. Despite being on a wheelchair, he was among the invited experts. Considering his advanced age and mobility challenges, I said, “Sir, you have already contributed so much to international agriculture. Perhaps you shouldn’t strain yourself by travelling so extensively.” Before I could finish, he replied, “Rajeev, interacting with young minds like yours at scientific meetings keeps me abreast of the latest advancements in agricultural science. That’s what motivates and energizes me to travel at this age.” He added, “I can’t imagine just sitting in my office when I believe I can still make a contribution to society.”

Indeed, I believe that the qualities exemplified by Swaminathan have been passed down to his children. His three daughters are proud bearers of his legacy–Soumya Swaminathan, formerly the Chief Scientist with the World Health Organization (WHO) and now the Chairperson of MSSRF; Dr. Madhura Swaminathan, an economist and Professor at the Economic Analysis Unit of the Indian Statistical Institute in Bangalore; and Nitya Swaminathan, a specialist in gender and rural development. All of them are actively contributing to societal change and human welfare.

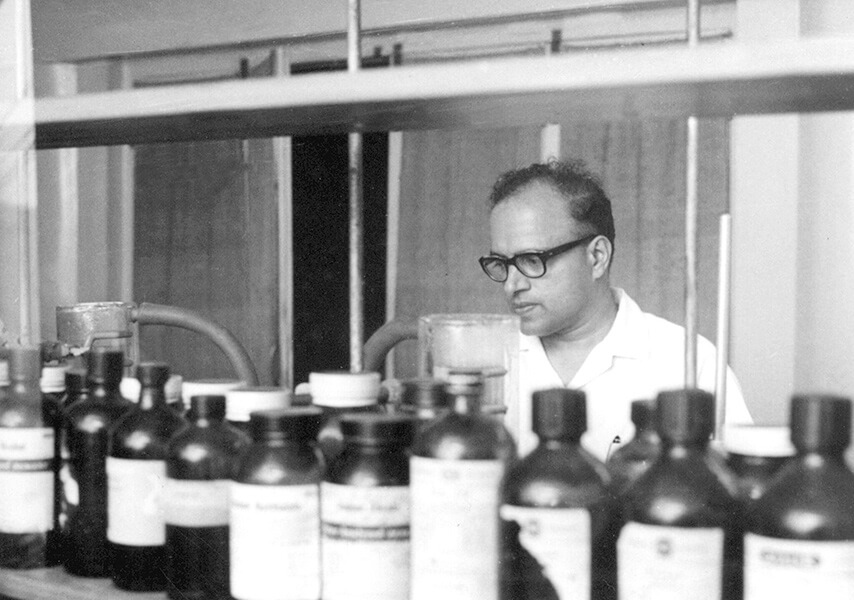

Having been immersed in genome sequencing since 2007, I’ve always been intrigued by the secret behind Swaminathan’s boundless energy, enthusiasm, and intelligence. So, when he visited our Genomics Centre at ICRISAT, we asked if he’d be willing to provide a blood sample. With the support and collaboration of CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology and BGI-Shenzhen (China), we isolated his DNA, sequenced, and analyzed his genome. I had the honour of presenting his genome sequence (stored on a pen drive) to Swaminathan on his 90th birthday at MSSRF in 2015.

“When I was working on my PhD, I began to understand the double helical structure of DNA. But I never imagined I’d one day hold the fully decoded sequence of my own genome in my hands,” he said.

Such moments and interactions have served as a beacon of inspiration for countless young minds in agricultural sciences, both in India and internationally.

A lasting legacy

Swaminathan was not just a towering figure in agricultural science, but a genuine hero. His illustrious career was marked with countless awards and accolades, including Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award, the Ramon Magsaysay Award, and the Albert Einstein World Science Award, Fellow of The Royal Society, Padma Shri, Padma Bhushan, Padma Vibhushan, World Food Prize. I feel privileged to be one of few Indian agricultural scientists following in his footsteps to receive Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award and become a Fellow of The Royal Society. It was a moment of immense pride for me when upon informing Swaminathan of my election to the FRS in May 2023, I received his warm congratulatory message the very next day. He wrote “I am very happy to note that you have been elected as a Fellow of Royal Society. Kindly accept my congratulations and very best wishes on your well deserved accomplishment. A Fellow is someone who makes an “original contribution.” I wish you good health and much happiness.” That message remains my final cherished communication with him. During my conferment as an FRS at The Royal Society in July 2023, I was shown the esteemed 363-year-old Royal Society Charter, which bore the signatures of all its Fellows. The very first signature I sought was Swaminathan’s, inscribed in 1973. Finding and holding his signature filled me with elation; it was as if I was floating on cloud nine.

In closing, while we mourn the loss of Prof Swaminathan, we must also celebrate his enduring legacy. He exemplified how science can serve as a catalyst for positive change, demonstrating that research can and should be channelled to address tangible challenges. His tireless efforts and unwavering commitment to the cause of agriculture served as an inspiration for us all. We were motivated to follow in his footsteps, to carry forward his legacy, and to contribute to the growth and prosperity of agriculture. His legacy continues to inspire researchers, policymakers, and advocates worldwide to address the pressing challenges of our time, from climate change to sustainable agriculture.

