Making millets mighty again

Posted on May 2nd, 2023

Millets are easy to miss. In the endless e-commerce aisles, or indeed your diet. But these tiny grains—the word ‘millet’ conjures up the image of a miniature version of something like ‘islet’ or ‘droplet’—were once big, very big in India, much of Asia and Africa.

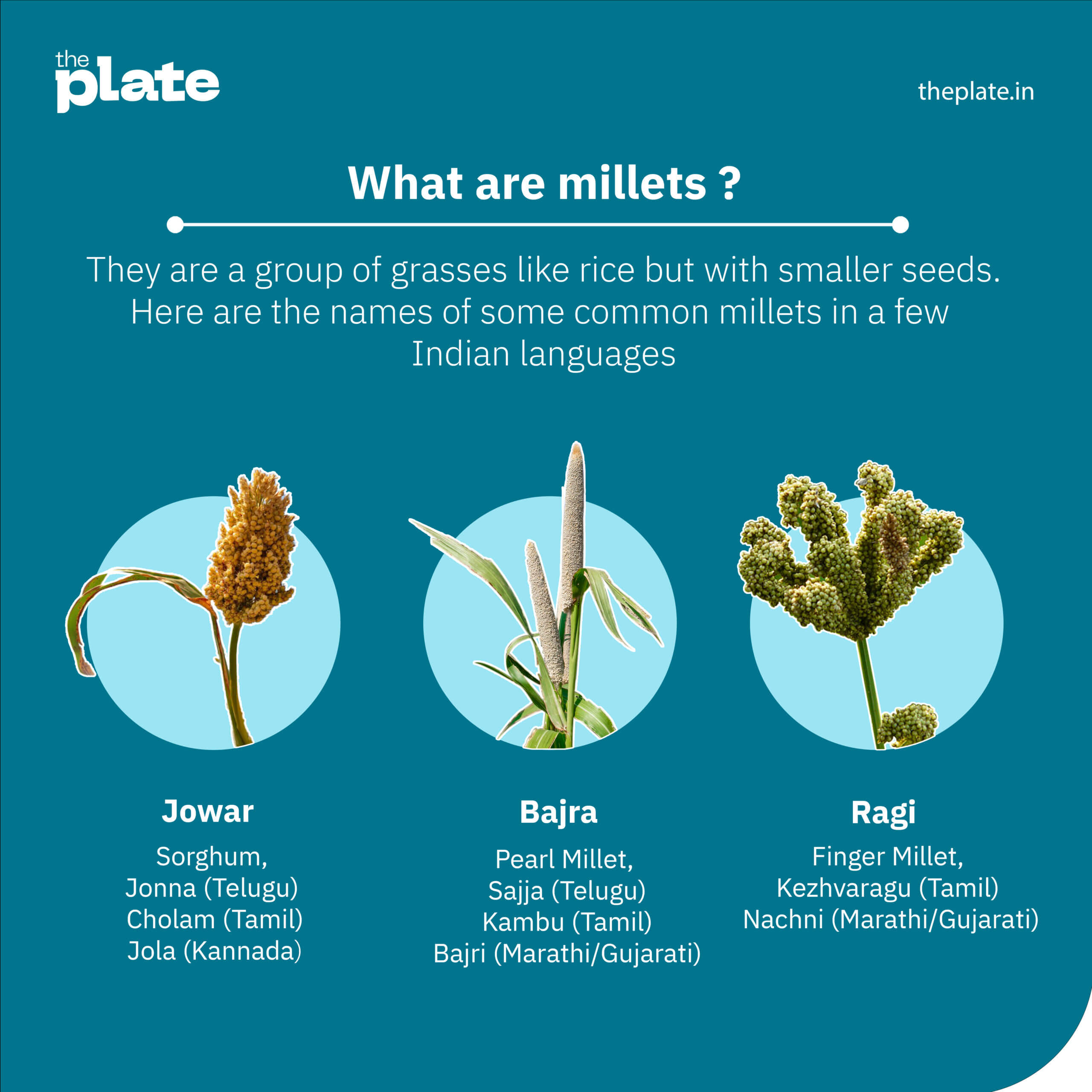

In fact, they were the first grains to have been domesticated, or in other words, cultivated at a large scale for human consumption, predating rice, wheat and corn, the three biggest cereal crops of the world today. But the Europeans, who colonised these lands, were brought up on a wheat-based diet. They failed to make sense of the small-sized staple grains the natives ate. They called them “small grains”. A grainlet when milled. The millet!

The name stuck. Millets were India’s staple going as far back as the Indus Valley Civilization in 3000 BC. But thanks to the colonial hangover, they were, until recently officially called “small” or “minor” grains.

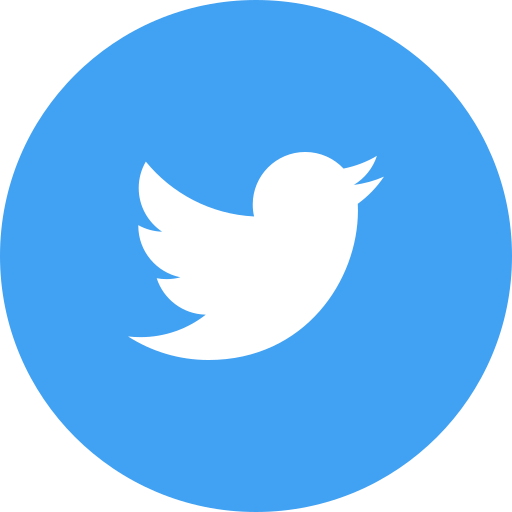

Today, unless you are a food activist attending organic food fests, are diabetic, or suffer from assorted lifestyle diseases, it’s unlikely you’ll encounter the brown, yellow, red, tan, or sometimes just polished white small grains like ragi (finger millet), jowar (sorghum) and bajra (pearl millet). Of course, there’s plenty of social media buzz as the United Nations (UN) has declared 2023 the ‘International Year of Millets’ (IYOM) thanks to a push sponsored by India.

WTH are millets?

The reason UN is championing millets is because they truly fit the label ‘smart foods’. The global campaign for them is built around the theme that they are good for you, the planet, and the farmer.

Millets are a group of hardy, small-grained cereals that can adapt well to hostile conditions. They don’t mind hot, dry regions with low rainfall or poor quality soil unlike rice and wheat. Ragi for instance is so adaptable that it can grow prolifically in the high Himalayan terrain of Pithoragarh and Uttarkashi in Uttarakhand, the arid regions of Gujarat and the rocky and dry rainfed deccan plateau. Ragi’s resilience is such that it can grow in rocky regions with as little as an inch of topsoil, and needs an annual rainfall of barely 450 mm compared to 1200-2000 mm for rice. Millets are also the lifeline of small and marginal farmers in rainfed areas without access to irrigation or abundant groundwater.

India, historically, has had a long tradition of millet consumption. A kanji or porridge made of ragi, a pinkish-brown grain the size of mustard, was once the first weaning food for kids and the meal that even those on the death bed were given because it is easy on the digestive system. Ragi balls, called mudde, accompanied by a runny meat or vegetable gravy remain a rural south Karnataka staple. Rotis or versions of it like bhakri made of millets such as jowar, bajra and ragi are not uncommon in India’s small towns and villages.

