How 27 techies who wanted to change Indian agri ended up creating a Rs 250-cr organic startup

Posted on August 10th, 2023

Organic dairy firm Akshayakalpa’s 24-acre corporate headquarters-cum-factory near Tiptur, 150km to the west of Bengaluru, gives off the strong vibes of a solemn spiritual ashram.

When steel-tanker milk trucks emitting diesel fumes aren’t lined up at the gate, the thickly wooded entrance, with parijatas in full bloom and countless other aromatics in the flower beds, conjure up the smell of scented vibhuti or sacred ash.

Business such as sales review and training is conducted in squat, circular thatch-roofed huts amidst experimental plots with rows of sugary cherry tomatoes and fern-like carrots.

An unpaved red soil track leads to the source of the rich and healthy smell of manure and ammonia–the gaushala, rather in this case, the R&D centre with about twenty cows reared on organic principles Akshayakalpa wants its partner farmers to follow.

A conversation between farmer and consumer

Among the mostly local employees clad in indigo polo-Ts there are plenty of tourists from Bengaluru even on a weekday. They are a mix of converts and potential converts. It’s a dip of the toe for them. A first-hand experience of the organic food heaven helps spread Akshayakalpa’s organic gospel better than Instagram reels or wordy brochures.

They can caress the cows that wander untethered like deer in a zoo but keen as Labrador pups to befriend strangers and watch them feed on organic Napier grass grown a few metres away. A guided tour of the milk factory and a vegetarian meal at the small canteen with food made entirely from the organic produce grown in the campus follow.

On some days, the dip could turn into immersion, if Shashi Kumar, the stocky 50-year-old co-founder and CEO of Akshayakalpa is around.

Radical chic

Shashi Kumar was a rebel who wanted to ring in a revolution. Softened by the pressure cooker of time burnt on the stove of social entrepreneurship in India’s farm sector, he now appears yogic in his attire and attitude. Clothes in varying fades of blue seem to be his improvisation of the fakir’s ochre. Shashi’s Bhishma-like beard touches the second button, and the unkempt mop of hair reaches beyond the collar of the steel-blue shirt. He can’t quite recall when the shirt was bought, but the pair of denims are decidedly older. For him, the kind consumerism manifested by the hoarding of clothes, and the agricultural crises, have a common link: mindless, unthinking consumption and the methods of production that make it possible.

In 2010, Shashi, an IT professional with a successful career at Wipro, and 27 other friends from a similar background chucked up their jobs with the lofty ambition of “changing” Indian agriculture. They were convinced it was utterly broken. A lot of data and a bit of lived experience showed farming was pretty much unviable as a profession for small farmers in India. Couldn’t Indian farmers become rich, was the question that animated the group.

“The cost of food for the consumer is massively underwritten by State subsidy for inputs such as fertilizers, water and power. The farmers subsidise it further by not properly accounting for their land and labour. The situation is so unsustainable that we soon won’t have people to grow food for us,” says Shashi.

They believed it needed fixing by those who had cracked problems of a higher order. Arrogance was an angel investor in Akshayakalpa.

“IT guys think they are best read, best educated, they know everything about the world. Changing agriculture was easy. That’s the aham [ego] we had. But when we started getting deeper and deeper into farming, we realised that it changed us rather than a bunch of IT guys changing it. The only way to start is to pick a small problem and try to solve it,” says Shashi with a soft, beatific voice, in a south Karnataka accent unsullied by a decade of onsite-ing in the US.

Low cash flow

Not surprisingly, milk is the nucleus of Akshyakalpa’s business. It works with 800 dairy farmers in two close-knit clusters near Tiptur in Karnataka and in a village near Chengalpattu, 80 km from Chennai. Its factory processes 80,000 litres of milk a day producing premium products for Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad markets ranging from milk to ghee that command at least twice the price of popular brands thanks to its organic and antibiotic-free credentials.

“No policy can change the viability of farming. Only the consumers can if they start looking at every aspect of their consumption. They must become more quality conscious and ask questions about who produces their food at what cost, how it gets to them, and how good the food can be if they are paying such a low price. They should go visit a farmer, work with them in the field for a day and share a meal. It’s in their own interest. Today social media glorifies farming and romanticises the farmers so much that it is nowhere near the actual, grim reality,” says Shashi. The purpose of the farm tours is partly to start a much-needed conversation between farmers and consumers.

According to Askshayakalpa, farmers with as little as two-acres who comply with the company’s organic and broader regenerative agricultural practices can make as much as Rs 150,000 a month in about two years of transitioning from conventional methods. Half of the monthly payout goes into the bank account of the female member of a farmer household to ensure that they are adequately compensated for their often-invisible role in running the operations, and also as a safeguard against the hard earned money ending up in liquor shops.

A fourth of its 800 employees consist of field workers and trained agronomists who start work at 6 am on their two-wheelers visiting the 800-odd farmers on a daily basis, addressing their problems, gathering cattle health data and ensuring they stick to organic practices.

Soil is supreme

Shashi’s inspiration for having a strong technical support network for farmers is the work of researchers at the University of California in Davis. “Farmers in the Salinas valley, a big agri belt, don’t have to go anywhere to access new innovations and scientific research. The university’s agri department works out of their fields. Thanks to such coordinated work, almost all farmers have successfully turned organic,” he explains.

Organic or not, dairy is not an easy business to operate, especially at the relatively tiny scale Akshayakalpa operates. Its monthly sales currently exceed Rs 20 crore. More than half of India’s dairy sector is controlled by co-operatives brands such as Amul in Gujarat, Nandini in Karnataka and Mother Dairy in Delhi and many parts of north India. “But our real interest is soil, not milk. Yes, dairy, poultry and coconut generate much-needed, quick cash flow for the farmer. We want to make them part of a larger ecosystem where the cow dung and poultry manure [it has three times more nitrogen that cow dung] substitute inputs like fertilizers and rejuvenate soil, used to make clean domestic fuel, and where beekeeping integrated into the farming system increases pollination,” says Shashi.

Proponents of organic farming say it is entirely misunderstood in India. While produce gets the attention, it is all about soil management. Keeping it nutrient rich and teeming with microflora is at the heart of good organic farming practices.

Organic riches

Shashi grew up in a farming family around Tiptur. His father, still an active farmer at 78, did not have the means to educate his three children. He put young Shashi in his elder brother GN Srinivas Reddy’s care. Reddy was a veterinarian and a well-regarded farm activist influenced by the ideals of Mahatma Gandhi and Vinoba Bhave. “My father wanted me to be an engineer because he knew one who was successful. Engineers were role models, farmers weren’t,” says Shashi.

When Akshayakalpa’s founders travelled the villages to better acquaint themselves with rural realities, they found that most places had turned into retirement homes. There was hardly anyone below the age of 45. Who would produce food for the next generation if the youth desert the farms?

An engineering degree that led to a good life on the US west coast held little charm. Reddy not merely infected his nephew with his own brand of agri- idealism but also became a co-founder of Akshayakalpa. “Before we made our first sale, my uncle went on a 25-day milk-diet to convince himself that our product was good. One of my best memories is the two of us, on the first day of our consumer outreach, convincing eighteen morning joggers in Krishna Rao Park in Bengaluru’s Basavangudi, to become Akshayakalpa subscribers after we gave them a tasting sample,” adds Shashi.

We work with one farmer in a village for a number of years; support him in the transition to organic; and prove to others around that this is a viable model. We run an open-source model. Anyone is free to copy what we do.

Shashi Kumar

Founder and CEO, Akshayakalpa Organic

Can the consumer care?

Despite being in the direct-to-consumer market, Akshayakalpa’s ambitions are modest. At best, it hopes to work with 5000 farmers.

“We work with one farmer in a village for a number of years; support him in the transition to organic; and prove to others around that this is a viable model. We want that farmer to become an inspiration to everyone around. We run an open-source model. Anyone is free to come and copy what we do. In fact, we’d count that as our success,” says Shashi.

Selling expensive organic farm produce in a price conscious market such as India is a hard grind. For example, an Akshayakalpa country egg costs Rs 24 or roughly three times the price of one at the corner shop. Keeping consumer prices reasonable, means taking a hit on margins; lowering the margins for retailers would discourage them from sticking products that require additional care like refrigeration; and competing in the direct-to-consumer market with multiple giants can be brutal and expensive.

By Shashi’s estimation, Akshayakalpa has been on the verge of bankruptcy on six occasions in the 12 years it has been in business. Each time bailed out somehow by his friends who Shashi jokingly calls the 27 fools. Akshayakalpa’s commitment to regenerative farm practices keeping farm income at the centre has won it many admirers. At one of the low points in the business recently, Shashi says he turned to Nitin Kamat, the founder and CEO of Zerodha, the largest stock broking firm in India. “I don’t even know him well, but he was ready to back us,” recalls Shashi.

Last year, Zerodha’s Rainmatter Foundation that focusses on climate action invested in Akshayakalpa.

“What the company is really doing is building water, soil and farm resilience ground up that translates into broader rural resilience. Many of the practices its farmers follow start percolating to their neighbours. If even a third of the dairies in India start operating like Akshayakalpa, it would represent a gigantic change in our agroecology,” says Sameer Shisodia, CEO, Rainmatter Foundation.

The odds in the marketplace seem stacked against a small player such as Akshayakalpa trying to change farming practices and consumer attitudes towards food at once. But it would be good if it succeeded. “Look, it is too big a problem to solve in one lifetime of work. All we can do is try.”

A new Amul-like collective farm movement called FPC to feed India’s future

Posted on August 2nd, 2023

Savita Gadre, 38, is a short, wiry and proud woman. It’s likely her flesh and bones are sinewed by chutzpah. Clad in an aquamarine sari with chunky silver embroidery, Gadre and her colleague Ramshila Kudape, are at a spiritual ashram on the outskirts of Hyderabad to attend the annual Lighthouse Conclave of farmer producer companies (FPC) organised by Samunnati, one of India’s largest private sector financiers in agriculture.

Her home in Temani Khurd village, 25km from Chhindwara in Madhya Pradesh is far away from pretty much everywhere. The trip to Hyderabad would take four instead of the scheduled two days. Gadre’s husband groans on the phone that she’s been away too long neglecting her domestic duties. “Hum BOD [board of directors] hain. Haan ghar se baahar hain, par aapka hi toh naam roshan kar rahe hain [yes, I’m away from home, but I’m only making you proud],” snaps Gadre.