Rajeev Varshney is Director of the Centre for Crop & Food Innovation, Director, State Agricultural Biotechnology Centre and International Chair in Agriculture & Food Security with the Murdoch University, Australia. This piece first appeared in his blog.

MS Swaminathan: architect of Green Revolution; the greatest Indian since Gandhi

Posted on October 6th, 2023

On the occasion of India’s 65th anniversary of Independence, television channels CNN-IBN (now CNN News18), History Channel, and Outlook magazine jointly ran an audience poll, steered by a panel of “experts”, to ascertain the ‘Greatest Indian after Gandhi’.

Mankombu Sambasivan Swaminathan, who passed on at the age of 98 on September 28, 2023, barely made it to a shortlist of 50, let alone the Top 10 that contained Sachin Tendulkar and Lata Mangeshkar in a club overwhelmingly comprising politicians.

Such lists are gimmicks anyway and a result of political partisanship, recency bias and media narratives.

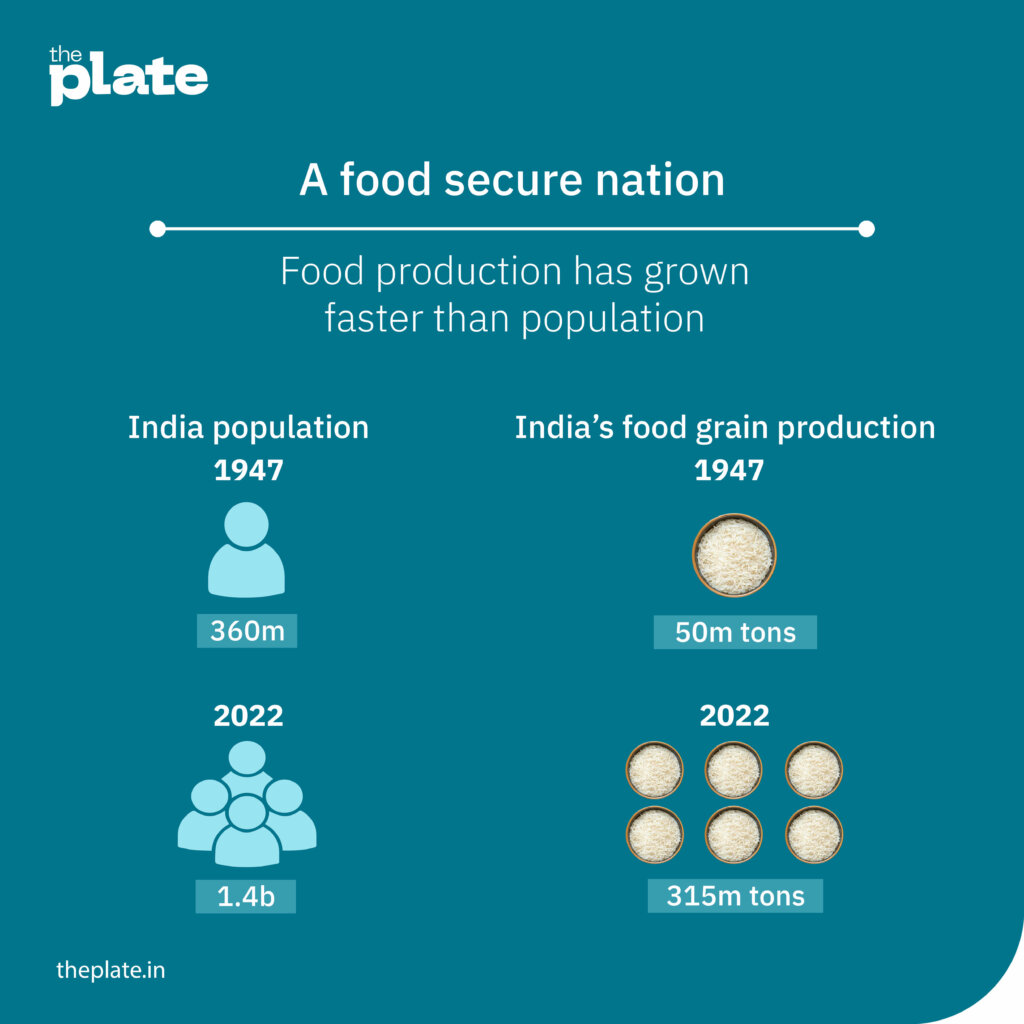

In this writer’s view, with no disrespect to those of yours, there isn’t anyone more worthy of the tag ‘greatest Indian since Independence’ than Dr MS Swaminathan. He provided the bedrock of science and built institutions up from scratch with scant resources to usher in the Green Revolution. His contributions made India not just food self-sufficient, helped 800 million poor escape hunger, but also turned it into a leading producer of every major agricultural commodity.