The powergrain

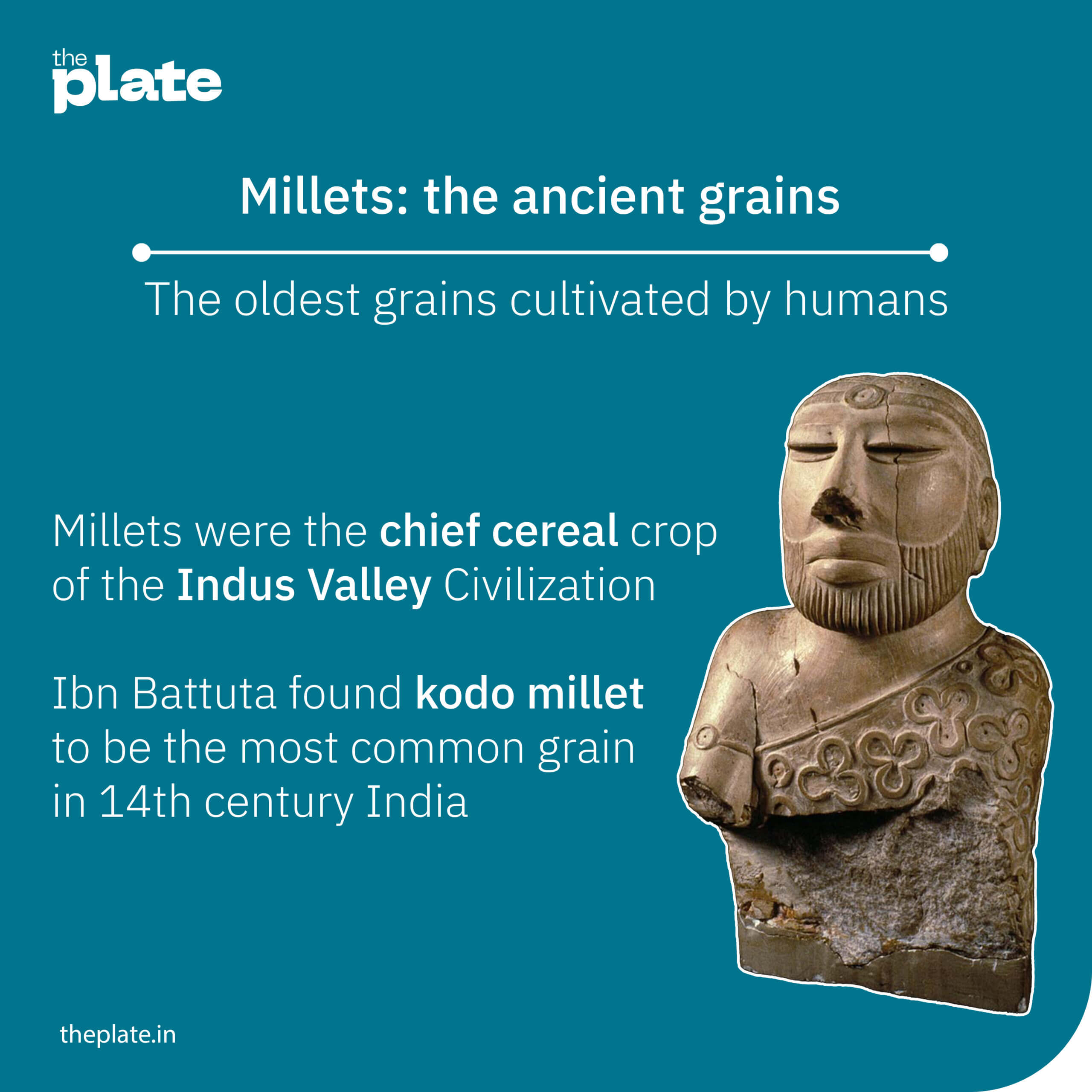

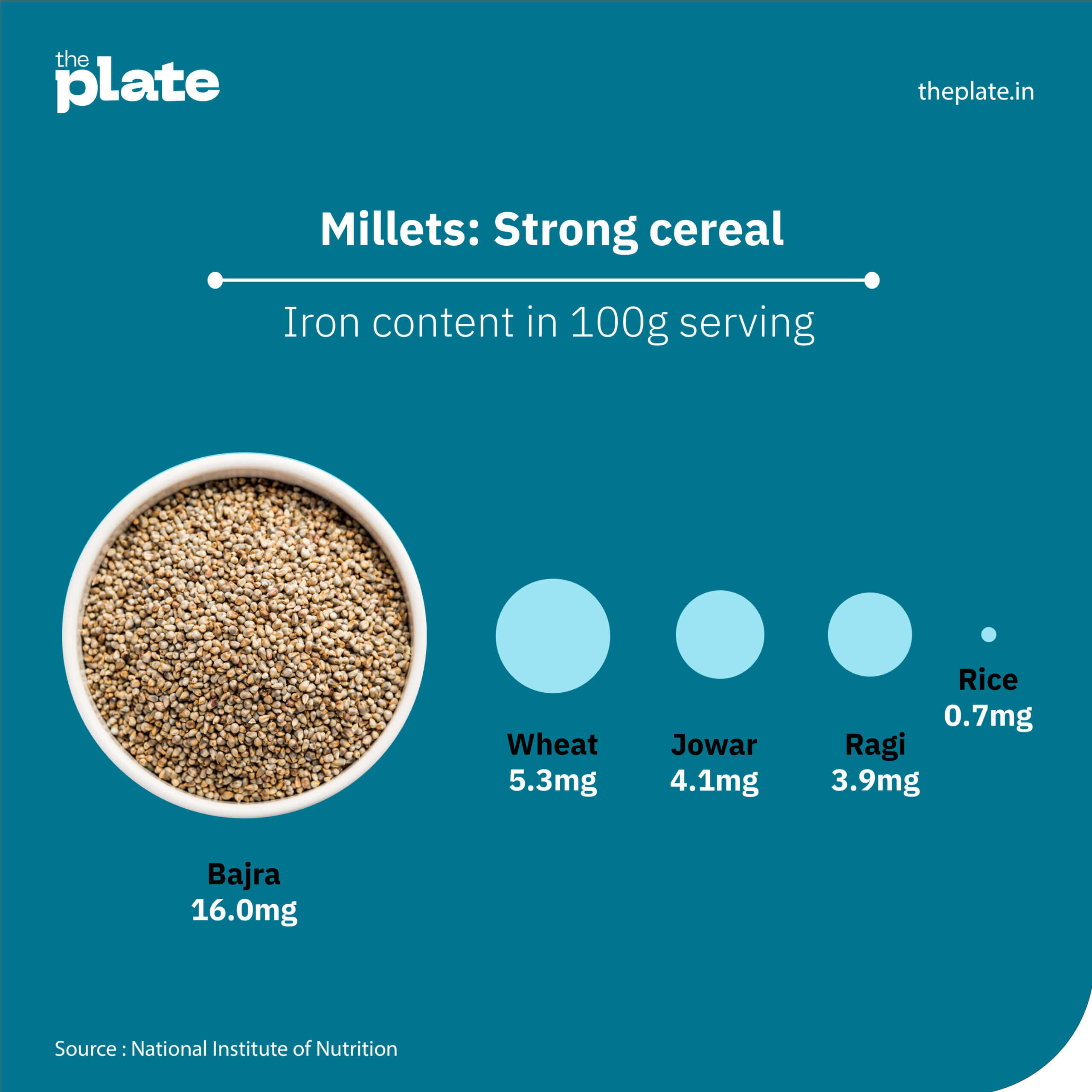

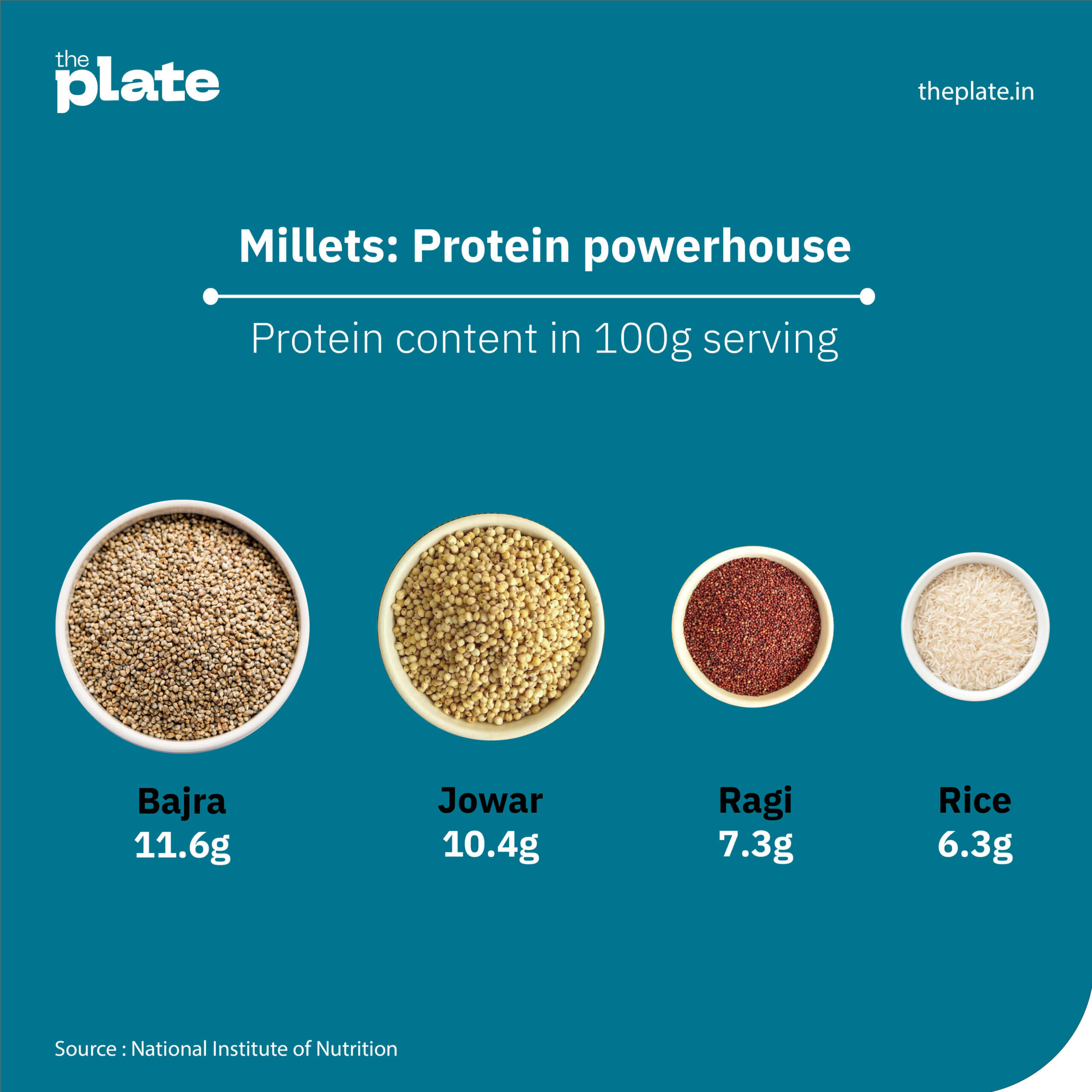

In terms of health and nutrition millets pack a punch. They are miles ahead of rice and wheat in their protein, fiber, mineral and micro-nutrient content. Ragi has 30 times more calcium than rice; bajra, three times more iron than wheat and four times more dietary fibre than rice; and jowar about one-and-a-half times more protein than rice.

A 2017 report on the nutritional and health benefits of millets by the Indian Institute of Millets Research (IIMR) found that millets help in combating cardiovascular and lifestyle diseases such as obesity and diabetes, lower the risk of cancer and even offer protection against several degenerative diseases such as metabolic syndrome and Parkinson’s disease. They are vital in tackling ‘hidden hunger’ too. It’s the condition where access to food isn’t a problem. but the food is high in carbohydrates (like rice, sugar and potatoes) but low in nutrients.

Given the overwhelming case for millets, India has been making a push for them, mostly through marketing and communication campaigns for a while, with limited success. In the run up to the UN’s programme, India had declared 2018 as ‘National Year of Millets’. Despite all the publicity and Prime Minister Narendra Modi talking about millets on his ‘Man Ki Baat’ radio address, there hasn’t been much change in either the consumption or production of millets.

India produces roughly 18 million tonnes of millets—more than any other country. But to put it in perspective, they are a droplet in our annual grain basket of 315 million tonnes (rice 128 million tonnes, wheat 110 million tonnes, according to the latest government estimates of production).

So is the government doing anything to mark this year beyond publicity campaigns, catchy slogans and special millet lunches for Members of Parliament and visiting foreign dignitaries? Is it possible to achieve a quantum jump in the production and consumption of millets within the country even as it gears up to project itself as a global millets hub and promote the nutritional and ecological benefits of millets to the world?

The answers to these questions lie in understanding millets better, their disappearance from Indian plates and how governments, both at the Centre and in the states, view millets now.

A dramatic fall

As mentioned, the importance of millets historically can be gauged by the fact they find mention through history in several ancient texts as well as songs and folklore. Millets were the quintessential food of the common people.

Their fall began in the colonial period. Between 1870 and 1939, enabled by new canal networks, the area under agriculture in India grew by 60%. “The main gainers from this expansion were the food crops, wheat, rice, and pulses, and the industrial crops, cotton, jute, sugarcane, oilseeds, and groundnuts….By comparison, millets (jowar, bajra, and ragi) did not gain much land,” writes Tirthankar Roy in the book, The Economic History of India.

The use of millets plummeted further after Independence. From the mid-1960s, India embarked on the Green Revolution to attain food self-sufficiency. The dramatic increase in the production of wheat and rice under the Green Revolution came at the cost of other crops such as millets.

We need to work towards a situation where greater awareness brings about a change in people’s perceptions about millets. It would be best if demand drives supply.

Ashok Dalwai

CEO, National Rainfed Area Authority

With a combination of better yielding varieties of rice and wheat, fertiliser subsidy, irrigation facilities and assured procurement for the public distribution system (PDS), farmers as well as consumers took to rice and wheat— dubbed ‘fine cereals’— in a big way. For farmers, there was greater income security and profitability in growing rice and wheat; consumers preference too shifted wholesale. Rice and wheat were inexpensive, accessible and aspirational foods. They became national staples.

Green’s Revolution’s KO punch

Millets today continue to be viewed as the food of the poor and those engaged in hard physical labour. Moreover, there is a taste bias against millets. The neutral taste and easy texture of rice and wheat compared to the nutty flavour and coarser feel of millets has accelerated the shift towards the former. Until 1961, Indians consumed an average of 33 kg of millets. In less than five decades it was down to a mere 4 kg.

With falling demand, farmers continued their switch to more remunerative crops. In 1965, at the beginning of the Green Revolution, millets were grown in 37 million hectares. Today it is down by almost 60% at barely 15 million hectares. The Story of Millets, a publication brought out by the Karnataka Agriculture Department and IIMR in 2018, notes that dryland farmers previously growing millets now preferred soyabean, cotton and maize, more profitable and in demand. Only in Rajasthan, a bajra-growing state, which has the highest area under millet cultivation, acreage has remained steady due to the climatic limitations of making a switch.

The one positive in all of this is that while acreage of millets has gone down, productivity has increased by a stunning 288% between 1950-55 and 2015-2020, indicating that there has been adoption of higher yielding varieties and hybrids. The total quantity of millets grown in India through this period has, however, continued to hover between 15-18 million tonnes.

The road back

With India championing the cause of millets globally, is there any likelihood of this situation changing? The Central government is making all the right noises—a positive sign given the neglect of millets in the last five decades—yet it has done little to promote more millet growing by farmers.

For example, in a written Lok Sabha reply on December 21, 2022, the Central government reiterated that it planned to increase the production of millets in the country under the National Food Security Mission (NFSM). Then, at a pre-launch IYOM event in New Delhi, agriculture minister Narendra Singh Tomar spoke of the need to ‘diversify the food basket’ under the PDS to include millets for improved nutrition of children and women. Yet, Budget 2023 made no additional allocations for millets despite the spotlight that IYOM has brought. In her Budget speech, Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman went as far as coming up with a special name for millets, calling them ‘Shree Anna’ or divine grains, but no further.

This is not the first time that millets have been rebranded. The government had renamed them as ‘nutri cereals’ in 2018 – moving them up from the category of ‘coarse grains’ – and also created a ‘sub-mission’ for them under the NFSM. As part of this scheme, growing millets is now encouraged in 212 districts in 14 states. Also, under the National Food Security Act of 2013 families are provided rice, wheat and coarse grains (including millets) at Rs 3, Rs 2 and Re 1 per kg respectively. Although these moves are well intentioned, the procurement and distribution of millets through this scheme has remained tardy. Similarly, while there have been significant hikes in the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for major millets, jowar, bajra and ragi, experts say it means little in the absence of assured procurement of the grains.

Can we invest 25% of what we invested on research in rice and wheat during the Green Revolution on millets in the next ten years?

Arabinda Padhee

Principal Secretary, Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment, Odisha

State governments in comparison have fared somewhat better at promoting millets. Karnataka and Odisha stand out for offering economic incentives to farmers for growing millets as well as for making them avalabile to consumers by bringing them into the PDS. There are also noteworthy efforts by Chhattisgarh (which has revived kodo and little millet cultivation in the tribal-dominated Dindori district) and Uttarakhand which has decided to introduce millets into the PDS.