Fruits of success

Gadre and Kudape are directors on the board of an all-women FPC called Chhindwara Organic Farmers Enterprise (COFE).

A farmer producer company or FPC is a social enterprise that’s a hybrid between a cooperative, such as Amul, and a private limited company. An FPC can be formed when 10 or more farmers in a region band together. But it has to be owned and managed by its member-farmers.

COFE has more than 900 women farmer members across 214 predominantly tribal villages. The FPC, founded with the help of an NGO called Srijan which ran a self-help group (SHG) for women, works with farmers who harvest custard apples as forest produce. The women used to lug 25kg of custard apples for 10km to sell them for as little as Rs 50. Now, thanks to the power of collectivisation, they make almost ten times more. COFE processes the custard apple pulp, packages, freezes and sells it to large ice cream companies like Dinshaw’s in Nagpur at Rs 180/kg.

With the experience of operating a cold chain, the company now also sells frozen peas gathered from local women farmers when custard apples aren’t in season. It also has a dal processing plant with a capacity of one tonne a day and supplies organic cotton grown by its members to local ginning mills.

“In the past, we had no identity of our own. When someone came visiting and if my husband or any male member of the family was not at home, my natural response was only to say ghar pe koi nahi hai [there’s no one home] and rush inside. Now we meet buyers in big cities, find new orders and run the whole business by ourselves,” says Gadre. COFE has a turnover of Rs 57 lakh.

Creating 10,000 FPCs such as COFE across the country is a keystone in the government’s plans to increase chronically low small farmer incomes. To develop the FPC movement in the country, the government has made a budgetary allocation of Rs 6,865 crore besides a raft of other schemes to increase the access to money and markets for such companies.

The way out of distress

Nearly 75% of Indian farmers own less than one hectare of land–barely the size of a cricket field. The average monthly income of an Indian farming household, according to the latest government data, is Rs 10,218. That roughly translates to Rs 340 a day, at par with daily wages unskilled labourers in many states get under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA).

“To be a farmer in India is like fighting a ten-headed Ravana. When you think you’ve solved one problem, and nine more crop up. We are up against countless invisible and unpredictable factors. First, there is nature. A whole year’s hard work can be washed away by unseasonal rains at harvest time; water shortage kills us. The global prices may crash or the government might change its policy overnight. There is simply no way a small farmer can win. Indian farmers have a choice. They can collectivise or quit,” says Vilas Shinde, the founder and chairman of Sahyadri Farms, India’s largest FPC based in Nashik with a turnover in excess of Rs 1000 crore.

The Indian agro-economy is pretty much designed to make the smallholder farmer fail. Small farmers buy all their inputs (pesticides, seeds, fertilizers and equipment) at retail rates and sell their output at wholesale prices. They have absolutely no bargaining power when buying or selling. But collectivising offers a way out of the rut.

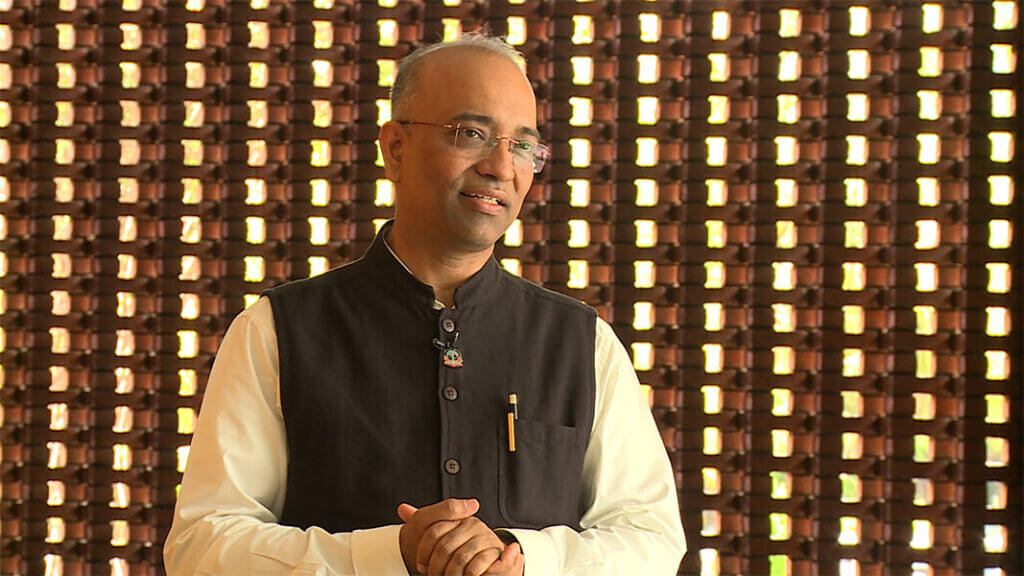

“FPCs enable small farmers to come together and negotiate better prices for their produce. By pooling their resources, they can command better market access, negotiate fair prices, and reduce their dependence on middlemen. This enhances their income and improves economic sustainability,” says Anilkumar SG, CEO, Samunnati, a Chennai-based company that finances FPCs, creates market linkages for them and offers advisory services.

The idea of FPCs was mooted by a government committee headed by economist YK Alagh in 2000. In 2003 the creation of a special class of companies called FPCs was legislated by an amendment to the Company Act, 1956. But a national policy for the promotion of FPCs was put in place only by 2013.

FPCs enable small farmers to come together and negotiate better prices for their produce. By pooling their resources, they command better market access and reduce dependency on middlemen.

Anilkumar SG

Founder and CEO, Samunnati

The taste of Amul

“India has a long history of farmers cooperatives playing an active role in supplying credit and farm inputs and organising marketing. Experience of dairy cooperatives, especially the farmer-owned and operated Amul model in mobilising milk surplus from millions of small holders is a great success story. FPCs can have a similar impact on other segments of farming,” says Ramesh Chand, member Niti Aayog.

Unlike cooperatives, the FPCs are free of government nominees on its board. That helps them evade political interference, be in full control of operations and employ the entrepreneurial energy of the member farmers to the fullest.

FPCs can establish direct market linkages for farmers, enabling them to bypass intermediaries and access larger markets. They can also facilitate value addition activities such as processing, packaging, and branding, which increase the profitability of agricultural produce.

For farmers, being mere suppliers of raw material is a recipe for declining income. Any value addition, even something as simple as sorting and grading of produce, or basic packaging closer to the farm becomes an economic multiplier. By providing access to markets and value-added opportunities, FPCs help small farmers capture a larger share of the value chain.

A richer blend

The Araku Valley in Andhra Pradesh’s northeastern edge bordering Odisha has now become one of the more fashionable coffee supplying regions. The small plantations owned almost entirely by tribal farmers in the low altitude hills of Eastern Ghats still remain untouched by the intensive chemical farming practices of Karnataka’s Kodagu and Chikkamagaluru coffee belts. While the cachet of Araku’s arabica coffee increases among consumers, the tribal farmers who grow them are far from prosperous.

“The lack of awareness is such that our coffee farmers in Araku continue to sell their produce to the middlemen at whatever price they quote,” says Gabbada Chittibabu, a seven-acre coffee farmer in the region who is now a director at an FPC called Manyatorana. The company created in 2019 has more than 1000 members and deals in turmeric and pepper as well.

“Once we organised ourselves as an FPC, we had the scale to process the berries into beans and warehouse it instead of selling at throwaway prices,” says Chittibabu. Manyatorana sells its beans to Tata Coffee (some of it ends up in Starbucks’ blends sold in India) and Blue Tokai. Working with large institutional buyers not only guarantees fair procurement but also improves crop quality based on their feedback and inputs. Manyatorana plans to increase its turnover from the current Rs 3 crore to Rs 15 crore in the next two years as its membership expands.

The fragrance of cooperation

The town of Pushkar in central Rajasthan’s Ajmer district is one of the biggest rose growing regions in the country. Nand Kishor Saini, a 38-year-old rose farmer with a postgraduate degree describes the condition of fellow farmers in the region as pitiable. Saini is the CEO of the Pushkar Rural Agricultural Youth and Employment Producer Company, an FPC set up by an NGO called Krishak Vikas Sansthan that works with more than 500 rose farmers as its shareholders.

Founded in 2015, the company processes the rose and amla its members pool together into value added products such as gulkand, candy and murabba or sweet pickles. With a gulkand processing capacity of 1200 tonnes a year, it sells its products direct to consumers under the brand name Pushkarwala. Procuring at scale for value addition not only allows the company to pay farmers in its network Rs 20/kg more than market rates, but also work with them consistently using modern techniques to increase productivity.

In the Rajput dominated villages in the rose catchment of Pushkar, the social acceptance for women to go out and work remains fairly low. The company works with 300 women to extract the petals, sort and grade them and in the process earn Rs 250-300 a day.

Saini is a relentless travelling salesman setting up stalls at exhibitions across the country organised by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development. Pushkarwala’s differentiator among the hundreds of manufacturers in the region is that its gulkand is made over sixty days instead of the hurried 24 hours others take. “Anyone who tastes our product will become our long-term customer. We have 60-70 permanent buyers especially in south India. We plan to start exporting our products soon,” says Saini.

A capital problem

The other big advantage of FPCs is that they help small farmers access formal credit and financial services, which are often inaccessible to individual farmers. They can negotiate better credit terms, avail group loans, and improve access to agricultural inputs, technology, and infrastructure. This enhances productivity, efficiency, and the overall competitiveness of small farmers. The ability of farmers to collectively manage risks such as price volatility, natural disasters, and market uncertainties makes it feasible for private lenders like Samunnati, public sector banks and institutions like NABARD to channel loans to farmers through the FPCs.

To sell inputs like seeds and fertilizers at discounted price to farmers and procuring produce at a better price from farmers are crucial for them in building trust and engagement among member farmers. For that, timely availability of working capital is critical.

But given that most FPCs in India are fairly young with a low capital base, little formal credit history, collateral, and financial history, they find it difficult to secure loans from traditional financial institutions. “We use a unique underwriting mechanism based on ‘social capital’ and ‘trade capital’. Evaluating the historical relationships with the FPCs’ suppliers and buyers would indicate their performance potential. This makes them eligible for working capital loans to conduct efficient business and strengthen their member engagement,” says Samunnati’s Anilkumar.