Faith and food

Swaminathan can be seen as the male embodiment of Annapoorna, a form of Parvati, the Hindu deity of food and nourishment, holding in one hand a Leitz binocular research microscope and his field notes in another, instead of the pot and ladle filled with food in popular religious iconography.

That both the Goddess of nourishment and Swaminathan, the scientific guarantor of food security, are now relegated in public consciousness are a measure of India’s progress and the liberty we now have to take access to food for granted.

Hungry nation

To understand the importance of Swaminathan’s work, it is instructive to survey the first twenty five years of Independent India’s history.

By 1962, India was a basket case; the doomsayer’s dream come true; a nation humiliated on the battlefield and stripped of its self-esteem, living on Western food-aid.

During the disastrous war with China in 1962, Prime Minister Nehru’s letter to US President John F Kennedy seeking help to ensure the very “survival of India ” wasn’t forwarded for a week because of its “naked desperation”. In any case the US didn’t respond because it was preoccupied with the Soviet Union planning to deploy nuclear missiles closer home in Cuba.

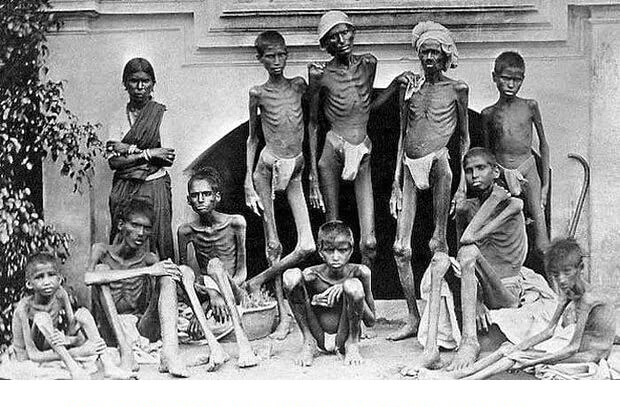

The Bengal famine of 1943 which starved 3.5 million Indians to death had a profound impact not just on the freedom movement but also in the politics and the policy course of free India.

“After decades of marches, boycotts, and strikes in protest of the economic consequences of imperial rule, the Bengal famine marked, in Jawaharlal Nehru’s words, ‘the final judgement on British rule in India.’ As India’s citizens and politicians reflected upon the famine, they saw in it the clearest failure of colonial politics and economics, tying the promise of self- rule to the project of sustenance for every Indian. Famine had long been central to Indian understandings of imperial injustice, but after 1943, the elimination of hunger emerged as a nationalist imperative,” writes Benjamin Seigel, a Boston University historian of politics, agriculture, and the environment, in his 2018 book Hungry Nation.

Farm versus factory

But stagnant agriculture and a crippled industry meant the python-grip of hunger only got tighter in the two decades post-Independence.

The economic model India pursued under Nehru’s leadership involved top-down industrialization. The government through the companies it owned would make steel, electricity and the heavy machinery needed to create ‘New India’. The only way to fund all of this was to suck agriculture dry. Nearly 90% of the country’s population was agrarian and farming drove most of the economic activity.

“Borrowing large sums from abroad was out of the question—India didn’t have the stores of foreign exchange that would be necessary to repay the loans. Funds for industrialization therefore had to come from India itself. Creating an industrial economy thus implied skimming off the profits from rural peasants and using that money to build steel mills, power plants, and highways in urban areas. Like [Mahatma] Gandhi, Nehru was sympathetic to the plight of poor farmers. Nonetheless, his ideas about development unavoidably led him to drain the agricultural countryside to benefit the industrial cities,” writes Charles Mann, a US journalist and science writer in his book The Wizard and The Prophet that looks at the lives of scientists Norman Borlaug and William Vogt, the greatest 20th century influences on agricultural science and environmentalism respectively.

Begging bowl

This policy resulted in abject underinvestment in agriculture. The government-led heavy industry plan too was built on a shaky foundation in the absence of a small and medium industrial base of private entrepreneurship.

As early as 1950, India had to approach the US for 2 million tonnes of grain in desperate food aid. The request was a significant turning point not just for India. The US realized the power of such aid. It was soon packaged as the ‘food for peace’ programme– a potent Cold War weapon to prevent newly independent countries such as India joining the Soviet camp.

In 1954, US passed a law popularly known as PL480 that allowed the American government to dispose its surplus grain abroad at highly subsidized rates.

Hot meal in Cold War

In one stroke, the US could get rid of surplus food and keep domestic farm prices stable, while using the excess as part of the global policy to contain communism. Between 1956 when India signed a deal with the US under the PL 480 plan, up to 1970, it received nearly 65 million tonnes of cheap wheat (almost half of India’s current annual production). India paid for PL 480 grain in rupees, held by the American government in India. The money was to be spent in the country in the form of development investments. By the 1970, it is estimated that PL 480 payments gave the US control of as much as one-third of India’s total money supply.