Odisha has, in fact, been the biggest success story in millet cultivation and adoption. Starting 2017-18, the Odisha Millets Mission (OMM) has managed to scale up operations from 7 districts covering 30 blocks to 19 districts and 143 blocks. By 2024, the programme is slated to cover 177 blocks in 30 districts. Not only has it assured procurement of ragi for its PDS, but has also been able to take millets to pre-school children by introducing ragi or mandua ladoos to them in two districts. Odisha’s procurement of ragi shot up from nearly 1,800 tonnes (18,000 quintals) in 2019-20 to about 32,300 tonnes (3.23 lakh quintals) in 2021-22. What makes the programme unique is its focus on promoting the daily consumption of millets at a household level.

Farmer friendly

The Odisha model may have lessons to offer India in terms of both addressing the production as well as consumption ends of the effort to bring millets back. According to Sabyasachi Das, National Co-ordinator of Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network and Director WASSAN, which designed the OMM, the programme works along four important parameters: production and productivity, local consumption, processing and value addition. “In OMM, the inclusion of millets in the PDS was part of the design,” he says, emphasising the need for India’s initiatives around IYOM to generate the “right kind of conversations” around the nutritional aspect of millet as a priority. “We need to speak not just about millet cookies and cakes, but how can Indians have two millet meals a week,” he says.

Policymakers too believe it is time for India to transition from “food security” to the more meaningful paradigm of “nutritional security”. “We need to ask whether there is a good rationale to move beyond ‘food security’ [which has worked well for us]. Millets fit both the consumption as well as production criteria in this transition to nutritional security and sustainable agriculture,” says Ashok Dalwai, CEO, National Rainfed Area Authority, who also chairs the Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income.

According to Dalwai, India needs to draw lessons from the Green Revolution and offer millets the same kind of support that was offered to rice and wheat earlier. “The farmer is an economic animal. He will make an intercrop comparison — of millet with paddy and wheat,” he says, noting that the yield for paddy was about 3.1 tonnes/hectare, whereas it was 1.1 tonnes/hectare for jowar. Assured procurement and integration of millets in the PDS as well as a number of other measures such as increasing yields and improving shelf life would be necessary to make this transition from food to nutritional security. “It needs at least 10 years,” he adds.

According to Arabinda Padhee, Principal Secretary in the Odisha government’s Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment, India will need sustained research and consumer awareness campaigns to bring about the change needed for a large-scale adoption of millets. “Can we invest 25% of what we invested on research in rice and wheat during the Green Revolution on millets in the next ten years?” he asks, pointing to the kind of long-term commitment that would be required from both Central and state governments.

It is perhaps in this context that we need to view events such as IYOM which are aimed at generating awareness and bringing about a change of mindsets. “We need to work towards a situation where greater awareness brings about a change in people’s perceptions about millets. It would be best if demand drives supply,” says Dalwai.

Finally, unless consumers are convinced that millets are good for them, and farmers find sustained profitability in growing them, the ‘good-for-planet’ part of the millet sales pitch will remain good on paper only.

Forget Bournvita, India has a far bigger sugar addiction problem

Posted on April 28th, 2023

The recent controversy around Cadbury forcing social media influencer Revant Himatsingka to take down a video on high sugar levels in the popular malted beverage mix Bournvita has shone a spotlight on branded food labelling and what exactly do the processed foods we consume contain.

It is also a good time to consider a more fundamental question related to India’s food and agriculture policy: why is India addicted to sugar, and why the government is determined to push us down this unhealthy path?

Does India have a sugar problem?

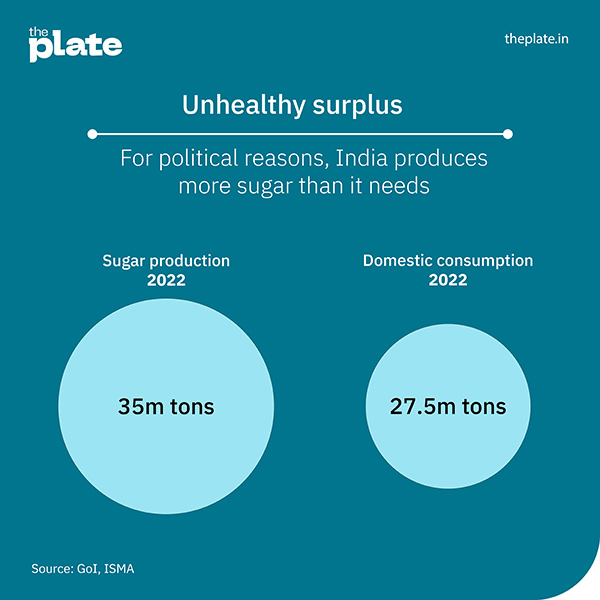

Yes. In a nutshell: India produces way more sugar than it needs, using up precious water and financial resources; and as a result, Indians end up eating more sugar than is healthy. In recent years, it has been trying to use a lot of its excess sugar to produce ethanol. India blends its petrol with 10% ethanol to save a bit of the foreign exchange used for importing oil. But the use of sugarcane as fuel makes it attractive for farmers to grow more of a crop that isn’t very good for the environment, India’s agri economy, or the health of Indians.

India is the world’s largest producer of sugar. In 2022 it produced nearly 36 million tonnes. It is the second largest consumer with a domestic demand of roughly 26-27 million tonnes. An Indian on average consumes 20kg a year or about 13 spoons of sugar a day. That’s about five more than the medically recommended daily intake.

To put in perspective, Indians have better access to unhealthy sugar than fresh vegetables. Indians on average eat two portions or 250g of vegetables a day, about half the recommended quantity. The Indian government gives 1kg of sugar free to nearly 2.5 crore poorest households through the public distribution system. But the sugar industry will be quick to point out that India’s sugar consumption is much lower than the global average of 23kg, and 56kg for developed countries such as US.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there are an estimated 77 million Indians suffering from diabetes and nearly 25 million are prediabetics (at a higher risk of developing diabetes in near future). The country accounts for about 17% of the world’s diabetics.

Yet, the government and the sugar industry want Indians to consume more.

Why are Indian governments addicted to sugar?

It’s a combination of electoral concerns and the inability to reform an inefficient system.

Let’s first understand the importance of the sugarcane crop. Nearly five crore farmers depend on sugarcane and the sugar industry. A 2020 Niti Aayog Task Force Report on the sugar industry says that its annual turnover is about Rs 1 lakh crore, generating a revenue of Rs 12,000 crore for the government exchequer. “However, the sector has been facing serious issues related to profitability as well as liquidity in the last few years due to depressed sugar prices inadequately covering cane prices and mismatch between sugarcane prices and sugar prices,” it notes.

In other words, it takes more money to produce sugar in India compared to global prices. That makes Indian sugar not very competitive. In the last year or so, things have been better because international prices have gone up due to lower production in Brazil. Indian sugar is inefficient and expensive because the government provides farmers with dollops of financial incentives to grow more.

Unlike rice and wheat sugarcane does not have a minimum support price (MSP), the rate at which the government buys grains primarily from the farmers in Punjab and Haryana. Instead, the government fixes what is called the fair and remunerative price (FRP) that the sugar mills must pay farmers. The mills are mandated to buy at that price from all the local farmers in their catchment. The FRP for the 2022-23 sugar season was Rs 305 per quintal of cane.

“The returns from sugarcane cultivation are generally 60%–70% higher than most other crops. Remunerative and assured prices along with improvement in yield and recovery continue to attract farmers to growing sugarcane despite ample supply and lower prices of sugar in the market. It would not be an exaggeration to say that India has structurally become a sugar-surplus nation,” says the Niti Aayog report.

Since 2012, the FRP has increased 80%. Farmers of no other crop in India get the privilege of such steady and assured increment. Since 2009–10, the FRP has increased by about 111% (in 10 years). The net return on cultivating sugarcane is 200%–250% higher than cotton and wheat.

That’s not all. Several state governments sweeten the deal for farmers by offering bonus on top of the FRP fixed by the central government. That becomes the price at which mills must buy from farmers. For instance, in 2022-23, the Haryana government set the SAP at Rs 372, significantly more than the FRP. Farmer bodies demanded Rs 400. Punjab, UP, the largest sugar producer, and Uttarakhand followed a similar course.

With the ability to influence the electoral outcome in nearly 60 Lok Sabha seats across the country, politicians go out of their way to keep them happy.

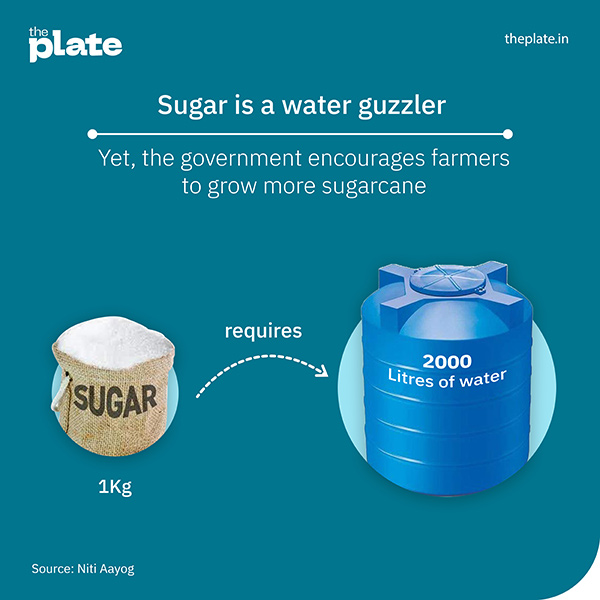

Sugarcane is not just a water guzzler requiring in excess of 2,000 litres of water per kilo of sugar compared to 300-500 litres for millets such as ragi or foxtail, but also a lazy farmer’s crop.

Like the 1990s Hero Honda tagline “fill it, shut it, forget it” that advertised the four-stroke motorbike’s fuel efficiency, sugarcane can be described as a “sow it, fill it (the land with water), forget it” crop. Sugarcane is a sturdy 10 to15-month crop that requires little attention, inputs, labour or maintenance unlike say vegetable crops.

In Maharashtra for instance, sugarcane occupies less than 6% of the total cultivated land but drinks up nearly 70% of its irrigated water.

Considering all the financial incentives, cost of producing a kilo of sugar in India goes up to Rs 35 compared to Rs 18-20 internationally. Indian sugar is currently in demand because global sugar prices are now high due to a drop in production in Brazil. But in general, Indian sugar is highly uncompetitive in the global markets. In fact, in 2019, Australia, Brazil, and Guatemala complained against India at the WTO arguing that it was dumping highly subsidised sugar in international markets. They argued that India’s sugar subsidies far exceeded WTO norms.

Isn’t it good that India is making ethanol from sugarcane that can be used as fuel?

Since India’s sugar isn’t globally competitive, and the financial incentives for farmers to grow more difficult to undo for political reasons, the question to ask is if India is trying to justify its over-production of sugar by diverting some of it to make ethanol. In 2022, India used up 3.6 million tonnes or about 10% of its sugar to make ethanol. India currently adds 10% ethanol to petrol and plans to take it up to 20% by 2030. This policy, the government claims will help India reduce its petroleum import bill proportionately.

Now, producing ethanol as a fuel from sugarcane is neither all that sustainable nor economical as it’s touted to be. A litre of ethanol at current prices costs nearly Rs 67. For ethanol blending to make commercial sense, fuel prices need to remain high. Also, promotion of ethanol doesn’t tally with the big government push for electric vehicles. As a 2022 report from the Observer Research Foundation pointed out: The gains in tailpipe emissions from ethanol blending are not only too small but also redundant given India’s goal for electrifying surface transport.

It’s high time India went for a sugar rehab.

What was the Green Revolution, and does India need another?

Posted on April 5th, 2023

Any conversation about food and agriculture or even India’s history since Independence would be incomplete without looking at the Green Revolution. The Green Revolution led to a massive jump in food production, making a poor nation self-sufficient in foodgrains. For that reason alone the Green Revolution could be put right at the top of events that shaped modern India.

For a historical perspective, and an understanding of the conditions before the Green Revolution, and its gains, TR Vivek and Aarthi Ramachandran spoke to Harish Damodaran, National Rural Affairs and Agriculture Editor at The Indian Express and Senior Visiting Fellow, Center for Policy Research, New Delhi.