Samunnati links up FPCs with large buyers such as ITC, traders, processors and exporters. This helps FPCs eliminate transaction costs by bypassing numerous middlemen.

And after one or two cycles of working capital and repayments, FPCs attain the scale necessary to sustain their operations.

And after one or two cycles of working capital and repayments, FPCs attain the scale necessary to sustain their operations.

Building leadership

Even with policy support, there are many challenges in the path towards creating thousands of Amul-like winners in a wide range of agricultural commodities.

To begin with, there is a lack of awareness among farmers of the benefits and potential of forming FPCs, let alone the many incentives offered by central and state governments. Convincing farmers to unite and collaborate could be even harder. “Farmers need to see tangible benefits from collectivization to be motivated to participate. To win their trust, you must demonstrate the gains quickly and in a transparent manner,” says Sachin Thube, a journalist who founded a successful FPC called Green Up in Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar district.

Most importantly, FPCs need sound governance structures and strong leadership. Several stakeholders in the ecosystem including Sahyadri, Samunnati, NABARD, NGOs and philanthropies such as the Deshpande Foundation run FPC capacity building and leadership development programmes. But that’s no match for the personal drive and determination of farmers such as Savita Gadre in taking charge of their destiny.

The real reasons why tomato is suddenly so expensive in India

Posted on July 17th, 2023

Two rather different sets of rocketry-related headlines have caught India’s attention in recent weeks: India’s second attempt at a moon landing through Chandrayaan 3, and the skyrocketing prices of tomatoes.

It begs the rhetorical question, on the lines often posed by the Western media much to the irritation of Indians: despite accounting for the country’s vastness and the diversity of its challenges, how does India manage to send a two-tonne payload to the moon across 3.85 lakh km while struggling to reliably supply tomatoes from Dewas to Darbhanga, merely 1300 km apart?

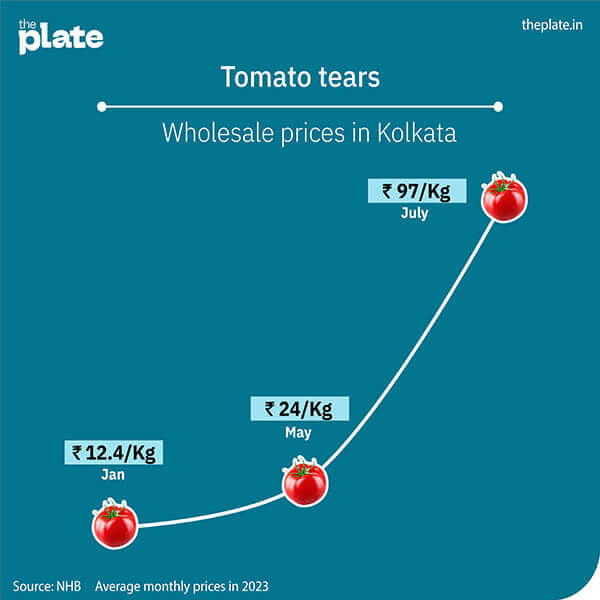

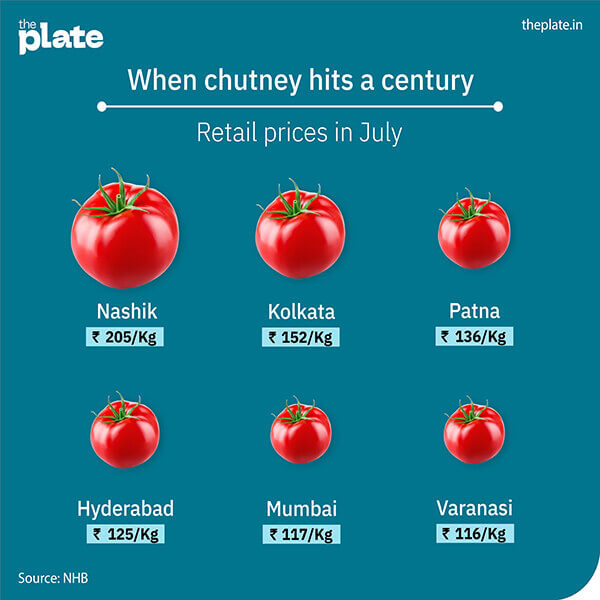

In June and July 2023, the retail price of tomatoes in India rose astronomically above Rs 100/kg. According to the National Horticulture Board’s data, consumers in cities such as Kolkata and Patna need to shell out as much as Rs 150-200. Tomato slices aren’t to be seen in sandwiches and burgers served up by even the big quick service food chains. Your order of pasta arrabbiata is likely to turn the restaurant owner’s face redder than the sauce.

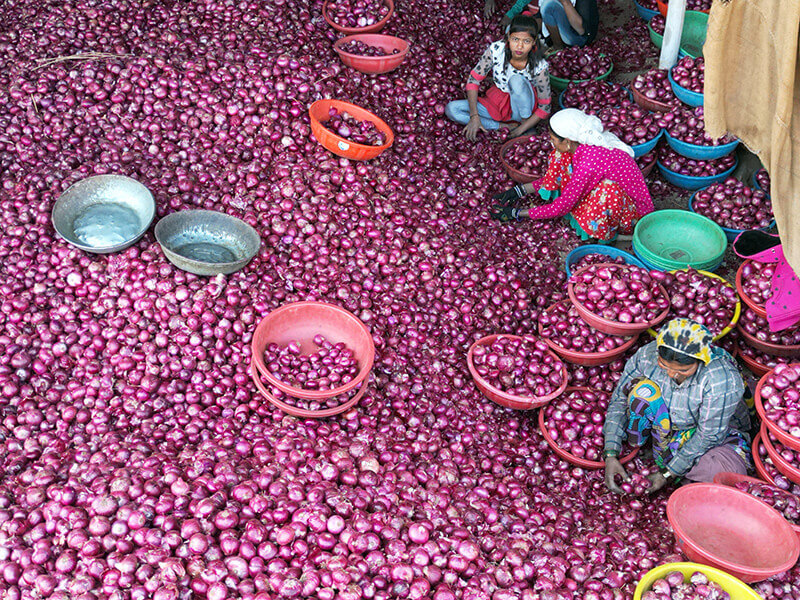

In contrast, just a few months ago in April, angry farmers were dumping tomatoes on the road in protest as their selling price dropped as low as Rs 1-2/kg. It was a repeat of the onion farmers’ plight in February and March.

Feast or famine

India is the world’s second largest producer of fruits and vegetables, including tomatoes. Its output of staple vegetables such as tomato, onion and potatoes (TOP) is significantly higher than domestic demand. Yet, why is India’s fresh food market in a permanent feast-or-famine mode?

Unwilling to miss out on a PR opportunity during a crisis, the Ministry of Consumer affairs on June 30, 2023 launched the ‘Tomato Grand Challenge’ inviting students, research scholars, and the industry to a “hackathon to generate innovative ideas to enhance tomato value chain and ensure its availability at affordable prices”.

Even if the government had no time to read the reports and suggestions of the countless experts it commissioned, it could have called up someone like Vilas Shinde, the chairman of Sahyadri Farms, a Rs 1000 crore farmer producer company (FPC) and one of the largest tomato buyers in the country.

An FPC is like any other company, but wholly owned and operated by farmers in a particular region.

Sahyadri processes 1200 tonnes of tomato a day and manufactures 50% of Kissan ketchup, a brand owned by the global FMCG giant Unilever.

India produces nearly 22 million tonnes of tomatoes and consumes about 20 million tonnes. With paltry exports, there should be no price shock.

“The simple reason for high tomato prices is supply-and-demand principles of economics. In April when the prices went to Rs 1-2/kg, farmers had no motivation to pay attention to their crop. They were not even getting 30% of their production cost as income. They will obviously uproot their tomato plants and try to grow something else. Every agricultural commodity glut in India will be followed by a massive shortage. It’s a vicious cycle for both farmers and consumers,” says Shinde.

Sweet and sour

But it needn’t be so. India is one of the few countries in the world that can grow tomatoes all-year.

India’s tomato production peak occurs between October and April. “The best time for tomatoes pan-India is post February. A day time temperature of 25-32 degrees Celsius is ideal. When heat crosses 38 degrees, the fruit-setting doesn’t happen,” explains AT Sadashiva, a former principal scientist at Indian Institute of Horticulture Sciences (IIHR), Bengaluru, and renowned tomato breeder who has developed several varieties of tomatoes that yield more than 40 tonnes per season in his 30-year-stint as a public sector scientist. Creating a commercially viable new plant variety can take as much as a decade.

Tomato in India is a four-month crop that starts yielding after 60 days of sowing.

“When prices started to crash in March, most farmers made massive losses with their first harvest and didn’t pay any attention to the next two months of yield. There was no point spending on water, pesticides or even harvesting the crop. Our income was barely Rs 1 lakh per crop compared to the usual Rs 2.5-3 lakh. Many didn’t bother sowing the monsoon season tomatoes. They switched to bitter gourd or bottle gourd,” says Ganesh Kadam, a two-acre tomato farmer in Nashik.

During the summer months of May and June, supplies from Narayangaon in Maharastra’s Pune district and Kolar region in the Andhra-Karnataka border form the country’s tomato lifeline.“This year there was the cucumber mosaic virus, and untimely rains that damaged the tomato crop in Kolar,” adds Sadahiva .Excessive heat, rainfall or pest attacks do have local impact on output, but to blame nature alone and explain away a recurring crisis would be a cop out.

No secret sauce

“We have failed to create a milk-like ecosystem for vegetables. Milk goes bad in four hours, tomatoes can last four to five days. But there is no way to store or process tomatoes in or near our mandis. The only solution is the creation of an integrated value chain where farmers grow to demand and convert the surplus into processed products. Farmers have to control this value chain,” says Sahyadri’s Shinde.

India’s tomato productivity at 10 tonnes per acre is considerably below even the global average of 35 tonnes. The country’s much vaunted ‘Kisan Rail’ scheme that hoped to connect producers and consumers through subsidised freight rates and dedicated carriages barely functions.

The first step towards an integrated approach, according to Shinde, must begin with helping farmers achieve yields of 40 tonnes/acre. That would automatically bring the cost of production down.