“It was almost as if the Americans had bought a big piece of India with grain,” wrote John F Perkins, a scientist and historian in the book Geopolitics and the Green Revolution.

The addiction to cheap American wheat was so big and the incentive to increase domestic farm production so little that the average wheat yields of about 700-900 kg per hectare until 1965 was no different from the time of the Mughal empire in the 16th century.

Cheap imported wheat allowed the government to open a bread-making business under the brand Modern Foods (now owned by Unilever India) to keep up with urban food demand.

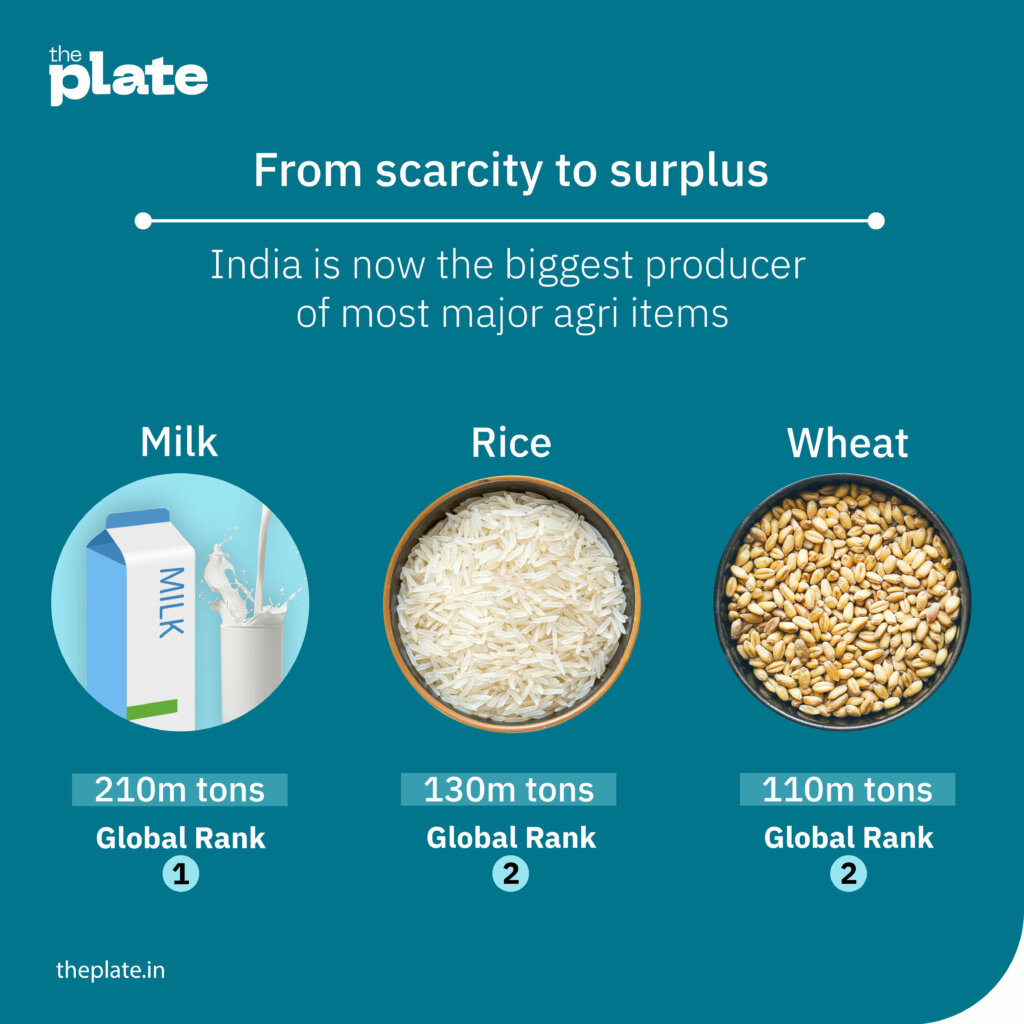

Today, India is among the world’s largest producers of every major agricultural commodity including rice, wheat, cotton, sugar and fruits and vegetables. Despite the Covid-19 lockdown, and the disruption of global trade due to the war in Ukraine, India remains relatively hunger free and food self-sufficient.

We have to thank MS Swaminathan, the principal architect of India’s Green Revolution and for his pivotal role in upending the paradigm of penury in the country.

Famine warrior

Swaminathan was born in 1925, in Kumbakonam, to parents committed to India’s freedom movement. His father was a medical doctor who set up practice in the heart of the Kaveri delta, far away from the ancestral home in Mankombu, a village in the lowlands of Kerala’s southern coast. Swaminathan’s father Sadasivan was devoted to helping fight the mosquito-transmitted disease called filariasis that made human legs swell so much to resemble an elephant’s.

“He mobilized school children to identify mosquito breeding grounds, then asked their parents to fill in stagnant pools and move garbage dumps and disinfect drains and sewers. New cases of the disease ceased to occur—a lesson, Swaminathan said later, in the power of collective action,” writes Charles Mann.