Q1

What is the Green Revolution? Tell us about the times, the India of the 1960s, when the seeds of this revolution were sown.

In 1965-66 and 1966-67 India faced back-to-back droughts. Our food grain production fell to something like 72-74 million tonnes. Earlier it was about 80-82 million tonnes, and in 1966-67 alone, India imported about 10 million tonnes of foodgrains. It was basically a ship-to-mouth existence.

The Green Revolution was centered around two crops, wheat and rice. It basically involved changing the plant architecture [of these crops]. What scientists did was to breed, what they called, a ‘new plant type’: semi-dwarf plants [that would yield more grain.] This was done by way of an international collaboration.

Until about 1966-67, our wheat production was hardly 10-12 million tonnes. When Green Revolution was launched, the production touched 16.5 million tonnes, and by 1969-72 it had crossed 20 million tonnes. It was a remarkable international collaboration between the Rockefeller Foundation, Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), Dr Orville Vogel, Dr Norman Borlaug and Dr MS Swaminathan . The same strategy was also followed for rice, and the initiative came from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in The Philippines.

Q2

Can you give us a sense of what was there before and how the Green Revolution changed that scenario completely?

The scientists and planners first introduced the Green Revolution varieties in Punjab and Haryana. These two states had plenty of water, good land, and progressive farmers. Our ship-to-mouth status meant time was running out. So instead of introducing them in say, Madhya Pradesh or Eastern UP, they chose Punjab and Haryana for quick results.

The second thing which the government did was the setting up of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and announcing a minimum support price (MSP). The other very important thing which had happened in the 1950s itself was we had created agricultural universities, like the Punjab Agricultural University. So these were collaborations; US scientists came and they helped set up these universities. Also during this time, fertiliser plants came up. So I think we invested in the entire ecosystem.

If you look at our foodgrain production in the 1960s, it was about 80 to 82 million tonnes. Today we are at 300 million tonnes. These are the remarkable achievements.

COVID 19 was an unprecedented pandemic where nobody died of starvation. That came only because of the Green Revolution. Of course, vaccines were celebrated, but for me, the real success story was the free rice and wheat distributed to 800 million people. So I think the Green Revolution’s real moment came in 2020 and 2021.

Q3

The Green Revolution has obviously done fantastic things. But there were violent incidents in some states between big farmers who had become richer and people working the land who felt left out. Was the social aspect not adequately examined?

I’m not sure how much of this was a result of the Green Revolution. There’s no doubt that higher yields and increased farm income produced a middle peasantry. I wouldn’t say that it produced very rich peasants, but basically it produced a new middle class, a new rural middle class.

Also, overtime, it spread to the other states. So I think this is a little exaggerated to say it only benefitted the rich farmers. I don’t think there were any social conflicts because of the Green Revolution. I think the Green Revolution had problems more with, maybe, the environmental effects.

Q4

Today it is very fashionable in some sections to portray the Green Revolution as ‘evil’ because of the supposed environmental damage it has caused. Is that a fair view?

The strategy in Green Revolution 1.0 was about making crops more responsive to fertiliser and water application. Green Revolution 2.0 may actually be about more efficient use of resources. How do you produce more on the same land with less fertiliser and less water?

We shouldn’t rubbish Green Revolution 1.0. We need to continue to trust science. I think that is the most important thing. I’m a little afraid of this entire discourse rubbishing the Green Revolution—that it ignored nutrition, only increased food production. At the end of the day we have improved our life expectancy. Mortality has come down. We need a more constructive debate on how to improve yields using less. We need constructive not cynical engagement.

Q5

Do you see a place for millets within Green Revolution 2.0? If millets were given the same kind of support that rice and wheat were, can they really become a serious alternative?

Definitely, why not? But we need to pick winners. I think there’s more potential in bajra, ragi and jowar than in other small millets. We should focus on states that would be ready to do this. For example, Orissa has a millet mission and they are focusing more on ragi. So you can have Karnataka and Odisha for ragi, you can have Haryana and Rajasthan focussing on bajra, and Maharashtra, jowar. Millet farmers should be given minimum support price and procurement support.

It would be viable to distribute millet-based food through the mid-day meal scheme rather than the public distribution system. We have 25 crore school children and 15 lakh schools. That is a huge market. I think the mid-day meals programme has a lot of scope and can address what Green Revolution 1.0 did not do—the question of nutrition.

Q6

Is there something about the current political climate or competitive political culture that hinders Green Revolution 2.0?

I don’t think there’s any competition in politics today. The ruling party today is as strong as the Congress was in the 1960s and 70s. I don’t think there are any political impediments, but definitely we need good agriculture ministers. We really need a minister for farmers, who would first think of farmers. Ultimately the producer is the consumer’s best friend. We should be able to strengthen the producer.

How a Nashik company owned and run by small grape farmers turned into a Rs 1000cr export giant

Posted on April 5th, 2023

A little past 3 pm, during the day’s second shift, just when the chatter of a thousand workers—mostly women, sanitised, and clad in bouffant caps and bottle green factory jackets—fully folds into the hum of machines to produce peak agro-industrial harmony at Sahyadri Farms’ massive grape packing unit, everything comes to an abrupt halt.

A visibly distressed male supervisor in a white lab coat using the PA system calls attention. There’s a lot of barking out of instructions, and some pleading involved. A worker packing freshly harvested grapes has accidentally dropped her meal coupon into one of the 500g punnets (a bread-shaped, transparent plastic box) on its way to the UK supermarket chain, Tesco.

Given Europe’s extremely high income levels and the demand for food imports because it can’t grow enough of what it needs all year round, it is the most coveted market for exporters all over the world. On the flipside, it is also the most finicky and exacting when it comes to food standards. Indian exporters feel EU strictures on the curvature of bananas, pesticide and sugar levels in other fruits and vegetables are often discriminatory.

While the error has been spotted before the box left the conveyor belt, the supervisor reminds every one of the real cost of such small acts of inattention. An entire shipment of grapes with dozens of containers (each carrying 16-20 tonnes), worth millions of dollars could get rejected, putting at risk thousands of farmers’ hard work of a whole year.

Yes, the stakes are that high at Sahyadri.

Strength in numbers

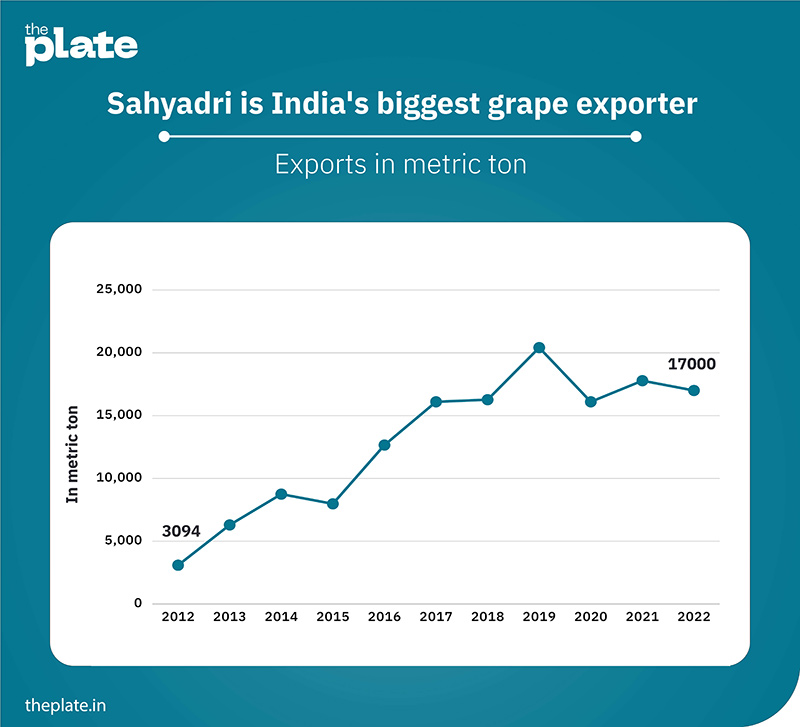

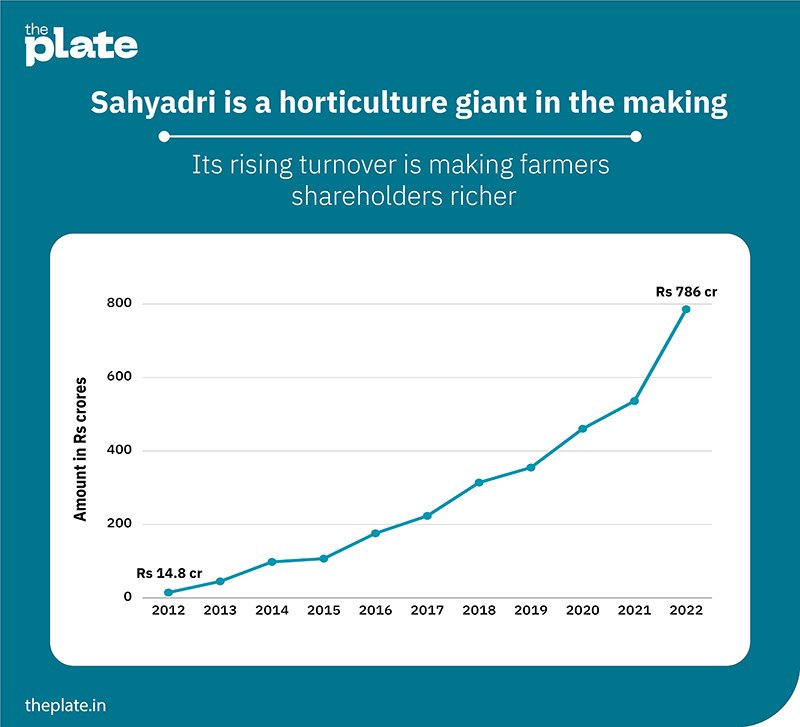

After all, Sahyadri Farms, in just 12 years of its founding, is now the country’s largest exporter of grapes. Almost 17% of the grapes that leave India’s shores are sold by Sahyadri—far more than pedigreed players such as Mahindra Agri. In 2023, its revenue crossed Rs 1000 crore. It is the largest producer and processor of tomatoes, making almost 50% of all Kissan tomato ketchup, a brand owned by global food giant Unilever.

Sahyadri Farms is a unique company that is owned, managed and run by a large collective of farmers. It belongs to a class of companies called farmer producer companies (FPC) which are a hybrid between a cooperative, such as Amul, and a private limited enterprise.

An FPC can be formed when 10 or more farmers growing the same produce, grapes in Sahyadri’s case, or say milk or turmeric, band together.

“Indian farmers have two options: collectivise or quit,” says Vilas Vishnu Shinde, the 49-year-old founder and chairman of Sahyadri Farms in a soft tone, vocal cords leathered by shouting slogans demanding a fairer deal for farmers in his youth.

Don’t mistake Shinde’s call for Soviet-style collective farming. That involved the government taking ownership of all farmland and reducing farmers to employees, who worked without a profit motive, to produce cheap and plentiful food for people in the cities.

Clad in a white linen shirt and jeans, the sharp-shaven, mustachioed, short and stocky Shinde wants Indian farmers to be rich, as rich as the IT professionals in the cities they feed.

Losses unlimited

Being a farmer in India is possibly the cruelest hand destiny can deal. Nearly 75% of Indian farmers own less than one hectare of land. That’s barely the size of a cricket field. The average monthly income of an Indian farming household—a family, not an individual farmer, mind you—according to the latest government data is Rs 10,218. That roughly translates to Rs 340 a day, at par with unskilled, daily wage that labourers in many states get under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), a scheme whose existence is testimony to India’s failure at rural uplift.

India’s agro-economy seems designed to fail Indian farmers. Small farmers buy all their inputs (pesticides, seeds, fertilisers and equipment) at retail rates and sell their output at wholesale prices. They have absolutely no bargaining power when buying or selling. Even a super-duper, bumper harvest of 10,000 kg of grapes from an acre of land, after year-round toil, at a farmgate price of Rs 30/kg means an annual income of Rs 300,000. And grapes generally offer better income than staples such as rice, wheat, onions and tomato, where according to even the most generous estimates, the farmer gets a mere Rs 30 for Rs 100 paid by the urban consumer. Greater the number of handlers from the moment a farmer loads his harvest on the truck (sorting and grading of the produce at a wholesaler’s yard; stuffing them into jute gunnies; or packing them in to smaller plastic bags with a brand sticker) to when it reaches your plate, wider the gap between the price you pay and what the farmer earns.