“The government has to incentivise the private sector to set up tomato processing plants. At Sahyadri, we buy tomatoes for processing when there is a glut. When we start buying in large volumes, the prices stabilise. Even partial-processing of fresh food can extend its life by six months. Tomatoes can be processed to last a couple of years. When farmers are assured of stable prices, they can focus on producing crops that are profitable for them and healthy for consumers,” says Shinde.

India’s tomato processing infrastructure is so poor that it is considerably cheaper to import tomato paste of a better quality from China. Also, a myopic focus on the domestic fresh tomato market comes at the cost of popularising processing-grade tomato varieties among farmers that would fetch them better prices. Such tomatoes need to be sweeter and have lower acidity and water content.

The work of India’s scientists such as Sadashiva and farmer entrepreneurs like Shinde would continue to go to waste until there is a policy that matches their will.

“Tomato prices will come down in November. Consumers will be happy. Farmers will dump their produce on the road, yet again. Uske baad kya [what thereafter]” asks Shinde.

There will be yet another cycle of farmer protest and consumer distress. You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to predict that.

A Kerala entrepreneur’s jackfruit startup that’s fighting India’s diabetes ‘pandemic’

Posted on July 10th, 2023

Startup ideas can strike you if you stare out of the window long enough.

James Joseph, 52, returned to India in 2007 after a stint in the UK and US as a director of executive engagement at Microsoft. He had wangled a deal with the tech giant to work remotely, out of a village near Aluva, a ten-minute drive from the Kochi airport, instead of its Bengaluru office in India, among other things, to be able to give his children a taste of the “slow life”. The arrangement worked out pretty well. Well enough for Joseph to win the firm’s ‘Employee of the Year’ award in 2010.

In 2013, at the goading of fellow Malayali Kris Gopalakrishnan, a co-founder and former CEO of Infosys, Joseph decided to take a year off from work and write a book called God’s Own Office: How One Man Worked for a Global Giant from His Village.

The sight of a giant jackfruit tree in the front yard every time he looked out of the window near his writing desk, and childhood nostalgia for the fruit inspired him to start-up a full-fledged business around it called Jackfruit365.

The company makes flour from raw or unripe jackfruit that can be added to chapati atta or idli and dosa batter without altering the taste while getting the benefits of jackfruit’s high fibre and diabetes-resisting qualities.

A wasted bounty

“Growing up in Kerala you are never too far away from jackfruit. There is an adage that one jackfruit tree in the backyard can extend a person’s life by ten years. It is so plentiful that people don’t even bother to harvest. It just drops to the ground and rots away. The big fruits are now such a nuisance that people are chopping jack trees off,” says Joseph.

While writing the book, he became determined to find a way to put this bounty of nature to more profitable use and give it some good PR.

In India, the home of the jackfruit, the biggest tree-growing fruit in the world, Indians say some terrible things about it, though most don’t know it exists. North Indians hate the ripe fruit for the smell they find unpleasant and, erm, reminiscent of excrement.

It looks frightful too—giant (weighing up to 15 kilos) and spiky. Experts would tell you that you must always run your palm over the fruit before buying one. When the skin is leathery and the spikes blunt, the fruit is ripe for consumption.

My daughter goes to a school with a jack tree that produces slightly sickly fruits with wavy instead of the usual round skin. The tree forms the axis of the communal dining area. Despite five years of familiarity with the tree, and now aged 14, she is still too scared to sup in its shade.

In the south, jackfruit has an exalted status. According to ancient Tamil literature, it is part of the divine troika alongside mango and banana; its wood is used to make the mridangam. Kerala officially declared it the state fruit in 2018. Karnataka’s coastal and hill regions, and the Tumakuru district to the north of Bengaluru jostle for the claim of producing the best jackfruits.

Bengal and Odisha too have a great tradition of jackfruit consumption. Yet, even in these parts, jackfruit gets so little love that we end up wasting almost half our output.

An image makeover

During the writing of the book, Joseph turned into a fulltime jackfruit evangelist coaxing chefs at fancy restaurants in Kerala to include raw jackfruit in innovative ways in a variety of dishes, conning his guests into believing it was some kind of animal protein.

“In India, the typical plate of even those who can afford a nutritious diet, comprises 50% carbohydrates in the form of rice or roti, 25% proteins and vegetables respectively. In fact, vegetables should ideally be 50% of our meal. We are addicted to a carbohydrate dense diet that is often at the root of many lifestyle diseases,” says Joseph.

His idea was if the west can eat Caesar salad, why can’t India get into the habit of eating chakka puzhukku [steamed raw jackfruit tempered with grated coconut, green chillies mustard and garlic], quite popular and still a staple in many parts of Kerala.

“I wanted to rebrand a commodity into a high-value product. If the rich start eating something, the poor too will want to,” adds Joseph.

The neutral-tasting chakka puzukku is essentially a vegetable salad rich in fibre, and a rice substitute that could be had with gravies like fish curry. Joseph’s book had a small chapter on all his experiments to mainstream raw jackfruit including selling burgers made with it.

Out of his admiration for the former Indian President, APJ Abdul Kalam, Joseph made sure to send the first copy of the book in 2014 to him. In November of that year, he got a call from Kalam’s office inviting him for a meeting in Delhi.

Of all the things in the book, Kalam was keen to find out more about Joseph’s work on jackfruit.

The President’s brief

Kalam was convinced a “Second Green Revolution” that matched the IT revolution held the keys to India’s progress. He was intrigued by Joseph’s ideas on making more out of a natural produce going to waste.

Joseph narrated to Kalam his now well-rehearsed script about raw jackfruit having 40% less carbs and two-to-four times more fibre than rice or wheat. “Kalam went silent for about three minutes. I was worried stiff. Then he said, a high-fibre meal always translates into low sugar absorption. That’s a given. There’s one new thing here: most fruits when unripe are acidic. Jackfruit is neutral. But do remember, in India, it’s easier to change religion than food habits. You are an engineer. Find a way to make the whole of India eat green jackfruit; the housewives are the most influential nutritionists, get them on your side. When you do that, I’ll personally come with you to every part of the country and campaign for your idea,” recounts Joseph.

This simple, yet powerful insight became a one-line product brief for Joseph. Could the idea be turned into something like adding iodine unobtrusively to common salt to tackle a public health problem at scale? After all, fortifying wheat flour with jackfruit might benefit not just consumers but also incentivise jackfruit farmers.

The challenge was accepted and within a couple of years, Joseph has found a patented method for dehydrating raw jackfruit and turning that into flour, and most importantly, a flour with the right binding factor that when added to rice batter would not make the dosa stick to the tawa, or a roti to break when mixed with atta. By 2017, the flour branded as Jackfruit 365 was in the market. Sadly, Kalam died in 2015 before Joseph could demonstrate the progress on his challenge.

Building evidence

Not just that, Joseph using his training and experience as an automobile engineer invented a patented device for mechanised, assembly line cutting and extracting of jackfruit pods—the biggest deterrent for even the fruit’s faithful.

“The labour cost of processing jackfruit is very high. Not many people want to handle such a latex-heavy, sticky and gummy fruit. Also, it ripens very fast. The buildup of sugar even in cut raw jackfruit accelerates, so it has to be processed very quickly. I went around the world asking industrial designers to come up with a scalable solution. The structure of jackfruit is different from others like apples. Each fruit has hundreds of bulbs of seed-containing flesh around a stringy core. Everyone gave up, and I had to come up with my own design,” he explains.

From the early days of his evangelism, Joseph was convinced about the anti-diabetic properties of raw jackfruit, but making such claims needed scientific validation and clinical trials.

“While the product was out, we were selling it without telling people the actual reason for buying,” says Joseph.

By 2020, the clinical trial conducted at the government medical college in Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, and its results published in the science journal Nature presented at the annual conference of the American Diabetes Association, allowed Joseph to explicitly make the claim about Jackfruit365 flour helping fight type 2 diabetes in 90 days by lowering blood sugar levels without breaking Indian advertising and food safety regulations.

Type 2, the most common form of diabetes, is a lifelong disease caused by a high level of sugar or glucose in the blood. Insulin is a hormone produced in the pancreas that transports glucose into the body cells where it is stored and later used for energy. With type 2 diabetes, the cells do not respond appropriately to insulin leading to what is known as insulin resistance. As a result, the cells do not get the necessary glucose to release energy.

When sugar cannot enter cells, a high level of it builds up in the blood and the body is unable to use the glucose for energy. This condition called hyperglycaemia leads to the symptoms of type 2 diabetes.

The ticking time-bomb called diabetes

According to a recent Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) study, there are more than 100 million diabetics and 136 million prediabetics in the country. Adults with diabetes have a two-to three-fold increased risk of heart attacks and strokes.

The ability to make a claim for the anti-diabetes qualities of the product, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when physical activity was low and health concerns peaked, turned Jackfruit365 an overnight success on e-commerce platforms such as Amazon.

Joseph’s sales pitch was that adding 30g, or a tablespoon per meal, of jackfruit flour per day to make idli batter or chapati atta could deliver a food item with pharma-grade efficacy.

The sales witnessed a hockey-stick growth. It was the third-biggest selling grocery item on Amazon after Maggi noodles and Tata Salt. According to Joseph, Jackfruit365 clocks sales of more than Rs 1 crore a month just on Amazon with a cumulative customer base of more than 500,000. The National Startup Award in the food processing category in 2020 also helped.

With nearly 1200 grocery and pharmaceutical stores across south India stocking the product, the demand was such that the company had run out of production capacity. It had to pause its marketing campaign. Joseph estimates that the processing capacity of about 1500 jackfruits a day or roughly 15 tonnes needs to go up to 60 tonnes shortly to keep up with demand.

“I wonder how much more popular jackfruit would have been if Dr Kalam was alive to make good his promise to me.” You might have to gaze out of the window to make a guesstimate.

Is ‘cuddly’ Amul the newest ‘crony-capitalist’ from Gujarat curdling India’s milk market?

Posted on May 26th, 2023

The hardcore anti-BJP Opposition politicians seem to have discovered a new bogey business from Gujarat, whose name begins with A, to add to list comprising Ambani and Adani. Amul, one of India’s most beloved brands and a Rs 72,000 crore co-operative giant owned by the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) has become a frequent fly in the unpasteurised milk of Indian politics.