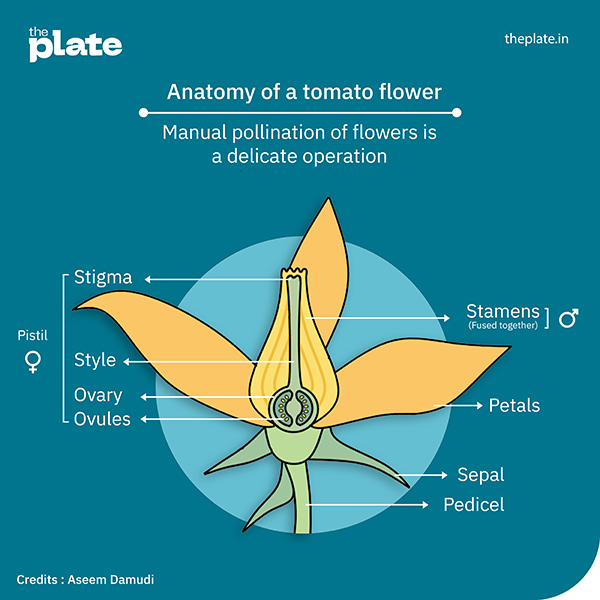

Swaminathan wanted to become a doctor like his father, but the horrific stories of famine deaths in Bengal steeled his resolve to help India find a way out of hunger. After a bachelor’s degree in botany at Thiruvanthapuram’s University College (a prerequisite course for pursuing medicine) Swaminathan enrolled into another bachelor’s course at the Coimbatore Agriculture College. There he graduated at the top of his class, and won almost every award on offer. A postgraduate research scholarship to study at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) in New Delhi followed. Swaminathan’s task there was to work on the solanaceae, a family of plants that includes tomatoes, potatoes, chillies and brinjal. In the meantime, at the prodding of relatives who were convinced that it was impossible to make a career in agri sciences, he had also passed the civil services examination in 1949. His rank allowed him to join the Indian Police Service (IPS), and he almost became a police officer. Luckily, for India and Swaminathan, he won a UNESCO fellowship at around the same time to study at Wageningen University, the Dutch national agricultural school.

“The Netherlands was just recovering from the war; famine of 1944–45 was a fresh memory. The university labs lacked heat and sometimes electricity. Swaminathan was asked to switch from brinjals to potatoes, a Dutch staple. Dutch potato fields were aswarm with parasitic nematodes. Wageningen was trying to fight them by breeding domesticated potatoes to wild, nematode-resistant relatives. But the wild and domesticated species had different numbers of chromosomes, which usually makes successful breeding impossible. Swaminathan figured out a workaround. The discovery was valuable enough to bring him to Cambridge University, in England, where he finished his PhD,” writes Mann.

A new breed

Swaminathan became one of the global pioneers in plant cytogenetics, a field of study on how chromosomes and their genetic information impact plant traits, breeding, and evolution.

Cambridge offered him a teaching position after he finished his dissertation, but he chose to join the University of Wisconsin as a postdoctoral fellow. The university at that time had the largest collection of Solanaceae plant family germplasm.

Germplasm is like a treasure chest of seeds, tissues, or cells that contains the genetic information needed to grow new plants.

Swaminathan’s rise at Wisconsin was swift. “Quick, affable, crisply logical, able to juggle multiple lines of inquiry at once, he had a knack for splitting difficult problems into manageable chunks that were each susceptible to the knives of scientific inquiry. His experiments just worked. Articles issued from Swaminathan’s typewriter in an orderly flow and appeared in major journals. Believing that he was destined for a brilliant career, Wisconsin offered him a position as a professor. He turned down the offer, returning to India in 1954 to help his new country,” writes Charles Mann.

Patriotic purpose

Swaminathan never lost track of the purpose of his pursuit of a career in agri science. “Why did I study genetics abroad? It was to produce enough food in India. So, I came back,” he told his biographer RD Iyer.

Agricultural research assignments to match Swaminathan’s stature were almost non-existent in India. He could only be accommodated in a temporary position as assistant botanist at the Central Rice Research Institute in Cuttack—a colonial era institution. There Swaminathan and his team worked on crossing sticky, short-grained Japanese rice, with Indian varieties that were fluffier. That in part led to the creation of India’s most popular rice even today called Sona-Masuri (an Indo-Japanese hybrid extensively trialled at a place called Mahsuri in Malaysia). Soon, Swaminathan was transferred to Delhi to work on wheat.

“Indian farmers had been working with wheat from the Stone Age gradually creating varieties that were suited to the nation’s climate and its culinary preference for the kind of amber-coloured, hard-grain wheat that makes the thin, light-coloured, puffy flatbread called chapati or roti. Like their Mexican counterparts, Indian farmers grew a scatter of different varieties in their fields, planting them sparsely to deter rust [a fungal disease common in crops such as wheat, barley and rye]. At IARI, Swaminathan quickly discovered that these varieties responded to fertilizer so heartily that they lodged—the same problem faced by Borlaug a few years before,” writes Mann.