In theory, when individual farmers organise themselves as an FPC or a cooperative, their hand gets stronger. A collective of farmers with 500 tonnes of grapes compared to just 10 tonnes can drive a harder bargain with Ambani, Adani or even global buyers. While FPCs are a collective, they can be run as any for-profit private sector company. Unlike cooperatives, FPCs are free of government control and meddling.

“Indian farmers have to come together to benefit from the economies of scale; think of farming as a business; think of themselves as entrepreneur-managers of their farms; and compete in the global marketplace and win,” Shinde says.

Fighting the ten-headed monster

The nearly 800 grape farmers, owning small pockets of land ranging from two to five five acres in Maharashtra’s Nashik region, who joined hands a decade ago to form the Sahyadri Farmers Producer Company, are considerably prosperous. Many have farm income now in excess of Rs 1 crore, and the current value of their shares in the company could even make some millionaires.

Sahyadri today is not just India’s largest FPC, widely seen as the model to emulate for farmers across the country, but is a sort of holding company for 48 different FPCs with 18,000 farmers in its fold. When it comes to grapes, Sahyadri now has zonal FPCs bringing together grape farmers in a particular area of districts within Nashik, Sangli and Satara, or some created specific to a crop in a region – banana FPCs in neighbouring Jalgaon or citrus and cotton FPCs in Vidarbha.

The formation of about 10,000 such FPCs is a cornerstone of the government’s plans to increase farm income.

“To be a farmer in India is like fighting a ten-headed Ravana. You think you’ve solved one problem and nine crop up. We are up against countless invisible and unpredictable factors. First, there is nature. A whole year’s hard work can be washed away by unseasonal rains at harvest time; water shortage kills us. The global prices may crash or the government might change its policy overnight. There is simply no way a small farmer can win,” says Shinde.

Collectivisation isn’t a new idea in Maharashtra. The co-operative movement in sugarcane has a rich legacy in the state. In the past decades, it had bettered the lives of millions of cane farmers especially in the Marathwada region. But overtime, with government interference built into the co-operative model, the institutions were hijacked by politicians who in turn became sugar barons. “Sugar Cooperatives were given land at throwaway prices by the state to build schools and engineering colleges to benefit the children of farmers. Now, the system has become so perverted that the seats at these colleges are sold to rich students from big cities. An ordinary farmer now can’t even enter these swanky campuses,” says Radheshyam Jadhav, a Pune-based journalist and Deputy Editor at Businessline newspaper, who has tracked Maharashtra’s agro political economy for nearly three decades.

That’s the reason why Shinde says he is determined to keep political interest of any colour or persuasion completely out of Sahyadri. But, is it possible to keep politicians at bay for long?

“If you don’t seek favours from politicians, you can stand up to them and say ‘no’ to their demands. Also, we deliberately avoid dealing in crops like rice, wheat or onion that have heavy government control. Fighting the government is a waste of time and energy. In grapes for instance, the government is actually promoting exports,” he explains.

The idea of “winning” is pervasive in Sahyadri’s grape ecosystem in particular and among Nashik’s farmers in general. Sahyadri and Shinde are obsessed with winning.

But their seeds of success lay in failure.

Two men who looked west

Every vine in the world today that produces luscious grapes is a result of careful grafting. A variety called Arra is the most popular among Sahyadri farmers. But it can’t be planted directly on the fields. A small section of Arra stem (called scion, because it’s the fruit of this variety that farmers want) is wedged and taped on to another grape variant that has already laid roots and grown about half a foot tall. That’s called the root stock. The root stock is usually closer to the wild varieties. They don’t bear fruits but are tenacious. They can withstand high temperatures, droughts and even saline soil. The most coveted root stock in India is a non-fruiting variety called the Bangalore Dogridge. A vine resulting from such a marriage consummated in the nurseries can bear fruit for more than a decade.

Just as the grapevine need grafting, Sahyadri’s success needed two men of vastly different backgrounds. One was a farmer, the other a slick salesman with the gift of the gab and the ability to make a pitch tailored to fit any whim.

But they were of the same mental stock that kept this question constantly afloat in their heads: why are Indian farmers poor?

Azhar Tambuwala is a Pune-boy. At 17, his father met with a serious accident that prevented him from going back to work. With no income to pay fees, Azhar dropped out of college and took up odd-jobs, with little more than the ability to speak English fluently.

In the early 1990s, while dabbling in a variety of businesses, he wangled an order from UK to export a container of grapes. There was a small glitch: Tambuwala didn’t know where and how grapes grew, or did he have a penny in his pocket to buy them off someone who did. “I took a friend’s scooter, borrowed some money, went to Nashik and talked farmers into selling me grapes that could fill a container with the promise of better prices,” says Tambuwala, a tall, thin, bearded man in rimless glasses who is a director at Sahyadri, heading exports and marketing. Beginner’s luck, and India’s gingerly steps towards global trade, birthed a full-fledged business in subsequent years. Servicing small export orders helped Tambuwala save enough money to buy a ticket to London and meet his clients in person.

His single-minded quest in those days was: how do I connect rural India to urban markets, and thence to the world?

A few years later, in the late 1990s, when the business grew bigger, Tambuwala started taking with him an entourage of his farmer-suppliers from Nashik to Europe. These trips had a twin purpose. One, the farmers could hear directly from importers about the kind of produce and quality standards the international market expected. Otherwise, many farmers couldn’t quite fathom why Tambuwala insisted on stringent parameters for how export quality table grapes must look and taste. Rejection of batches that seemed perfectly fine to farmers could erode trust between them and Tambuwala.

Also, they could see for themselves in supermarket aisles the grapes from Chile and South Africa they were competing against.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, during field visits to farms in The Netherlands, they could see their fellow farmers get ten times the yield using modern methods and technology that seemed nothing short of magic. During the time he spent dealing with Nashik’s farmers, Tambuwala found they were extremely ambitious and always on the lookout for new ideas. If they came to know a farmer 100 km away was doing something better, they’d do their best to learn and implement it. “I wanted to break the frog-in-the-well mindset, show them the work ethic and dynamism of farmers in the West and make them realise that there was a global market waiting to be tapped. It made our farmers think, if the Dutch could do it, we could, bloody well, too!” says Tambuwala.

In 2004, on one such visit, Vilas Shinde was one of the farmers.

Mountains of debt

Vilas Shinde was born into a farming family in Adgaon, a village 15 km to the northeast of Nashik. The farm operation his joint family of six uncles ran, with about ten acres of land put together, had never turned in a profit for as long as he could remember. Shinde was a bright student. An M.Tech degree in agriculture from Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, a top agri university in Maharashtra, and the scientific techniques he learned there, failed to fix his family’s fortunes.

The immediate years of youthful agrarian idealism and a burning desire to be debt-free meant dabbling in dairy farming, growing exotic vegetables such as baby corn and broccoli, medicinal herbs, and even a resort to quackery—joining a movement championed by self-styled Gandhian Anna Hazare whose chief methods involved a return to medieval agricultural practices, and ridding rural India of the scourge of alcoholism by flogging drinkers in public.

“It’s a common refrain that farming is a gamble in India. I’ve personally experienced it is true. Only, this game of dice never ends. You keep trying your luck, again and again, crop after crop, season after season, until you accumulate so much loss that there isn’t any more room left to fall,” says Shinde. The net result of his decade-long diversions, up to the early 2000s, was debt that had ballooned from Rs 50,000 to Rs 75 lakh.

Some money was raised pawning his wife’s gold jewellery and selling small parcels of land, but not nearly enough to tackle the mountain of debt. Utterly broken, Shinde says he locked himself up inside the house for nearly five days. When family members, in the guise of getting him to run errands, forced him out to get some fresh air, he bumped into an old friend who asked Shinde if he could help load shipping containers with grapes meant for exports.

Farming is a gamble in India. Only, this game of dice never ends. You keep trying your luck, again and again, until there isn’t any more room left to fall.

Vilas Shinde

Chairman, Sahyadri Farms

Each container when full would earn him Rs 15,000. Quick mental math told him that growing grapes for exports could be good money if merely packing them into boxes provided such handsome rewards. But he had no chance of any meaningful income, forget wiping away debt, with the two acres he owned.

In 2004, he teamed up with ten other grape farmer friends who owned about as much land. This time he was betting on exporting grapes to Europe, the toughest of all markets to crack. When pooled together, their output might become sizable enough to attract an export deal. The punt paid off. A Dutch importer agreed to buy four containers of grapes from Shinde and friends. The export market fetched double, sometimes going up to four times the price grape farmers could get selling locally.

It was the new dawn; spring had come early. Shinde could see the sunlit uplands.

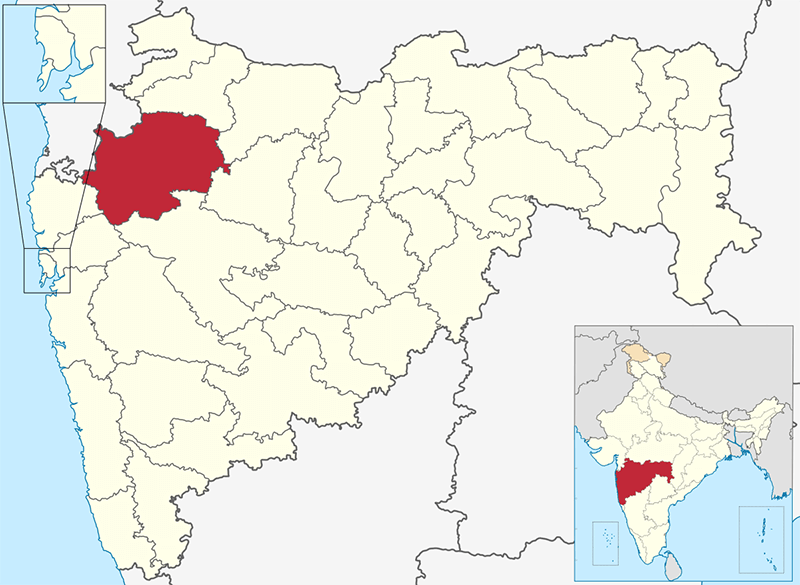

The valley of plenty

The current political boundaries of the Nashik district on the map of Maharashtra make it look like a pheta, the state’s traditional headgear or pagri tilted about 30 degrees to the left. The district’s geography makes it a microcosm of Maharashtra minus the beaches. It has regions ranging from the arid and dry, to mountains that receive incessant rainfall during monsoon, to extremely fertile lands with weather not too cold or dry throughout the year where it’s possible to grow pretty much any crop.

The Western Ghats or the Sahyadri range that stretches across 1600 km of India’s western coast right up to the peninsular tip at Kanyakumari in the deepest south, has its northern extremity 100 km to the north of Nashik district, in Gujarat.

In Nashik district’s Trimbakeshwar range of Western Ghats originates Godavari, the mightiest of India’s peninsular rivers that forms the country’s third largest river basin.

Just as the prodigious precipitation in Kodagu hills in the same Western Ghats in southwest Karnataka fills up a third of Kaveri’s basin, Sahyadri’s northern reaches flood Godavari sustaining three large, thirsty states of Maharashtra, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh and nearly 200 million people.

Godavari translates from Sanskrit as the giver of prosperity. The river is unlikely to keep the children at her headwaters poor. Nashik district’s per capita income of Rs 3.47 lakh, while marginally lower than Maharashtra’s Rs 3.77 lakh, is significantly higher than the national average of Rs 1.97 lakh, and most of it generated from agriculture.

A traditionally strong network of irrigation canals from the dams on Godavari and its tributaries, and farm friendly weather conditions, make the region an agri powerhouse. Nashik remains a veritable vegetable garden of the country growing onions, tomatoes, a host of beans, melons and of course grapes in abundance. Maharashtra produces almost 70% of India’s grapes with Nashik’s two lakh acres alone contributing a whopping 2 million tonnes of the national output of 3.5 million tonnes.

Grapes of love

A vineyard, when ready to harvest, beginning mid-December to March, offers possibly the most spectacular of sights in agriculture.