On May 25, 2023, while on an official visit to Singapore and Japan, MK Stalin, the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister released on Twitter his letter to Amit Shah, the Union Home Minister and Minister of Cooperation opposing Amul’s procurement of milk from the northern districts of the state. “Recently, it has come to our notice that Amul has utilised their multi-state co-operative license to install chilling centres and a processing plant in Krishnagiri district and planned to procure milk through FPOs [Farmer Producer Organisations] and SHGs [Self-help Groups] in and around Krishnagiri, Dharmapuri, Vellore, Ranipet, Tirupathur, Kancheepuram and Tiruvallur districts of our state,” he wrote.

Spilling the milk of cooperation

This he argued would create unhealthy competition among milk cooperatives in India and asked Shah to direct Amul to stop all procurement from Tamil Nadu Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation or Aavin’s (its commercial brand) milkshed area.

“It has been the norm in India to let cooperatives thrive without infringing on each other’s milkshed. Such cross procurement goes against the spirit of ‘Operation White Flood’ and will exacerbate problems for consumers given the prevailing milk shortage scenario in the country,” he added.

Fearing a local ‘behemoth’

This comes barely a month after Amul’s decision to sell its fresh milk and curds in Bengaluru was used by the Congress to clabber the electoral milk in Karnataka. Congress and Janata Dal (Secular), then in opposition, claimed that it was part of the Centre’s plans to weaken Karnataka’s own beloved cooperative milk brand Nandini for it to be eventually gobbled up by Amul.

“Milk has clearly become a subject to settle political scores. The large number of farmers engaged in dairy farming makes them a valuable vote bank in any state. Stalin has seen the Congress use the issue cleverly in adjoining Karnataka and could be trying to replicate it,” says Kuldeep Sharma, a veteran dairy technologist who runs a dairy consultancy. Amul already procures milk from two other southern states Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

Milk has clearly become a subject to settle political scores. The large number of farmers engaged in dairy farming makes them a valuable vote bank in any state. Stalin has seen the Congress use the issue cleverly in adjoining Karnataka and could be trying to replicate it.

Kuldeep Sharma

Dairy expert and Founder, Suruchi Consultants

The issue in Karnataka was about Amul expanding its sales while Tamil Nadu is peeved by it procuring directly from the state’s farmers. The common theme here, however, is the portrayal of Amul as a corporate marauder in a cooperative’s cloak.

While Amul’s commercial heft (it is the among the 10 biggest milk processors in the world), the war chest for expansion and pan-India brand recognition lends credibility to such a caricature, it would at the same time be a lazy explanation to shy away from a serious examination of the health of India’s dairy sector and the cooperative movement becoming a pawn in the politics of populism.

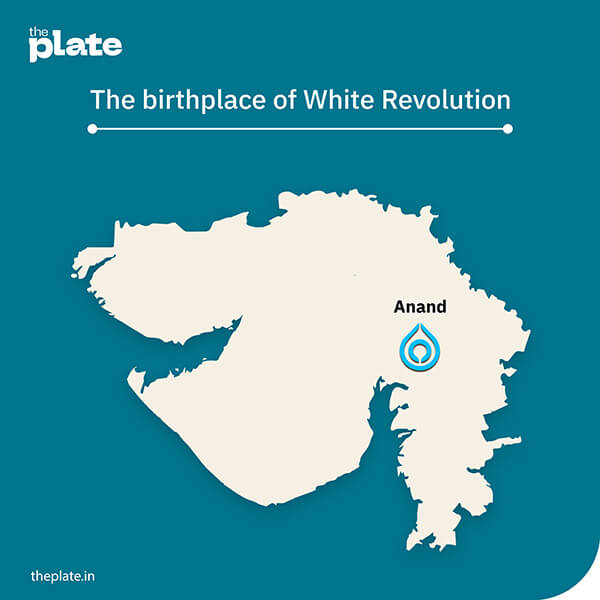

The roots of a revolution

It is instructive to go back a bit in history and understand the birth and success of the cooperative movement.

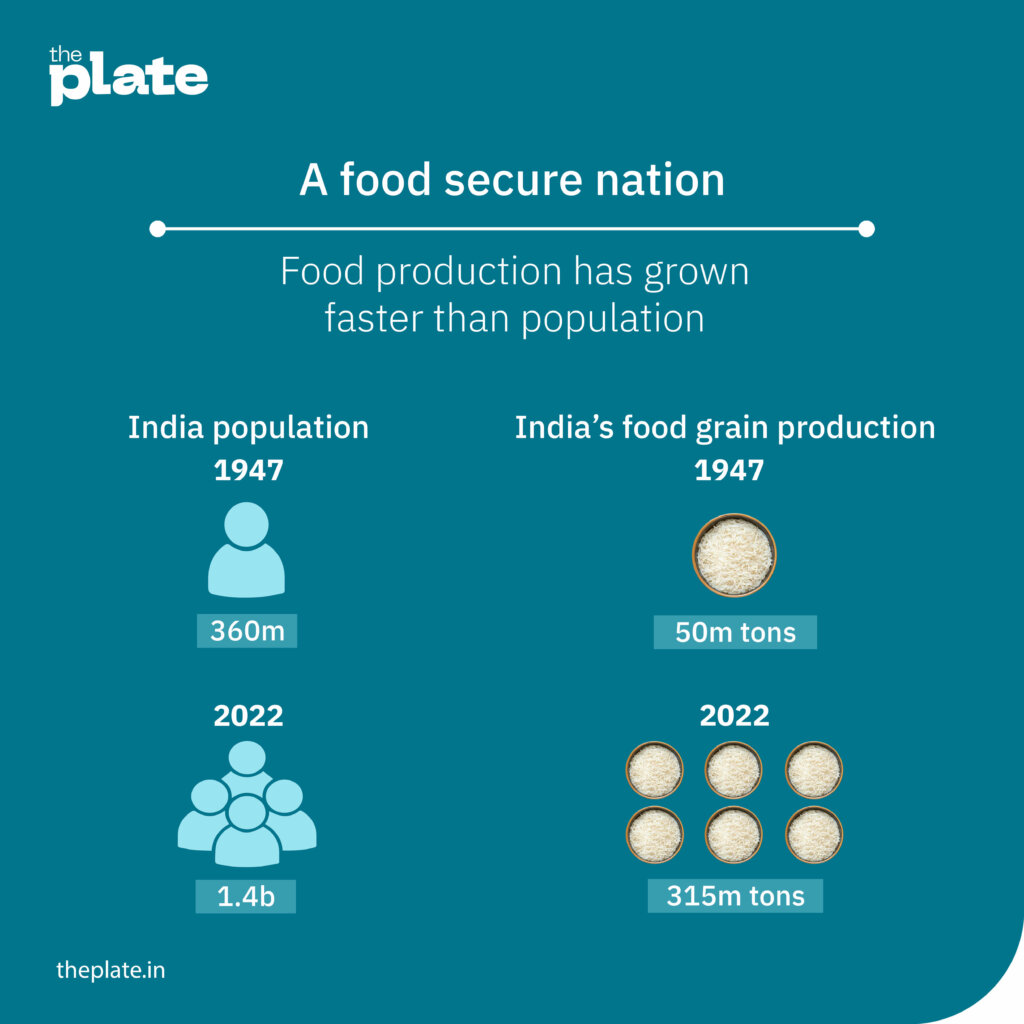

The Green Revolution is considered one of the most important events in the history of modern India. But the gains from the White Revolution are far more spectacular. The Operation Flood or the White Revolution set in motion in 1970 has now made India the largest milk producer in the world.

The 220 million tonnes of milk it produced in 2022 is about 24% of the global output. Indians have access to 440g of milk a day, far more than the recommended daily average of 387g. Milk is by far the most valuable component of Indian agriculture (bigger in value than rice and wheat) and the dairy industry accounts for nearly 5% of the country’s economy.

In 1970, the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) officially launched ‘the billion-litre idea’ with the goal to take India’s dairy industry from a drop to a flood. It was to become the biggest dairy development programme in the world.

Operation Flood would work in a completely decentralised fashion. Milk would be collected by people of the villages; at the district level the dairies would be handled by the district unions; at the state level the marketing would be taken care of by the marketing federations. It was to ensure that the entire value chain remained in the hands of the small farmers. In effect, the White Revolution involved the replication of the “Anand/Amul Model” countrywide.

The White Revolution broadly rung in three fundamental changes. One, it created a nationwide chain of milk-specific cooperatives that could source milk from a network of millions of small farmers owning as few as two or three animals. With access to big volumes of milk, the cooperatives could invest in large processing infrastructure.

They set up small rural collection centres with milk chilling and basic quality check equipment where farmers could sell their output twice a day. The quality checks ensured that farmers’ milk was tested for the fat content, and they were paid fairly in accordance with quality not quantity of milk. At once, it brought in a level of quality assurance the country’s unorganised milk sector was not used to.

Two, the White Revolution introduced new technologies that improved milk productivity. Native Indian cattle breeds such as Sindhi were cross-bred with European Jersey, Brown Swiss and Holstein-Friesian cows. The cross-bred cattle could withstand the hot and tropical Indian conditions, and yet produce more milk. This could only be accomplished by making veterinary services and techniques such as artificial insemination more accessible.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, an extremely perishable produce of farmers was effectively linked to urban markets. All regional cooperatives branded their dairy products—from Amul in Gujarat to Sudha in Bihar, and a national marketing campaign around milk and its benefits as a cheap and accessible source of nutrition helped create sustainable demand.

Thinning milk

But now, some experts contend, lack of attention to breeding programmes and mindless populism has pushed India towards the end-point of the gains from the White Revolution. There are legitimate concerns about India’s milk production plateauing.

“Tamil Nadu complaining about Amul today is like a person crying about theft after leaving their house without a lock. It began with Kerala and is spreading elsewhere. In the guise of subsidising the farmer with higher prices, the cooperatives controlled by the state governments have been subsidising the consumer with cheap milk. It leaves them with no money to focus on cattle breeding R&D. When two pure bred cows—Indian and exotic—are crossed you get higher hybrid vigour from the first generation or F1 hybrids [the best traits of the pure-bred parents. Hardiness from Indian lines and increased productivity from foreign breeds like Jersey]. When you cross the subsequent generations indiscriminately, productivity is bound to get affected. We have simply not paid attention to our native breed stock,” says Rajeshwaran Selvarajan, professor, public policy, Development Management Institute, Patna, who specialises in the dairy sector.