Now, ‘lodging’ is a phenomenon where plants become so productive that their stalks can’t support the weight of their own grains and get knocked down by wind or rain. It’s like a group of tall, skinny people who try to carry massive backpacks but end up toppling over because of the weight. The grain crops had to be shorter, with a stronger stem.

Kindred spirits

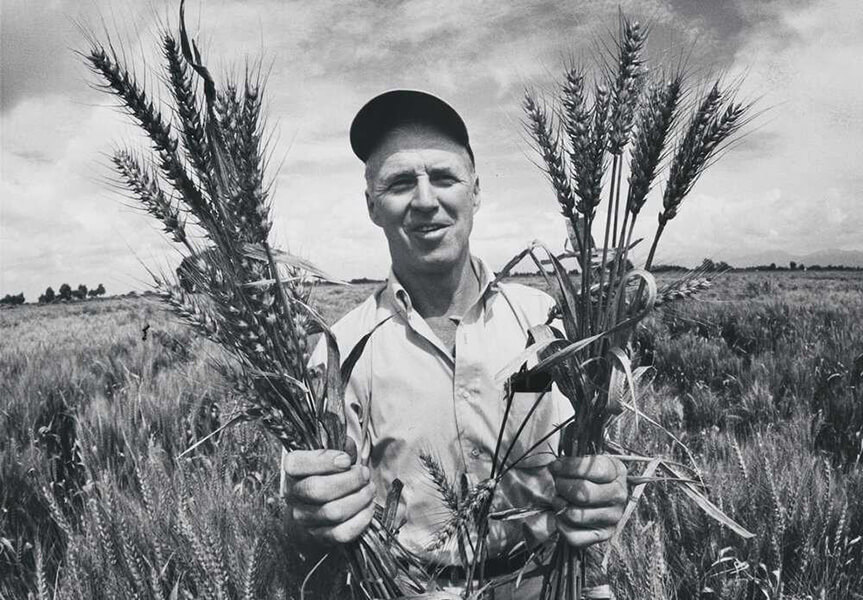

Norman Borlaug was born eleven years before Swaminathan in a poor corn-growing family in Iowa, US. His family had to work so hard as to harvest and shuck 250,000 ears of corn by hand every year. Borlaug, by the standards of boys in his community, was lucky to attend even high school. He earned a PhD in plant pathology and genetics, and like Swaminathan, was driven by the desire to lift people out of poverty.

By a series of accidents, he ended up right after WW2 working in Mexico, on a program established by the Rockefeller Foundation to focus on improving corn production. Like Swaminathan, he had no track record of working on wheat, but was put in charge of it. He embarked on a massive breeding program all by himself, crossing thousands of different varieties of wheat, exposing them to various diseases including the most troublesome–stem rust–and picked the ones that survived. Through this toil of a decade, he created a kind of a super wheat that was not only resistant to stem rust, but also five times more productive than other common varieties.

Like Borlaug, the father of the Green Revolution, Swaminathan, its architect in India was pretty much solving the same problem at around the same time in the mid-1950s with far lesser resources. They weren’t even aware of the similar experiments taking place simultaneously across the world, let alone being personally acquainted.

“In 1955 Swaminathan and his IARI collaborators began taking wheat grain to a small particle accelerator at the Tata Institute in Mumbai. The accelerator sprayed out a beam of neutrons, which slammed into a target and produced gamma rays: ultra-high-energy photons. The researchers blasted wheat kernels with gamma rays for several hours, hoping that the gamma rays would tear into the DNA in the seeds and induce favourable mutations. In twenty-first-century terms, this was like trying to perform surgery with a chainsaw—a hopelessly crude procedure. In mid-twentieth-century terms, it was the most advanced method available. Most of the resultant plants failed to germinate or died quickly—the gamma rays had smashed up their DNA like wrecking balls. A few showed interesting characteristics, but none were short-strawed, at least that first year. Or the second. Or the third. Because Swaminathan couldn’t get enough financial backing to irradiate and grow seeds in large numbers, the odds of success were especially poor. Like Borlaug in Mexico, he was throwing darts at moving targets. Unlike Borlaug, he could throw only a few darts at a time. Still, he saw no other way to proceed,” writes Mann.

A tough path

With Nature unwilling to reveal Her secrets readily, a dejected Swaminathan showed his experimental plot to the Japanese wheat geneticist, Hitoshi Kihara who was visiting India in 1958. Kihara asked Swaminathan to get some dwarf, short stemmed, bigger grain bearing wheat samples developed by the US breeder Orville Vogel.

Vogel’s wheat was of the winter variety that wouldn’t suit Indian conditions. He in turn asked Swaminathan to approach Boralug, then working in Mexico on wheat that could flourish in tropical India. Swaminathan’s 1958 letter to Borlaug in Mexico City never reached.