By late January, the undulating landscape of Nashik when viewed from a vantage is hardly a riot of colours. The tomatoes have been harvested. The fields cleared of plants bare the deep brown soil. Onions sown a couple of weeks ago have green shoots five inches high. In any case, an onion field looks drab. At the peak of peninsular India’s dry season, everything, even the shrubs are a golden straw. Vast tracts of vineyards with their thick canopy, and winter wheat whose silky, shampooed hair-like strands that will turn from green to blonde in a month, offer the only green relief in a sea of brown monochrome.

When you enter a vineyard, head bent and the body a bit crouched, everything feels a few degrees cooler. The grape leaves are broad enough to hold a standard south Indian restaurant-style set of two-idlis-and-generous-chutney. Sunlight filtering through a thick layer of the craggy-outlined grape leaves creates playful shadows.

It is the perfect setting for the most erotic of Biblical poems called the ‘Song of Songs’, an epithet signifying the greatest importance. It can be read as King Solomon’s expression of love for a beloved wife that is intense, untainted by selfishness and sin, or as an allegory for Christ’s love for his followers and vice versa.

It goes:

Let us get up early to the vineyards;

let us see if the vine flourish,

whether the tender grape appear,

and the pomegranates bud forth: there I will I give thee my love

The Biblical song inspired one of India’s best romantic movies. The legendary Malayalam director Padmarajan made a film in 1986 called ‘Namukku Parkkan Munthirithoppukal’ (A vineyard for us to dwell in) starring Mohanlal, a Syrian Christian grape farmer, appropriately named Solomon who wins the hand of a woman named Sofia (not Sheeba, lest it gave the game away entirely!). It also features the most romantic of all vineyard songs ever filmed in India. That is of course this writer’s opinion, but we digress.

Today, as more Nashik grape farmers have tasted the fruits of success in the export market, the fields in the run up to harvest wear an odd look. The sun-facing periphery of vineyards are covered by a string of old sarees and thin bedsheets. The grape bunches are wrapped up in old newspapers.

Growing table grapes for exports, while more profitable, is quite demanding compared to wine grapes. Being on the right side of pesticide residue limits aside, the berries must look beautiful. They can’t be too big or small. The emphasis on the uniformity and consistency of size and shape and colour of each harvested bunch is such that you wonder if western consumers want produce shaped and nourished by nature, or fruits injection moulded in a factory. Excessive sunlight creates two problems. It ripens the grapes in a bunch inconsistently, and hastens the build-up of sugar. The level of sweetness Indians expect in grapes just wouldn’t cut it in Europe. The Brix scale is a measure of dissolved sugar content in any solution. It is used to measure the sweetness of fruits such as grapes. The Brix content for grapes to Europe must range from 16 to 20 degrees, whereas the Indian palate prefers sugar content 24 degrees or higher.

A change of fortunes

In the spring of 2004, when Shinde and friends shipped the first of their export order of four containers of grapes to The Netherlands, Shinde’s hopes of a bright future knew no bounds. Despite some initial glitches, the business thrived. By 2010, the group had expanded to 25 friends, and with the help of Tambuwala’s sales acumen, they were exporting 160 containers of grapes.

A major crisis struck just then. The European Union put in place stringent restrictions on the residue of a plant growth hormone controller called Lihocine (ironically, a brand sold by German chemical giant BASF). The grapes Shinde sent to the continent were rejected outright. Markets crashed all over. A box fetching 10 euros had to be offloaded at 10 cents.

“The use of Lihocin was an accepted practice across the world. Nobody, the importers or the Indian government informed us about the new residue levels of Lihocin because we were too insignificant. Forget my personal debt, I had now pulled in all my friends who believed in me, into an even bigger hole. There couldn’t be a crop for next season’s exports. There would be no money to even pay farm labour. The banks told us the only option we had was to sell our land and pay all the loans. We didn’t have the courage to tell our families what had happened. I was back to square one,” recalls Shinde.

Call it irrational exuberance, or the last throw of dice. Vilas Shinde sold all his land from the profits he had made six years past to recompense everyone’s loss.

Such leadership in adversity proved to be the perfect sales pitch in attracting more grape farmers.

“I can’t forget the sacrifices Vilas anna made to get people like me prosperous,” says Govind Uphade, a 38-year-old grape farmer in the Dindori taluk of Nashik district. But there is no time to get too sentimental. Harvesting scissors in hand, Uphade, a slender man wearing a white shirt stained by grape sap, sleeves buttoned down, and black polyester trousers, mentions almost matter-of-factly that his annual family income is Rs 1.25 crore from a holding of 40 acres compared to the two acres he owned before joining hands with Shinde in 2010.

Extensive use of technology helps to maintain the quality that would fetch farmers the best price. For instance, with digitalised farms, every box of grapes can be traced right down to the vineyard. Sensors and IoT devices at the vineyards capture key data that is supplied to the farmers in the form of a simple dashboard on Sahyadri’s mobile app. “Our team of agronomists too can monitor if individual farmers are following the right processes. We can see real time soil, moisture content, whether the plants need watering, analyse changes in leaf colour to predict the onset of a disease or pest attack and recommend preventive care,” says Sacheen Walunj, CEO, Sahyadri FPC.

“We had seen the benefits of coming together and competing in the global marketplace. Relying on the government for help is futile, farmers must look after their own interest. They have to find solutions for their problems by getting together. To export grapes, you need to have a cold chain. Post packaging, they need to be pre-cooled at zero degree Celsius for a shelf life of 60 days. How can an individual farmer with two acres do it,” says Shinde over a special Republic Day breakfast of pav bhaji and jalebis at the Sahyadri canteen.

A fruity Amul?

It would be unfair to speak of Amul, a Rs 61,000 crore farmers’ cooperative and global dairy giant in the same breath as the Rs 1000 crore Sahyadri.

But listening to Shinde, Tambuwala and Sahyadri members on why farmers need to think as entrepreneurs, use professional management approaches, and look at the market as an opportunity rather than a threat, it would appear they are singing from the scoresheet of Varghese Kurien, the founder of Amul and chief architect of India’s White Revolution. In his 2005 autobiography, I Too Had a Dream, he wrote: “Today India is among the most industrialised nations in the world. How did this happen? It happened because we combined our native shrewdness and the money our great industrialists had with professional management. I was convinced that the biggest power in India is the power of its people – the power of millions of farmers and their families. What if we mobilised them, if we combined this farmer power with professional management? What could they not achieve? What could India not become?”

I was convinced that the biggest power in India is the power of its people – the power of millions of farmers and their families. What if we mobilised them, if we combined this farmer power with professional management? What could they not achieve? What could India not become?

Varghese Kurien, the founder of Amul and chief architect of India’s White Revolution In his 2005 autobiography, I Too Had a Dream

Mark Kahn, managing partner at Omnivore, a venture capital firm focussed on investing in the country’s agri sector, too, sees parallels between Amul and Sahyadri.

“Sahyadri’s success is analogous to the White revolution and Amul. Back then, two factors were at play: one, a strong leader like Varghese Kurien comes along and changes everything. The second is institutional. Dairy farmers had an inherent need to co-operate with a perishable product that loses all value in two days. A farmer with two animals can’t afford milk chilling or processing infrastructure. Similarly in Nashik, the impact Vilas Shinde has had as a farmer leader is phenomenal. And if you put together a thousand grape farmers, who are individually profitable, they could afford refrigeration, cold chains and other infrastructure to target the global market,” says Kahn, a tall slender American with thick-rimmed glasses, who is more gung-ho about Indian farming than most Indians.

In 2011, Sahyadri began operations as a full-fledged FPC and by 2016 had the means to set up a 110-acre factory-cum-headquarters where it can process not just 300 tonnes of grapes a day but 1,200 tonnes of tomatoes. While grapes are seasonal, the nonstop, year-round processing of tomatoes keeps the impressive campus with its red brick office buildings, giant white-roofed warehouses and manicured lawns soaked in a smell of ketchupy sourness.

The impact Vilas Shinde has had as a farmer leader is phenomenal. If you put together a thousand grape farmers, who are individually profitable, they could afford the infrastructure to target global markets.

Mark Kahn

Managing Partner, Omnivore

Besides grapes and onions, Nashik is one of India’s biggest tomato producing regions. Among India’s chief vegetables, tomato prices are prone to the wildest price fluctuations. While prices skyrocket between May and September because of extreme summer heat and monsoon disruptions, there is often such a glut of supply in winter and spring that prices crash to almost Rs 2 a kilo at the farmgate. At that price, it doesn’t even make sense to harvest the tomatoes. That is when the images of farmers dumping tomatoes by the tractorloads in protest make headlines.

Tomatoes are in demand all through the year. There’s no reason it should have the billing of ‘the tragic crop’ among farmers. “We can easily solve the problem of seasonal excess through processing of tomatoes. Whenever the price drops below Rs 5/kg we start buying in big quantities from the farmers so that they can at least recover their cost,” says Shinde. Sahyadri is now the biggest contract manufacturer of Kissan ketchups and fruit squashes.

Sahyadri has become the first farmer owned company in India to attract foreign investment. In September 2022, it raised Rs 310 crore from a clutch of European investors. What makes Sahyadri the most successful FPC? “You need a crop specific, integrated value chain approach where the farmer is in control of all things from the farm to the market. And that value chain should be globally competitive,” says Shinde.

With foreign investment comes criticism from some farmers outside of its network that Sahyadri is now run like any other corporate firm. Shinde even has ambitions of listing the company on the stock markets in the next five years. Keeping investors happy might take precedence over the betterment of farmers?

“That’s nonsense,” says Kahn. “They’ve carved out the food processing part of the business and used it to raise money. But it is still owned by the FPC and the farmers. Look, everyone says, oh, an FPC needs investment to attract talent. For that you need money. Sahyadri has done just that. It needs to be celebrated rather than say it compromises the spirit of an FPC.”

What is Indian agriculture? And why you must care about it

Posted on April 3rd, 2023

Indian agriculture is an extremely complex and vital sector of the economy.

But, going by the stories you read in the Indian press, you’d think it’s one long sob story: farmers committing suicides; perennial poverty; and the weather and price fluctuations making the profession so uncertain that it’s a gamble.

Yes, all of it is real, but, not the only reality.

Here’s why you should care and take pride.

Indian food and agriculture a $630 billion dollar sector. It contributes nearly 18% to Indian’s $3.5 trillion economy. That’s almost more than the GDP of Norway or almost twice Pakistan’s entire economy.

Incredible diversity

Indian agriculture feeds 1.4 billion people, guaranteeing national security. It is incredibly large and diverse.

Nearly 40% of India’s entire geographical area, around 140 million hectares or area roughly the size of Peru, is used for agriculture. Only the US has more farmland than India.

India has 15 different agro-climatic zones, each with its own unique set of weather and soil conditions, which determine the types of crops that can be grown in the region.

From the cold and high-altitude western Himalayas where apples and peaches grow, to the hot, humid and flat-as-a-dosa plains of the eastern coast that yield enormous quantities of rice, sugarcane and fruits like banana, this diversity has helped India achieve self-sufficiency in food production and become one of the major food producers in the world.

India has two major agri seasons called Kharif and Rabi. Kharif, the summer season, lasts from April to September. Most of India’s rice grows in this season. Rabi or the winter season, when all of its wheat is produced, lasts from October to March.

Such diversity means the country can produce almost every major agricultural commodity.