Tamil Nadu complaining about Amul today is like a person crying about theft after leaving their house without a lock. In the guise of subsidising the farmer with higher prices, the cooperatives controlled by the state governments have been subsidising the consumer with cheap milk.

Rajeshwaran Selvarajan

Professor, public Policy, Development Management Institute, Patna

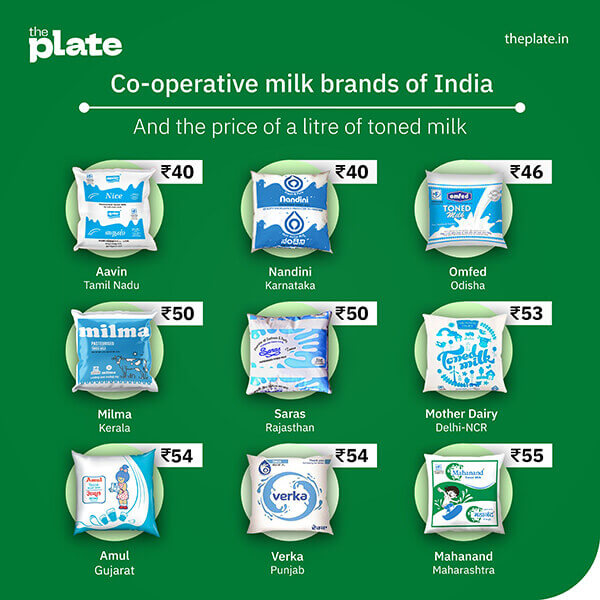

This is how state-level populism has been chipping away at of Indian agriculture’s bright spot. Tamil Nadu’s Aavin for instance procures cow milk from farmers at about Rs 34/litre and the retail price of its standard toned milk is Rs 40/litre (the lowest in the country alongside Karnataka). Keeping consumer prices artificially low results in not just low income for farmers but also throttles the private sector. Private dairies have to pay at least Rs 2 more than the state cooperatives to convince the farmers to sell to them, offer superior agronomy services to retain their loyalty, and then compete in the retail market.

During the recent Karnataka election campaign, Rahul Gandhi promised dairy farmers that the state procurement subsidy for milk would be raised to Rs 7 from Rs 5. Such subsidies amount to more than Rs 5000 crore annually.

The scourge of subsidy

“Subsidy is a cancer that affects the entire industry. It accounts for anywhere between 7-20% of the price of milk across states. How can the private sector compete with such a disadvantage? The states can account for it as a recurring loss and finance it. In fact it is not even going to the farmers, but ending up with consumers. If they had invested that subsidy over a decade in improving productivity and infrastructure, the whole of India’s dairy sector would have benefitted,” said RG Chandramogan, the founder and MD of Hatsun Agro, the largest Indian private sector dairy firm at the Food Conclave organised by the Telangana government recently.

In fact, in states such as Maharashtra, Gujarat and Punjab for where the retail price of a litre of milk is at least Rs 15 more than in Tamil Nadu or Karnataka, the income of farmers too is higher.

So, when Amul procures from Tamil Nadu, the farmers stand to gain at least Rs 2/litre with increased competition. Why is it such a bad thing?

“While its good for the farmers, I can understand the concerns of states like Tamil Nadu. Amul can’t simply use its financial muscle to enter new markets. They should have a dialogue with state cooperatives instead and reassure them on how they will strengthen the local milksheds. That would be in the spirit of cooperation,” says Kuldeep Sharma.

How to feed the world’s most populous country: grow more or eat less?

Posted on May 23rd, 2023

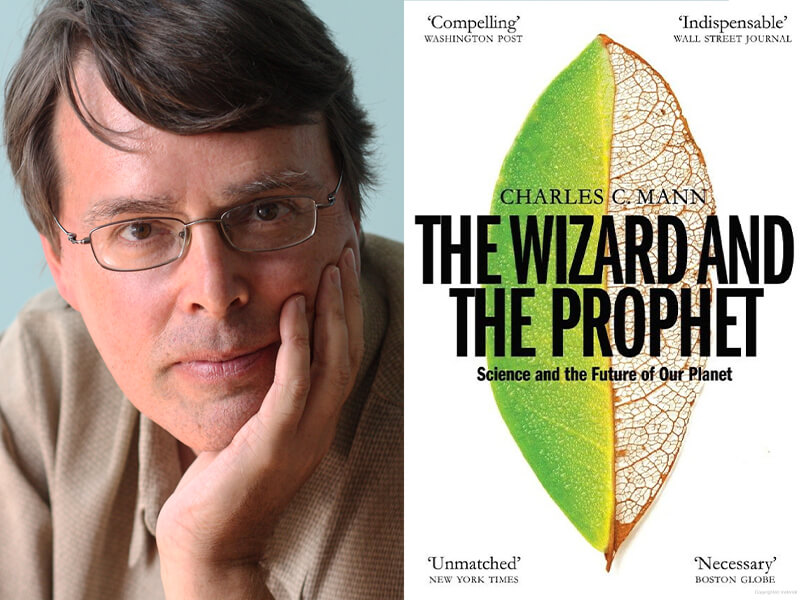

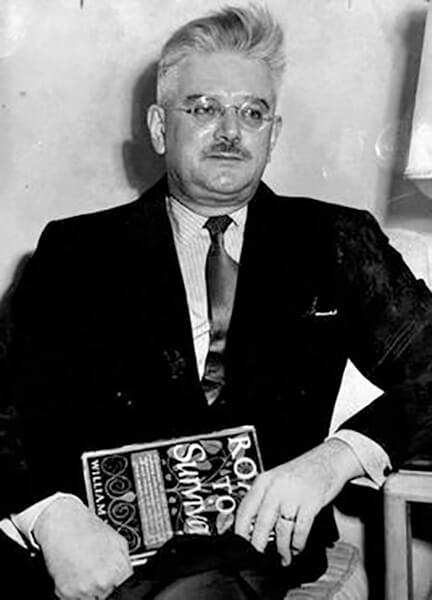

India is now the world’s most populous nation of 1.42 billion surpassing China. In November 2022, the world population touched 8 billion. How to feed 10 billion people by 2050 with lesser natural resources, is a subject that has fascinated award-winning US science journalist and writer Charles C Mann. It was the central question of his 2018 book The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World, examined through the life and work of two contemporaneous American scientists with competing visions, William Vogt and Norman Borlaug. Vogt was the father of modern environmentalism while Borlaug’s role in ushering in the Green Revolution through crops that yielded significantly more may be better known in India.

The Plate’s Managing Editor Aarthi Ramachandran spoke to Mann about these two influential figures and what their prescription to feed the world’s most populous nation might be.

Q1

Who are William Vogt and Norman Borlaug. Why did you decide to write about them?

I’m a science journalist and I’ve been reporting on these issues and talking to scientists, activists and politicians about agricultural research and feeding the world for 30-40 years now.

Over time, I realised that the kind of answers I was hearing to my questions fell into two broad camps, each of which I realised was associated with people who lived and died in the 20th century, that most people hadn’t heard of, but were profoundly important.

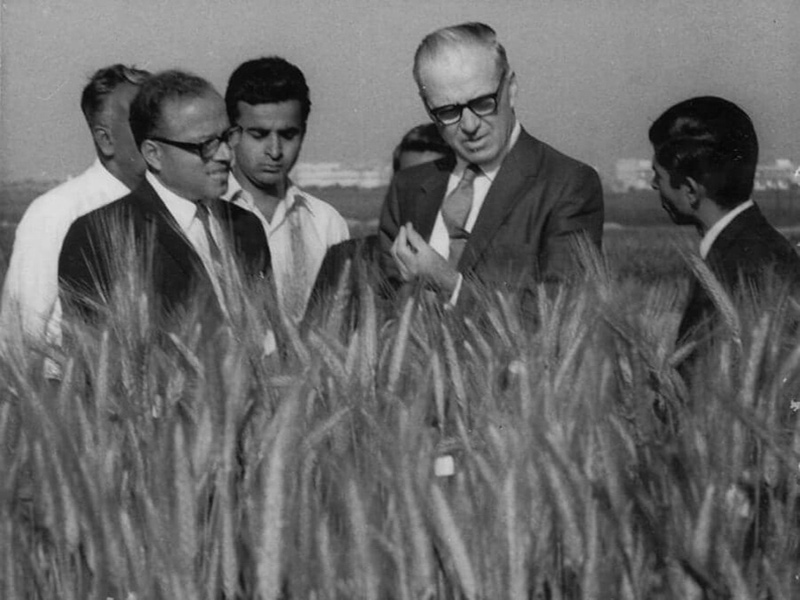

One of them was Norman Borlaug. He is the chief figure associated with the Green Revolution, which is the combination of advanced seeds, irrigation and high throughput fertiliser that doubled or even tripled cereal production and had an enormous impact on world history. In fact, particularly on Indian history, because India is where the central part of the Green Revolution occurred.

He was an inspirational figure who told people you could use the tools of science and technology to produce more to give everybody as much as they want.

At the same time, I would hear from another set of people that this approach was fundamentally flawed. They said this is crazy because the world has planetary limits and a carrying capacity that we simply cannot surpass. I began to wonder, where did this idea come from?

And I realised that there is a guy even more obscure called William Vogt, who wrote out in 1948 the founding ideas of what has become the modern environmental movement, which is the only successful ideology to emerge from the 20th century.

I thought, this is extraordinary because these two people were working at the same place, at the same time and came to such radically different conclusions.

And they collided. The collision between people who are following them, knowingly or unknowingly, characterised much of what we hear in debate about environmental issues today. I thought that seemed like something worth learning more about, maybe telling other people about.

Q2

Why the title, ‘The Wizard and the Prophet’?

I initially wanted to call it ‘The Engineer and the Druid’ because Borlaug had an engineering mentality. For everything there had to be a practical solution. The world just consists of atoms. So, engineers think, let’s rearrange those atoms in a way that’s maximally profitable to everybody.

Vogt had a much more spiritual idea, that there are these webs of interactions of life that were as close to something sacred as he knew, and that we had to respect this.

But my publisher said nobody knows what a druid is. I disagreed. We went out to a Barnes Noble bookstore and my publisher asked the clerk for a book called ‘The Engineer and the Druid’. And the clerk looked at him and asked, “What’s the Druid?” So I decided to rename them ‘The Wizard’ and ‘The Prophet’. We are always talking about technology as wizardry. The Prophet, because Vogt was a person who was decrying both capitalism and the way that we were living.