In 1960, just when Borlaug was hired by the US food giant United Fruit Company to improve banana productivity in Honduras, he was asked by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (UN-FAO) to join an expert group to survey wheat and barley research in North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.

Borlaug was dismayed by the state of agri-science he witnessed everywhere. Most appalling was the approach of Indian wheat breeders who he thought were obsessed with the beauty of the grain rather than increasing yields. The first meeting between Borlaug and Swaminathan was disastrous. “They spoke for about an hour. Neither man seems to have been particularly impressed with the other. One can imagine Swaminathan paying little attention to the blunt, poorly educated foreigner who was trying to tell Indians what to do; Borlaug, for his part, may have seen the other man as the sort of smooth careerist,” says Mann.

Green shoots of a revolution

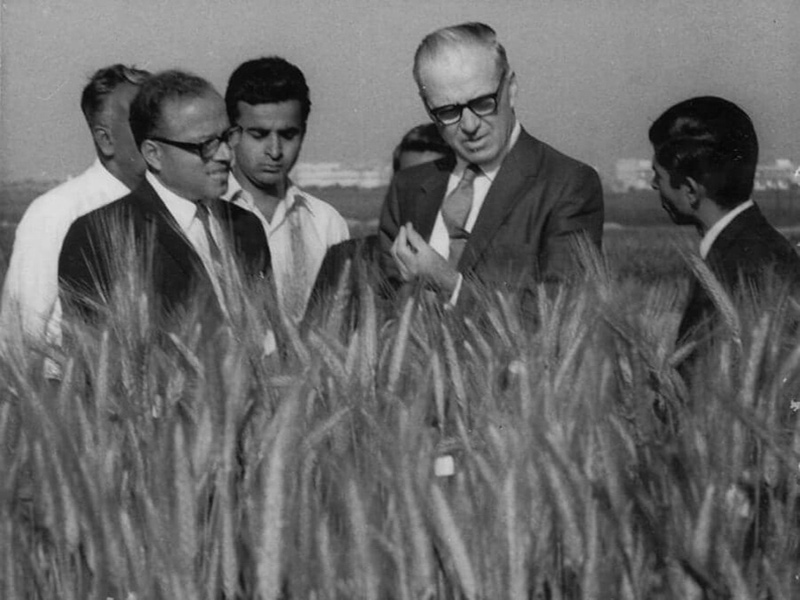

Despite the poor first impressions, Swaminathan’s openness to scientific ideas resulted in extensive trials of Borlaug’s Mexican wheat. In 1963, the two men met again.

Swaminathan took Borlaug and his students on a five-week harvest-time tour of north India and the agri research institutions. “This time the two men hit it off. Borlaug discovered that the man whom he had taken for a time-server had one of the most brilliantly swift agricultural minds. And Swaminathan learned that what he had taken for [Borlaug’s] brusque condescension was a directness and simplicity that he thought almost child-like,” records Mann.

Impressed by Swaminathan’s work, Borlaug sent a consignment of a wide range of seed materials of his two Mexican dwarf wheat varieties, Sonora-64 and Lerma Rojo to India in the following months. The seeds when planted in IARI’s plots responded so well to fertilizers and irrigation that they produced almost three times more than conventional varieties without being afflicted by diseases and pests. Multi-location testing of these wheat varieties in the 1963–64 winter season attested to the potential success at hand.

The breakthrough stage of the Green Revolution had truly begun. Farmers who were introduced to the ‘package’ of high-yielding varieties of seeds, access to fertilizers and good irrigation reported sensational results. In 1964–65, Swaminathan organized 1000 national demonstrations in one-hectare plots in the fields of hundreds of small farmers. The government offered Rs 500 a hectare for the cost of seeds and essential inputs. The results were spectacular; every farmer in Punjab wanted the new wheat seeds but there wasn’t enough of it.

A new beginning

In May 1964, India’s first and longest serving Prime Minister Nehru died. He was replaced by Lal Bahadur Shastri, an Independence leader of impeccable credentials who had a firmer understanding of India’s agrarian reality. Swaminathan’s pleas for greater investment in agri R&D and the farm sector in general found more receptive ears.

Shastri appointed C Subramaniam, a politician from Coimbatore with progressive ideas and a technocratic approach to farming and economic management as the minister for food and agriculture. Subramaniam was the minister for steel in the Nehru cabinet and this new assignment was widely perceived as a political demotion.

Shastri’s slogan ‘Jai Jawan Jai Kisan’, popular to this day, in effect signalled a departure from the Nehruvian course of prioritizing heavy industry over agriculture and national security.

Swaminathan’s suggestion to import 250 tonnes of Mexican semi-dwarf wheat to be planted on 3000 hectares was approved instantly. A bumper crop resulted. Based on this successful experience, Swaminathan and Borlaug pushed for the rapid adoption of Mexican wheat varieties in India, “Swaminathan the scientist became Swaminathan the promoter, undergoing the same transformation that Borlaug himself had earlier gone through in Mexico,” writes RD Iyer, Swaminathan’s biographer.