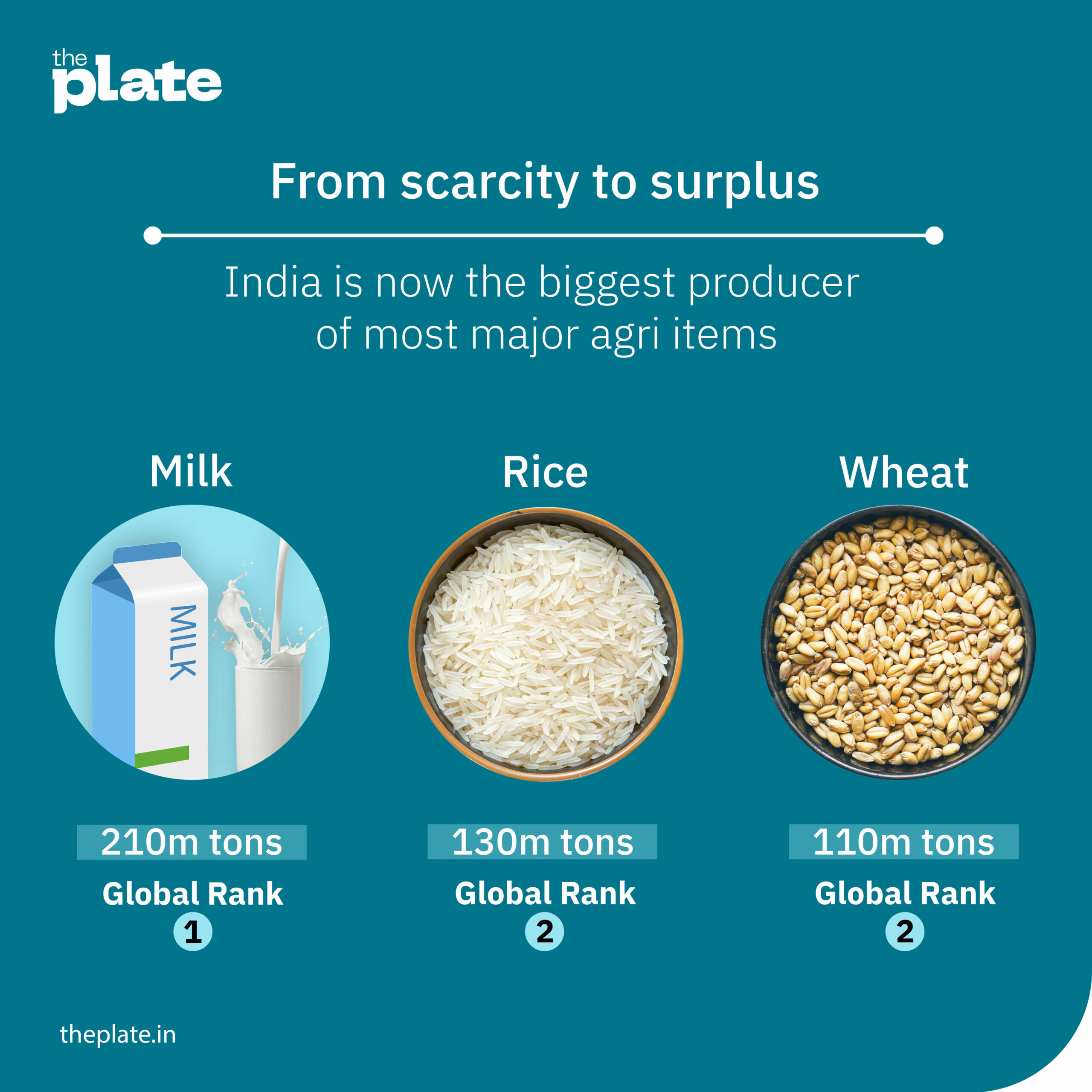

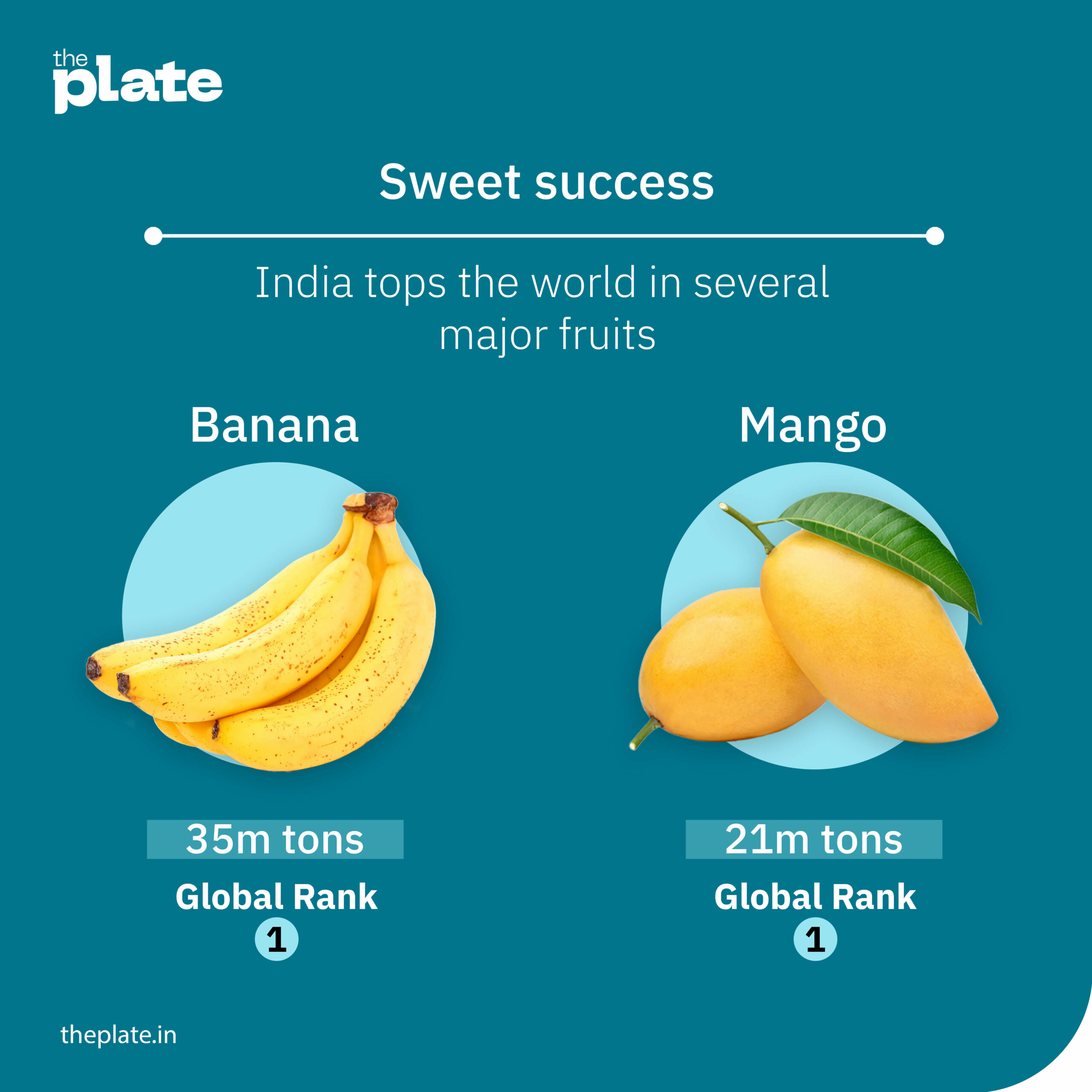

India produces 210 million tonnes, or nearly 25% of the world’s milk making it the biggest in the world. It is the second largest producer of rice, wheat, fruits and vegetables, cotton, and sugarcane.

However, until the 1970s India routinely faced food shortages.

Seeds of modernity

In the 1960s, it had become a ship-to-mouth economy. It relied heavily on substandard and subsidised foodgrains from the US as aid. This was a recurring national humiliation.

In response, India in partnership with international organizations such as the Rockefeller Foundation and International Rice Research Institute, adopted new technology, high yielding varieties of rice and wheat, and increased its irrigation network.

This was called India’s Green Revolution, perhaps Independent India’s most transformative event. Crop yields increased; food shortages came down significantly.

Thanks to Green Revolution, India’s food grain production has increased six times from 50 million tonnes in 1950 to 315 million tonnes in 2022, while the population increased about four-fold from 360 million to 1.4 billion.

From begging for food aid, India is now food surplus. In 2021 India exported agricultural commodities and processed food worth $50 billion.

India provides 92 million tonnes or nearly a third of all the grain it produces at subsidised rates through various welfare schemes to nearly 800 million poor people.

But the good news kind of ends here.

An ‘Evergreen Revolution‘

Despite the improvements, Indian agriculture remains massively inefficient by global standards. It employs nearly half of the country’s population to contribute less than a fifth of the economic output. India produces just four tonnes of rice per hectare compared to China’s average of seven tonnes.

About 87% of Indian farmers have less than two acres of land, roughly the size of a cricket field.

The landholding size in India has been declining over time. As families grow, the land gets fragmented of land into smaller plots.

Smaller farms make it difficult for farmers to adopt modern technologies and practices that require a larger scale of operation.

For example, large-scale mechanization, precision farming techniques like drip irrigation, and other modern inputs and technologies may not be feasible for farmers with small landholdings.

The shrinking of landholding size has also contributed to declining incomes and increasing poverty among farmers in India. With smaller landholdings, farmers may have less land available for cultivation, which can lead to reduced crop yields and lower incomes.

But a second Green Revolution, or what MS Swaminathan, one of its architects calls an ‘Evergreen Revolution’ of can reverse this trend.

Promoting the use of technologies that make farming efficient, produce more with lesser resources, produce healthier and ecologically sustainable food, and giving farmers better access to local and global markets will allow Indian agriculture to not just ensure the country’s food security but also make it enormously prosperous and healthy.

Why India faces a constant onion crisis

Posted on March 30th, 2023

Why is onion so important in India?

Onion is India’s second most favourite (after potato) and the Number One politically sensitive vegetable.

India grows 30 million tonnes of onions. It is the second largest producer behind (you guessed it) China. An Indian household eats 5 kg of onions a month adding up to an annual domestic consumption of 15 million tonnes. Onion accounts for 13% of an average Indian family’s vegetable bill.

From fancy five-star hotels to street food stalls, onions provide body, bulk, a hint of sweetness and pungent pizzazz for Indian curries and chat. For the poor, a fresh onion and a couple of green chillies are often the accompaniment to a meal of rotis or leftover rice soaked overnight in water.

Given the perception that they are poor people’s food, costly onions are a political nightmare.

Why do onion prices fluctuate so insanely in India?

“The simple answer is demand and supply. Onion is a highly climate sensitive crop. When the weather conditions are good, the yields can be phenomenal. Prices crash when there is too much onion in the market. At the same time, winter frost, high spring or summer temperatures, and unseasonal rain can pretty much wipe out a farmer’s whole season worth of crop. That’s when the prices skyrocket,” says Nanasaheb Patil, a director at the Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) that runs India’s largest onion market at Lasalgaon in Maharashtra’s Nashik district, and also a board member at National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED).

But there are several layers to this messy onion story. Let’s try to peel them.

With ample annual production of 30 million tonnes, a large, predictable and growing domestic demand at 15 million tonnes, onion should be a happy story for both farmers and consumers. With production twice the domestic consumption, India should be exporting its surplus and emerge as a global powerhouse.

But the journey of onions from the farm to your plate is pretty much the story of everything that’s rotten about India’s agriculture economy.