Q3

How were their ideas and visions for the world ‘duelling’, as the tagline of your book says?

The striking thing is both were born poor, into the lower strata of US society. Borlaug was born in 1914 in a very poor part of Iowa. His family had to work enormously hard all the time. They grew corn and he would have to harvest and shuck 250,000 ears of corn by hand every year and then go to school.

He was lucky to go to high school. He then went on to college and even to graduate school, which is an extraordinary thing for a person in that time and place. He grew up thinking of agriculture as terrible but necessary drudgery.

He wanted to lift people out of poverty. And by a series of coincidences, he ended up right after WW2 working in Mexico, on a program established by the Rockefeller Foundation to focus on maize. But there was a tiny branch of this program that tried to breed wheat that was resistant to a disease called stem rust, and he was put in charge of it.

He had no money. He didn’t speak Spanish. He’d never been outside the United States. He’d never worked with wheat. He’d never done any kind of plant breeding. Borlaug was just wildly unqualified for the job. But he was enormously hard working. He decided to do a massive breeding program just all by himself, where he got thousands and thousands of different varieties and crossed them, exposed them to stem rust, and took the ones that survived. Through this toil of a decade, he created a kind of a super wheat that was not only resistant to stem rust, but also almost five times more productive than the previously known varieties.

It was really a remarkable accomplishment. Borlaug did many things that were against what was in the textbooks, but he didn’t know it. It turned out, partly by sheer luck, the textbooks were wrong. And it was a signal event in the history of humankind.

Vogt was born in 1902 in a poor part of Long Island in New York. He saw the natural world around him flattened by a deluge of houses, people, roads and cars. He was afflicted by polio when he was young. He walked with a cane and a limp and braces for all of his life.

Vogt became an ornithologist during the Great Depression. And by great luck managed to get a job in Peru where his task was to maximise the population of cormorant birds on the islands off the country’s coast.

The little-known islands off the coast of Peru called the Chincha Islands have been the home for thousands of years to cormorants. Roosting there in great numbers over thousands of years, they left enormous deposits of excrement which were mined by Asian slaves in the 19th century and became the world’s first high intensity fertiliser.

In fact, the whole idea that you could buy fertiliser in a store and then sprinkle it on the land and create an enormous productivity boost came from this mountain of bird excrement in the Chincha Islands. There was a global market for this natural fertiliser. But by the 1930s the bird poop deposits were going down and they wanted him to, as he put it, “augment the increment of excrement”.

There he came to a conclusion that was startling and important: that in some sense it was impossible. And the reason was the birds eat fish that were in the enormous fisheries off the coast of Peru. But fisheries are controlled by the temperature of the water.

There are cold water fisheries during La Nina years. When the waters get warm in the El Nino years, the fish move out from the shore and they move so far that the cormorants can’t reach them. When that happens, of course, the fish production is very low and the cormorants die.

So, he realised that if you do increase the number of cormorants to augment the increment of excrement, they will die in the next El Nino year. It was Vogt’s great contribution to say, wait a minute, this isn’t just true for islands off the coast of Peru, but for most, if not all, natural ecosystems.

They have limits on how much they can produce. And if you surpass those limits, you destroy them. This, he argued, was true for the earth as a whole. In 1948, he wrote The Road To Survival. It’s what I call the first, modern, we’re-all-going-to-hell book.

It is striking that Vogt was working in Latin America and indeed later in Mexico, at the same time as Bolraug. Bolraug looked at the problems and the people and said we need to give them more tools.

Vogt looked at the exact same landscape in the exact same conditions, and he said, the land is being over exploited. We need to pay attention to it. And this led to a clash between them that has continued to the present day between people who are focused on producing more and consuming less.

Q4

What are the hard and soft paths—that Borlaug and Vogt respectively advocated—that you write about? Can you give us some examples of how these ideas are relevant today?

This is a term I’ve borrowed from people who look at water. There’s probably no disagreement that the most pressing environmental problem is securing an adequate supply of fresh water for everyone.

The hard path is to say what we need to increase the supply. That involves things like mining aquifers that are not yet exploited, or desalination. The idea is you make more using technology. That’s the wizards’ answer.

The prophets will find it crazy. To begin with, this requires enormous amounts of energy. In addition, the salt from desalination is toxic. It’s extremely hard to get rid of. They are in the soft path. They say humans use water in crazily wasteful ways. Phoenix in the US’ extremely dry Southwest is full of golf courses. Hectares of grass is grown and soaked with water in very hot weather.

You can go into the central part of California which is a big agricultural area and see people growing rice in giant pools of water. That water is transported from mountains thousands of miles away to evaporate in the desert. So, the prophets would say, don’t grow rice or play golf in the desert.

Q5

India is perhaps the country where the Green Revolution had the most significant impact. One of the central figures of that from an Indian perspective is Dr MS Swaminathan. How do you see his role, and what were the Borlaug-Swaminathan interactions like?

Swaminathan was a critically important partner for Borlaug whose name is far less known than it should be. He is a really remarkable man in every way: a super good scientist, part of that first generation post-Independence; did first-rate work in the West and came back to India because he wanted to help his new country. He understood India in a way that Borlaug didn’t.

The development model in India associated with Nehru saw agriculture as stagnant. There were a huge number of people just mired in their farms and barely producing. The trick was to get them off of the farm so that they could be industrial workers and make steel and cement and all the things necessary for industrialised society.

So, the budgets for development were heavily skewed towards the industrial sector with the result that the agricultural sector really did lag. And this came to a head in the 1960s with the famine in Bihar.

There’s been a lot of historiography or argument about how bad it was, but it was clearly very real and also something that was used for political purposes. It was very embarrassing for the Congress government. They didn’t want to admit that there was a famine. Then there was a very paternalistic view of the US government, which was trying to make India a kind of client state.

The US wanted to trumpet the amount of aid it gave to India. So, from their point of view, they want to maximise the impression of the problem, while the Indian government wanted to minimise it. Borlaug came with wheat that he had developed in Mexico that he believed was a universal type of grain, and he brought it to India.

But Swaminathan did something incredible to it which Borlaug never really understood. He took Borlaug’s wheat, which was red and therefore dark in a way that was not good for chapatis and roti, and bred it to be white like Indian wheat.

It is important to produce food that people want. Swaminathan understood that. He adapted it to Indian conditions, gave it an Indian name, and was enormously successful.

Q6

If Vogt had to come up with a prescription for India today what would it look like? We know what Borlaug would have said because we’ve lived through his ideas here in India.

Well, first, he would say that there are too many people, not just in India, but everywhere. The benign view of this argument is that you’re just making it so difficult for natural systems to function because they have to function at the top of their carrying capacity. The less benign part of this is that you force down the population of black and brown people around the world. This led to, particularly in China, to tens of millions of forced sterilisations, forced abortions which were terrible.

You would like to think that Vogt would have learned from this. I think the answer that a modern-day person would give is if you want to reduce the pressure on natural systems, empower women. It seems to be a universal human characteristic that women, you know, don’t want to have 127 kids!

They could then run their own businesses, be teachers or do the things that anybody else would want to. The Vogtian thing would be to make that possible, to make sure that you have good schools, and adequate health care. So, I would say his answer would be to have good social policies.

A brief history of India’s White Revolution: the story of remarkable individuals and collective spirit

Posted on May 17th, 2023

1942

Colonial exploitation

In 1942-43, several Britishers living in Bombay suddenly fell sick. Investigations into the matter revealed that the chief cause was the milk they were consuming. A sample of milk was sent to UK for testing. The test result read: “The milk of Bombay is more polluted than the gutter water of London.” Consequently, the British government was forced to come up with a plan to improve the quality of milk coming into the city.

The search for a reliable source of milk in large volumes led the Bombay government to Kaira district (now called Kheda in Gujarat, but then part of Bombay Presidency) some 330 kilometres to the north.

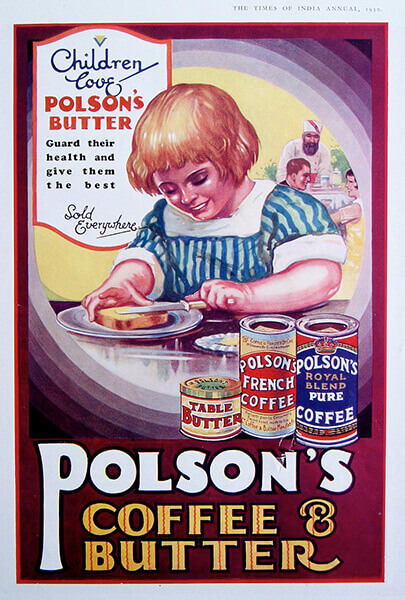

By then Kaira already had the reputation of being a milk hub of sorts. Around 1895, an Englishman had started a butter factory some 15km north of Anand in this district. A German had also set up a casein factory nearby. Casein is the milk protein which in the early 20th century was used to make plastic. Casein plastic was used to make products like buttons and fountain pens. In 1926, a Parsi businessman Pestonjee Edulji had built a factory to make butter that was sold under the brand name Polson in the region. Polson was to be a household name before another brand from Anand killed it off.

The Bombay government asked Polson if it could supply milk every day to the city from Kaira across 330km. Something like this hadn’t been done in India. Polson pasteurised the milk in its plant and sent it in cans wrapped in gunny bags drenched in cold water. With this pioneering experiment of shipping liquid milk across such long distances in 1945 was born the Bombay Milk Scheme.

Polson had the monopoly on milk supply; Bombay offered a large readymade market for the farmers’ produce; and consumers had access to better quality. It was to be a win-win for all involved. Except it wasn’t.

The farmers of Kaira increased production to such an extent that the district had already become the largest and best-known milk producer in the entire region.

But the farmers very soon realised that only a fraction of the consumer price reached them as Polson and its contractors pocketed most of the money.