Even after the Shastri’s death in 1966, his successor Indira Gandhi, continued supporting the new farm programme unburdened by her father’s attachment to the heavy industry-led economic model. In 1968, the Green Revolution had started producing visible results. Wheat production jumped to 17 million tonnes from 12 million tonnes in a single year. “This increase was a revolutionary jump, not an evolutionary one,” says RD Iyer.

Blaming science

It is fashionable for environmentalists and activists to hold Swaminathan, Borlaug and the advances in science that led to the Green Revolution for all the crises of their imagination.

“Borlaug seldom replied directly, though the attacks stung. In private, he told friends that most of the criticism was sheer elitism. Somehow rich environmentalists in the West thought the world was better off if people in poor areas didn’t improve their lives. He had nothing against organic this or that but it was unrealistic to promote it as a solution to hunger in the world of 10 billion. And it was immoral to stand in the way of feeding hungry people,” writes Mann.

Borlaug may not have been too far off the mark. Such critiques, mostly put forth by the elites speaking with the benefit of hindsight and a full-stomach, are as bereft of nuance as India’s granaries in 1947. Addressing the Indian Science Congress at the Banaras Hindu University in 1968, when the Green Revolution’s footprint in India was marginal, Swaminathan said: “Exploitative agriculture offers great possibilities if carried out in a scientific manner, but poses great dangers if carried out with only an immediate profit or production motive. Intensive cultivation of land without conservation of soil fertility and soil structure would lead, ultimately, to the springing up of deserts. Irrigation without arrangements for proper drainage would result in soils getting alkaline or saline. Indiscriminate use of pesticides, fungicides and herbicides could cause adverse changes in biological balance and lead to an increase in the incidence of cancer and other diseases, through the toxic residues present in the grains or other edible parts. Unscientific tapping of groundwater will lead to the rapid exhaustion of this resource left to us through ages of natural farming. The rapid replacement of numerous locally adapted varieties with one-or-two high-yielding strains in large, contiguous areas would result in the spread of serious diseases capable of wiping out entire crops. The initiation of exploitative agriculture without a proper understanding of the various consequences of every one of the changes introduced into traditional agriculture, and without first building up a proper scientific and training base to sustain it, may only lead us, in the long run, to an era of agricultural disaster rather than one of agricultural prosperity.”

To hold our politicians, policymakers and corporations to account on matters as important as food and agriculture based on the scientific wisdom of Indian heroes such as MS Swaminathan would be a better tribute than a campaign to confer them with Bharat Ratna.

This small town in Karnataka is the vegetable nursery of India

Posted on September 27th, 2023

The right socio-economic conditions, availability of trainable talent, clement weather all year-round and a pioneering entrepreneur’s vision to harness it all setting up a sunrise-sector business turns a dozy place into a prosperous hub of startups. This isn’t yet another paean to Bengaluru’s status as the ‘Silicon Valley’ of India. It is the story of a place smack in the geographical centre of Karnataka, 300km to the northwest of Bengaluru called Ranebennur that’s the epicentre of India’s hybrid vegetable seed production.

Since seeds are the most critical and fundamental unit of input in agriculture, it would not be an exaggeration to call such a place ‘startup town’.

Seeds of success

Ranebennur is where India’s largescale, commercial production of hybrid vegetable seeds began in the late 1970s. Today, most major national and multinational agriculture companies from Syngenta to Pioneer to Namdhari have operations in the region. The farmers in this small region produce roughly Rs 500-crore worth of hybrid seeds of vegetables such as tomatoes, chillies, brinjal, okra and assorted gourds.

Such is the economic impact of hybrid seed companies on the local economy that it is common to find homes bearing homage to them. A seed company’s name inscribed in concrete suffixed with the word ‘krupe’ (benevolence) on the forehead of concrete homes painted in bright Vaastu-compliant colours ranging from parrot green to lemon yellow and Barbie pink isn’t a rare sight.

Hybrid hero

All of it is thanks to Manmohan Attavar a pioneering horticulture scientist and entrepreneur who must rank alongside MS Swaminathan and Verghese Kurien in the pantheon of modern India’s agriculture renaissance figures.

Everything on our plate today is a result of hybrid crops from cereals such as rice and wheat to ‘desi’ tomatoes to vegetables such as brinjal and gourds that we consider ‘indigenous’ because of their origins in India.

Hybrid crops are created by crossing two different but related plants to get the best traits of both parents, like two different varieties of tomatoes to create an offspring with desirable traits such as higher yields and resistance to a specific disease.

The science of plenty

Hybrid seeds became commercially important in the early to mid-20th century. The development and commercialization of hybrid seed varieties gained momentum in the 1930s and 1940s, with major advancements in crops like corn, cotton, and vegetables. This led to the widespread adoption of hybrid seeds, which significantly contributed to the Green Revolution and the increase in global agricultural productivity during the mid-20th century.