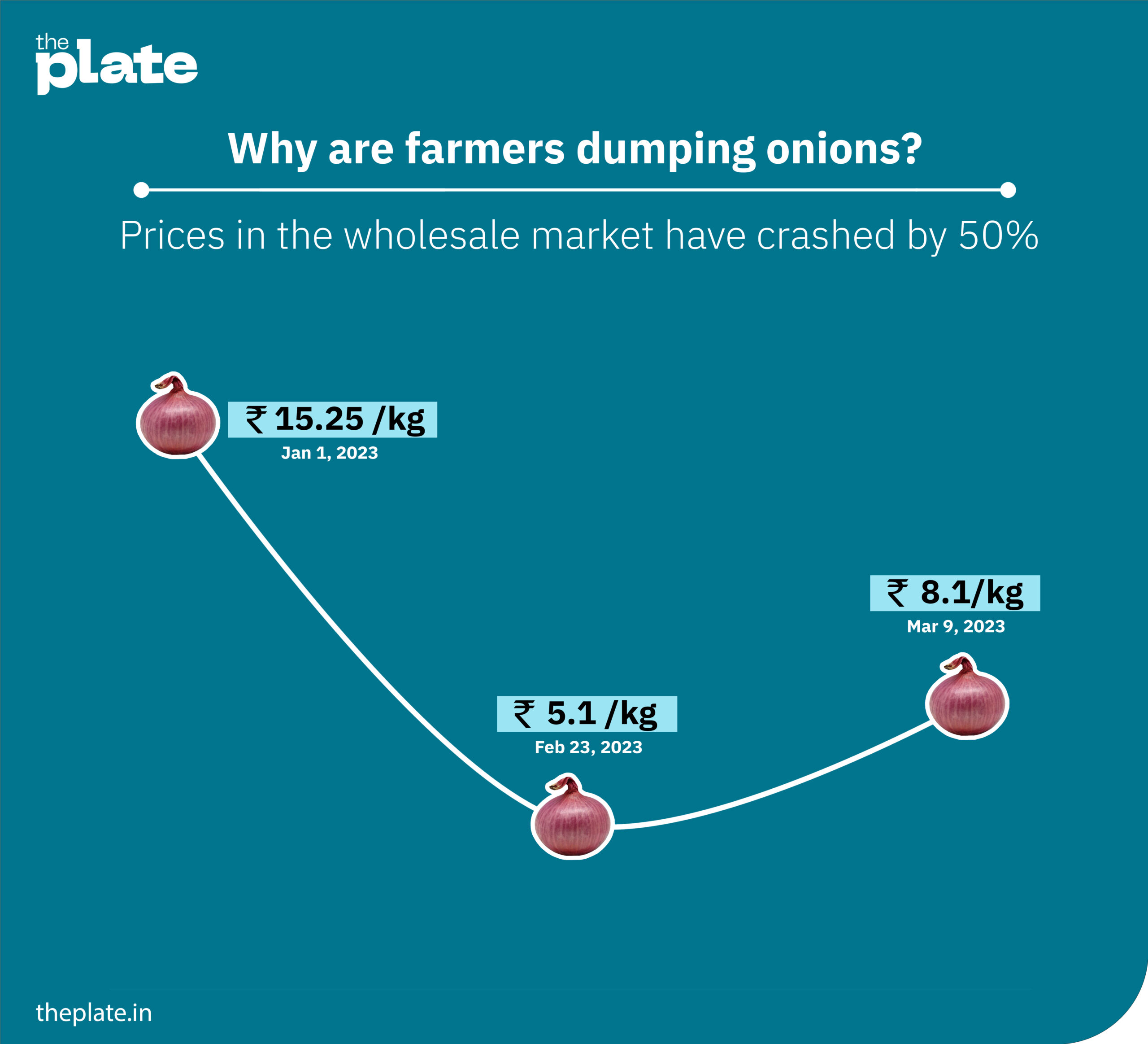

Almost every year, onions make Indians cry in cycles. It’s the farmers now as wholesale prices hover around Rs 5/kg; by November it will be consumers’ turn when retail prices reach Rs 100/kg.

To understand why it happens, we need to understand India’s onion production landscape.

India grows two types of onions: the red which has a shelf life or two weeks and pink, the bigger crop, with a shelf life of nearly six months.

Think of India’s onion production calendar on the map as a Mexican wave. The first crop of fresh onion arrives in August from southern Karnataka. The supply then shifts gradually north: Kolhapur in September, Nashik by October, onions from MP and Rajasthan begin to enter the market by the end of February. The August-to-February cycle brings mostly the more perishable red onions. Immediately after the red season ends, pink onions, called ‘gaonthi’ or ‘gulabi’ start arriving from March to early May. They are India’s mainstay and fetch better prices. The pink onions are stored and released over several months. There is no fresh production until August.

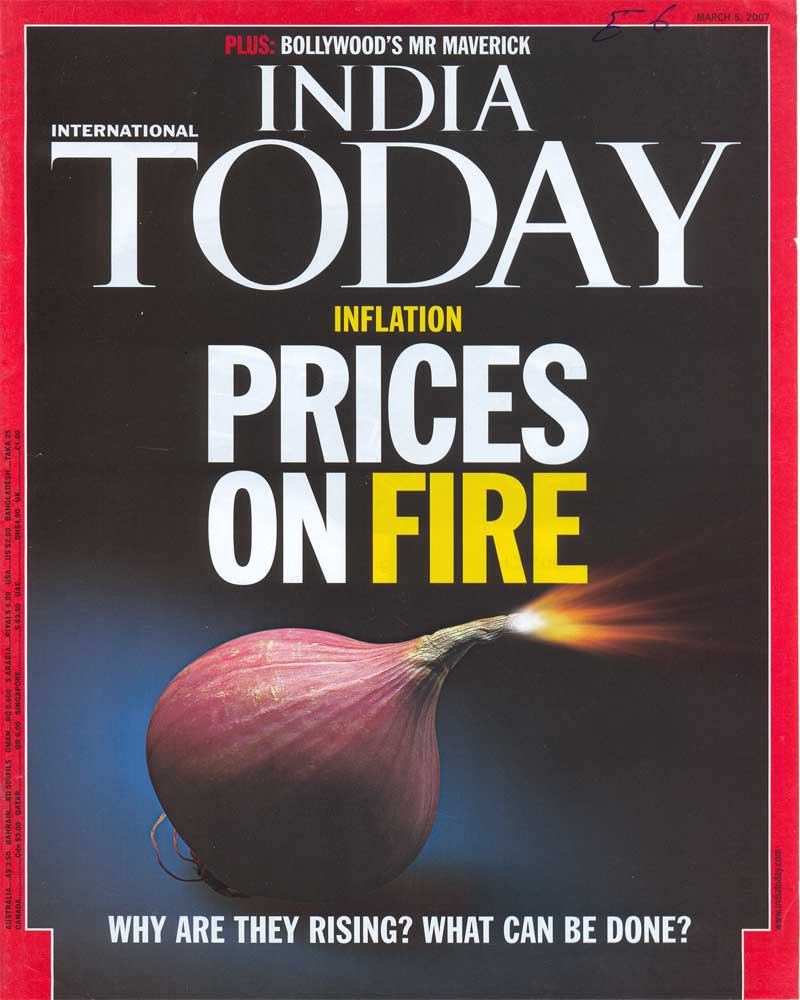

How does high onion prices affect politics?

India’s first taste of a large-scale, countrywide onion crisis was in 1998. In May 1998 India tested nukes at Pokhran. By November, the celebratory mood had vanished. The pride of possessing atom bombs wasn’t enough to overcome the pain of high onion prices.

“A very hot summer damaged the crop in Maharashtra sending onion prices to Rs 75-100/kg. For the first time, the wholesale prices in Lasalgaon touched Rs 40/kg,” recalls Nitin Jain, a trader with such heft in Lasalgaon and elsewhere that many call him the ‘Onion King’. It’s a tag he is keen to underplay. “We hardly do much trading now,” he says with an unconvincing smile.

Lasalgaon, a small town situated 60 km from Nashik, is the epicentre of India’s onion trade. Nearly 2000-3000 tonnes, or about 120 truckloads of onions, are sold by farmers every day here.

Nitin Jain’s father was among those who set up the onion market in Lasalgaon in 1947. On a late January afternoon, sitting in his tiny, musty office, Jain wearing rimless glasses, and black and yellow checked shirt has a fidgety manner.

His two iPhone 14 Pros don’t stop buzzing. On one, he keeps relaying the prevailing price of onions. On the other, he fobs off buyers calling incessantly from Begusarai to Bengaluru, politely telling them he doesn’t have any stock left.

But as soon as the clock strikes 12, Jain puts the phones away, closes his eyes and folds his palms and long, slightly bent-out-of-shape fingers in a prayer pose for a couple of minutes.

“Since that price surge in 1998, governments in Delhi began paying close attention to Lasalgaon and onion prices on a daily basis,” he says.

In 1998 rumours spread in Rajasthan that radiation from the nuclear tests had destroyed the onion crop.

The anger over high onion prices contributed to Delhi’s BJP Chief Minister Sushma Swaraj losing the Assembly election in 1998. The party hasn’t regained power in Delhi since.

Since 1998, banning onion exports when local prices go up, has been a feature of Indian policy. Another favourite tactic of the Central governments is to bring onions under the Essential Commodities Act when prices go up.

It means any trader having a stock of more than 25 tonnes of onions (that’s essentially one single truckload) could be put in jail.

“A few months after the peak of November 1998, the prices crashed again to Rs 1-2/kg in Lasalgaon as the next bumper crop came into the market,” says Jain.

Why have onion prices crashed?

Again, the simple answer is, there more supply currently than demand. There are both local and global factors at play. Most of the major growing regions experienced a bumper crop during the February harvest. And many farmers harvested the crop due in March early fearing damage from the unusually high springtime temperatures.

All of it meant there was too much onion that had nowhere to go. The countries that import onions from India – mostly Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan (not directly, but via UAE), and some in South East Asia stopped buying. Reeling under a severe foreign exchange crisis they cut down imports. Even as exports tanked, India’s failure to connect its farmers to the domestic market made matters worse.

In 2020, the prime minister flagged off a dedicated railway freight service called ‘Kisan Rail’ to carry farm produce across the country faster and cheaper. Farmers could use the service at discounted rates. For the government it served the twin purposes of increasing farmer incomes and ensuring adequate supply of high-demand vegetables like potato, onion and tomato.

Of the 2,400 trains run under the service, more than 1,800 originated from Maharashtra ferrying onions and tomato. “Kisan rail could transport onions from Maharashtra to Bihar and Bengal in 30 hours. But due to severe coal shortages, it has been discontinued for nearly a year. Now the farmers neither have an export market or full access to the domestic market,” says Kshitij Jain who runs Sureshchand Ratanlal Jain and Company, a large onion trade and export firm in Lasalgaon.

Why are onion farmers almost perpetually angry?

It’s because they rarely make a profit. “It costs us about Rs 12-15/kg to grow onions. The cost of labour, transportation, inputs like seeds, fertilisers and pesticides keep rising. There is a lot of weather-related and post-harvest loss. If I harvest 200 quintals from an acre, I only have 135-150 quintals when I sell at the market after all the wastage and moisture loss. To make a small profit, I need to be able to sell for at least Rs 20/kg,” explains Santu Sanap, a three-acre onion farmer in Shivare Phata village on the Nashik-Mumbai highway.

Here’s a shocking fact: farmers at India’s largest onion market, Lasalgaon, end up selling 40% of their produce at a loss. Only a quarter of the onions that enter the market are sold at a profit of 50% or more. Here’s another: for every rupee an urban consumer spends on onions, the farmer gets only 30 paise.

It costs us about Rs 12-15/kg to grow onions. The cost of inputs keeps rising. If I harvest 20,000 kg from an acre, I only have 13,500-15,000 kg when I sell at the market after all the wastage. To make a small profit, I need to be able to sell for at least Rs 20/kg

Santu Sanap

Onion Farmer, Shivare Pheta Village, Nashik

In Lasalgaon market, the sight of journalists and camera crews makes farmers’ anger boil over. “The media comes here only during the month when prices are high. They run headlines like ‘Nashik onion farmers are making the housewife cry’ on TV and make us out to be villains. Where is the media when we are crying for the rest of the year,” bristles Arun Kadam, a farmer from Nilkheda village who has just sold a tractor load of onions much below his production cost.

Nanasaheb Patil had conducted workshops for journalists to help them understand the farmers’ plight. But things haven’t changed much.

Onions are prone to high damage. Nearly 30 percent or 10 million tonnes of onions are wasted on the way from farm to plate. Millions of tons simply rot in godowns, warehouses, and in transit because India hasn’t found a way to efficiently supply onions across the country.

By November, the stock of pink onions dwindles. With bad monsoon or excessive rain (extreme weather is now the new normal) the supply of fresh red onions gets disrupted resulting in a severe crunch smack in the middle of the festive season.

And that’s exactly when the government starts to panic. The first thing the government does to control domestic prices is ban exports. As the second largest global producer of onions, India should be earning billions from exports. It would help farmers earn more. But a knee-jerk export ban every time there is a local price increase, gives India a bad reputation in global markets. Since 2010, India has banned exports four times, and imposed heavy restrictions that pretty much translate into a ban, on eight other occasions.

Tired of pleading India to sell onions in 2019, Bangladesh, the biggest importer, has launched its own onion aatmanirbharta mission. At a time when there is massive global shortage of onions, India has a huge surplus. But buyers in Malaysia or Dubai find India’s export policy fickle. Global markets prefer reliable supply chains.

“Today, productivity is not a problem. We should be a proactive global player. Our embassies should be helping us get better export opportunities. But we are psychologically scared of shortages. There is no proper management, no estimation or forecast of output, no stable export policy,” says Nanasaheb Patil.

The inability to take advantage of global demand grates most farmers in Maharashtra. “To keep people in the cities happy, the government keeps banning and restricting exports when the poor farmer can earn a few rupees more. You will not die if you don’t eat onions for a month when the prices are high.”

The Maharashtra government has agreed to offer onion farmers a temporary bonus of Rs 3.5/kg above the Lasalgaon mandi price.

It is at best a band-aid solution for the ill effects of long-term policy failure.

Let’s start talking seriously about the price of pyaaz that lands up on our plate.