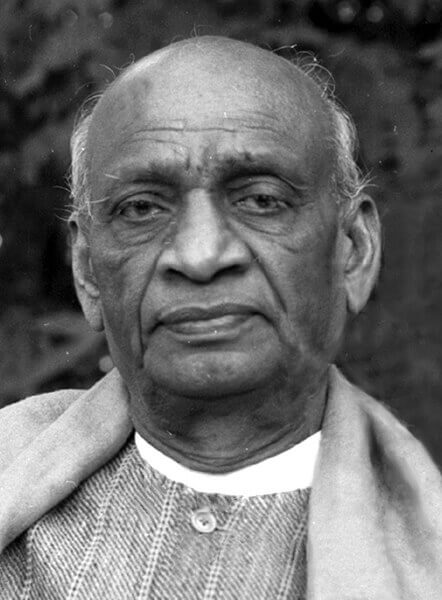

Kaira’s farmers recounted their story of exploitation to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel who belonged to the same region. Patel’s answer was that the farmers had to be in control of the entire milk value chain—from production to marketing. He asked dairy farmers to organise milk cooperatives, which would give them control over the resources they generated. He assigned Morarji Desai, his deputy, to coordinate the effort. Desai identified a young freedom fighter and the vice chairman of the Kaira District Congress Committee, Tribhuvandas Patel, to head the cooperative.

Despite the formation of farmer groups, the problem of exploitation persisted. Polson would somehow find a way to pay farmers less. It would complain of flies in the milk or pay them less on account of lower fat content in the milk.

1945

Battle cry

When Tribhuvandas Patel and farmers went back to Sardar Patel, his battle cry was “Remove Polson”. But to do that the entire dairy movement in the district had to be united and, above all, they had to own their dairies. Since it was 1945, he warned the farmers that the British would not take such a move kindly.

1946

An Indian milk co-op is born

By January 1946, the farmers had decided to take on Polson and the government. They decided not to sell any milk to Polson and that a cooperative would be set up in every village of Kaira. A union of these cooperatives headquartered in Anand would process and market the milk. BMS rejected the proposal. The farmers of Kaira went on a strike for 15 days. They were happy to pour the milk on the streets rather than sell a drop to Polson. The strike crippled Polson and BMS went bust.

The British government relented hoping that bunch of Indian buffalo farmers and their leaders in Gandhi caps didn’t know a thing about dairy farming and would come crawling back to the old arrangement when their experiment inevitably bombed.

Through 1946, Tribhuvandas patel walked from village to village persuading farmers of Kaira to form cooperative milk societies. By December 1946, the Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers Union Limited (KDCMPUL), the mother of Amul was born. India’s biggest market, Bombay, was now directly linked to the farmers of Kaira.

In 1946, a young engineer called Verghese Kurien was selected by the British government in India to study in Western universities and gain a Master’s degree. Kurien belonged to a wealthy and privileged Kerala Syrian Christian family. His grand uncle John Matthai was to become the independent India’s first Railway Minister. While young Kurien was interested in metallurgy and nuclear physics, he was chosen for a Government of India’s agriculture ministry sponsored degree at Michigan State University, then considered the best place for dairy research in the world.

1949

The unwilling young man

While Kurien had earned a master’s degree in metallurgy with some mandatory courses on dairy technology, upon his return to India, he was posted in Anand as a researcher in the Government India creamery in 1949. Disinterested in his job, Kurien was looking for the nearest exit.

1950

An offer that couldn’t be refused

The Kaira Cooperative’s plant was in the same campus as Kurien’s office. In his spare time, and there was plenty of it, he frequently helped fix the outdated 1910-era machinery it used.

After a routine repair job, Kurien told Tribhuvandas to scrap the rusty plant and build a new one if the cooperative had to have any chance of survival. Tribhivandas took up the challenge of arranging the Rs 40,000 it took for the new plant and asked Kurien to build it. It was merely an unpaid side gig for Kurien. When the plant was built and Kurien’s resignation from the government job finally accepted, Tribhuvandas offered him the job of the general manager at KDCMPUL in 1950. It would be tempting to say the rest is history. It wasn’t as easy.

1952

Bootstrapping a revolution

By 1952, against all odds, KDCMPUL was supplying 20,000 litres of milk compared to 2000 litres in 1948. Anand’s farmers were supplying milk to Bombay’s consumers in insulated railway vans.

The success of Kaira cooperative movement was by now in no doubt. But a problem of demand-and-supply cropped up as the Kaira-Bombay market linkage grew stronger. Buffaloes produced twice the milk in winters than summers. There was no market for the excess winter milk, while there was no way to store it for supply during the lean summer months.

The only solution was to set up a processing plant to convert the extra milk into products like butter and milk powder. While the Western world knew how to turn cow milk into powder, there was no way to make buffalo milk into reconstitutable powder.

Thankfully, Kurien’s mate at Michigan State University and ace dairy technologist Harichand Dalaya was at hand. Dalaya hailed from a prosperous Yadav family in Uttar Pradesh that ran a successful dairy business in Karachi with 300-odd Sindhi cows. The family had enough money to send him to Michigan before it was forced to wind up operations in Karachi post Partition. Dalaya invented a way to spray dry buffalo milk into powder when every single dairy technologist in the world had thought it impossible.

1955

Scaling up

Dalaya’s invention paved the way for India’s first milk powder and butter plant that was inaugurated by Prime Minster Jawaharlal Nehru on October 31, 1955, the birth anniversary of Sardar Patel.

1956

Amul the brand is born

By 1956, Kurien realised that Kaira Cooperative’s increased milk productivity needed an even bigger market, that in turn needed better branding and marketing. A chemist at the Cooperative came up with the name Amul. It was a derivative of the Sanskrit word ‘amulya’ that meant ‘priceless’. It not just symbolised the pride of swadeshi production, was short and catchy and could be an easy acronym for Anand Milk Union Limited. In 1957 Kaira Cooperative registered the brand ‘Amul’ that would soon become one of India’s best-known brands.

1964

For an Anand everywhere

On October 31,1964 when PM Lal Bahadur Shastri visited Anand on yet another birth anniversary of Sardar Patel, he asked Kurien to replicate the Anand model across India. Despite the support of the PM, the plan failed to take off due to bureaucratic meddling and turf wars within the government.

1965

The National Dairy Development board

To fulfil the wishes of the PM, and in national interest, Kurien convinced the Kaira Cooperative that it should create The National Dairy Development Board without central government funding in 1965.

1966

An advertising icon in born

In 1966, Amul upped its advertising game. It hired an agency called the Advertising and Sales Promotion Company (ASP) with a mandate to knock Polson off from its perch as Bombay’s top butter brand. ASP’s art director Eustace Fernandes created the iconic Amul girl to take on Polson’s ‘butter girl’. It had also launched several milk powder, butter, condensed milk, cheese and baby food.

1970

A billion litre dream

In July 1970, NDDB officially launched ‘the billion-litre idea’ with the goal to take India’s dairy industry from a drop to a flood. It was to become the biggest dairy development programme in the world.

Operation Flood would work in a completely decentralised fashion. Milk would be collected by people of the villages; at the district level the dairies would be handled by the district unions; at the state level the marketing would be taken care of by the marketing federations. It was to ensure that the entire value chain remained in the hands of the small farmers.

1976

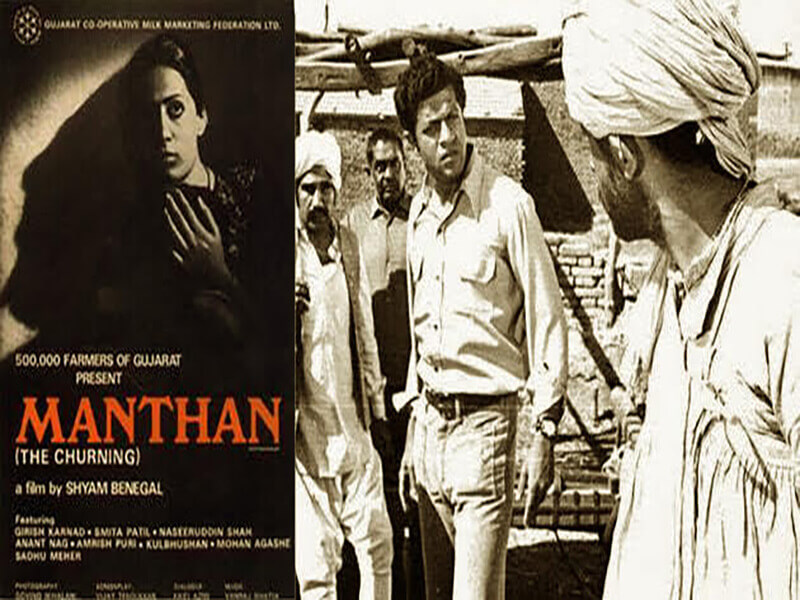

Real life in reel

Manthan, a film based on Kurien’s efforts to collectivise Gujarat’s dairy farmers and the Operation Flood, directed by Shyam Benegal was released. Made on a shoestring budget of Rs 10 lakh funded entirely by the dairy farmers of Gujarat who contributed a rupee each.

The film starred young actors like Smita Patil, Girish Karnad, Naseeruddin Shah and Anant Nag and won several awards.

But Amul used it as part of its sales pitch to farmers to join the cooperative movement and drive home the message of the economic and social benefits of the cooperation.

1981

The White Revolution gathers steam

The second phase of Operation Flood from 1981 to 1985. It was implemented with the seed capital from European countries and a Rs 200 crore World Bank loan. During this period, the number of milksheds increased from 18 to 136. Moreover, 290 urban markets increased the outlets for milk produced. By the end of this phase, a self-sustaining system of 43,000 village cooperatives covering 4.25 million milk producers was well established. Milk powder production increased from 22,000 tonnes in the pre-Operation Flood year to 140,000 tons by 1989. Direct marketing of milk by producers’ cooperatives increased by several million litres a day.

1985

Investments in technology

The third phase of Operation Flood, which lasted from 1985 to 1996, added 30,000 new dairy cooperatives to the 42,000 existing societies. The number of women members and women’s dairy cooperative societies increased considerably. This phase focused on assisting unions to expand and strengthen their procurement and marketing infrastructure to manage the increasing volumes of milk. Veterinary health-care services, feed and artificial insemination services for cooperative members were extended. Animal health and nutrition was the big focus area.

1998

Becoming the world leader

In 1998, India overtook the US to become the largest milk producer in the world.

The same year, the World Bank published a report on the impact of dairy development in India and looked at its own contribution to this. The audit revealed that on the Rs 200 crore the World Bank invested in Operation Flood, the net return into India’s rural economy was a massive Rs 24,000 crore each year over a period of ten years. Certainly no other development programme, either before or since, has matched this remarkable input-output ratio.

2023

Challenges ahead