Ranebennur, a nondescript town 300km north of Bengaluru, is the most important hub of hybrid vegetable seed production in India.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

Ranebennur, a nondescript town 300km north of Bengaluru, is the most important hub of hybrid vegetable seed production in India.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

The right socio-economic conditions, availability of trainable talent, clement weather all year-round and a pioneering entrepreneur’s vision to harness it all setting up a sunrise-sector business turns a dozy place into a prosperous hub of startups. This isn’t yet another paean to Bengaluru’s status as the ‘Silicon Valley’ of India. It is the story of a place smack in the geographical centre of Karnataka, 300km to the northwest of Bengaluru called Ranebennur that’s the epicentre of India’s hybrid vegetable seed production.

Since seeds are the most critical and fundamental unit of input in agriculture, it would not be an exaggeration to call such a place ‘startup town’.

Seeds of success

Ranebennur is where India’s largescale, commercial production of hybrid vegetable seeds began in the late 1970s. Today, most major national and multinational agriculture companies from Syngenta to Pioneer to Namdhari have operations in the region. The farmers in this small region produce roughly Rs 500-crore worth of hybrid seeds of vegetables such as tomatoes, chillies, brinjal, okra and assorted gourds.

Such is the economic impact of hybrid seed companies on the local economy that it is common to find homes bearing homage to them. A seed company’s name inscribed in concrete suffixed with the word ‘krupe’ (benevolence) on the forehead of concrete homes painted in bright Vaastu-compliant colours ranging from parrot green to lemon yellow and Barbie pink isn’t a rare sight.

Hybrid hero

All of it is thanks to Manmohan Attavar a pioneering horticulture scientist and entrepreneur who must rank alongside MS Swaminathan and Verghese Kurien in the pantheon of modern India’s agriculture renaissance figures.

Everything on our plate today is a result of hybrid crops from cereals such as rice and wheat to ‘desi’ tomatoes to vegetables such as brinjal and gourds that we consider ‘indigenous’ because of their origins in India.

Hybrid crops are created by crossing two different but related plants to get the best traits of both parents, like two different varieties of tomatoes to create an offspring with desirable traits such as higher yields and resistance to a specific disease.

The science of plenty

Hybrid seeds became commercially important in the early to mid-20th century. The development and commercialization of hybrid seed varieties gained momentum in the 1930s and 1940s, with major advancements in crops like corn, cotton, and vegetables. This led to the widespread adoption of hybrid seeds, which significantly contributed to the Green Revolution and the increase in global agricultural productivity during the mid-20th century.

Don’t mistake them for genetically modified (GM) crops that involve altering the genes of a plant in a lab. For Instance, the genetically modified ‘Golden Rice’ was created by adding to the rice genome a gene from the daffodil plant to increase 20-fold beta-carotene levels in rice. Hybridization not only increases productivity but also ensures uniformity of produce, better quality and longer shelf life.

Mamnohan Attavar was born in 1932 in Karkala, a small town on the southern coast of Karnataka. He took up an unfancied course in horticulture at the agriculture college in the northern Karnataka town of Dharwad and earned a PhD in the US. With a loan of $14,000 from Chicago’s Ball Seed company where he had trained, Attavar set up a company in 1965, based in Bengaluru called Indo-American Hybrid Seeds (IAHS) that produced hybrid petunia flower seeds from the city for the US market.

First bloom

In fact, attempts to master hybrids began with flowers.

In 1716, Thomas Fairchild, a nurseryman in London was the first to scientifically produce an artificial hybrid flower known as Fairchild’s Mule. It was a cross between a flower called the sweet william and a pink carnation. He did this by taking pollen from the sweet william with a feather, and brushing it onto the stigma of the pink carnation. This was long before the science of genetics was established. Fairchild’s Mule preceded the firm scientific grasp of the idea of plant sex.

The concept of plant reproduction had been understood by humans for centuries, although not necessarily in the way we understand it today in scientific terms. Ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptians and Greeks, had some knowledge of how plants reproduced, often associating it with male and female principles or gods.

However, the scientific understanding of plant reproduction, including the roles of male and female parts in flowers and the mechanisms of pollination and fertilization, took shape only in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist best known for his work on taxonomy —the standardized, scientific way of naming and categorizing species, homo sapiens, for example–made substantial advancements in the 18th century in understanding the reproductive structures of plants. Linnaeus ascertained the roles of the male and female parts that coexisted in flowers.

A fruitful partnership

As business grew, Attavar approached Karnataka’s legendary horticulturist MH Marigowda for help to replicate the lessons learnt creating hybrid flower seeds for the US market to ring in a vegetable revolution right here in India.

Marigowda, with a PhD from Harvard was the then Karnataka’s director of horticulture who set up HOPCOMS, a pioneering cooperative that linked vegetable farmers to urban consumers. Marigowda supported Attavar by giving him access to polyhouses in Bengaluru’s iconic Lalbagh to experiment growing hybrid vegetables. Marigowda’s contribution is such that he is regarded as the ‘father of Indian horticulture’ and his birth anniversary on August 8 is celebrated as ‘Horticulture Day’ in the country.

In 1973, Attavar’s firm IAHS produced India’s first hybrid capsicum called Bharath and a variety of tomato called Karnataka. That’s why in many parts of India, the oblong variety is still popularly known as ‘Bangalore’ or ‘hybrid’ tomatoes, even if what is considered desi (globe-shaped and juicier) is a hybrid too.

While we can thank the Portuguese for introducing the fruit to India, without Attavar’s hybrid tomato revolution, Indian food as we know it—from rajma masala to rasam and ‘pink’ sauce pasta–may not taste as it does.

Then came other hybrid vegetables and even chillies. The popularity of red chilli varieties like Guntur Teja and Byadagi are the result of a post 1970s proliferation of hybrid seeds.

“My father identified Ranebennur as a hub for hybrid seed production at around 1979, and all the companies that you see today followed him,” says Santosh Attavar, the chairman of Indo-American Hybrid Seeds. Manmohan Attavar, a Padmashri awardee, died in 2017.

One-time wonder

Growing a crop for seeds is tougher than for food. Breeding hybrid seeds is even more complex.

In popular imagination, the food that we eat is the result of farmers saving a bit of their crop of say paddy or brinjal to convert it into seed for the next season. This method called the ‘farmer saved seed’ is how agriculture has been practiced from the time humans learnt to domesticate crops.

Farmer saved seeds maybe useful for subsistence farming, but the modern science of hybridization is inevitable to feed 1.4 billion Indians not to forget a global population of 8 billion.

Informal seed production can be like playing Russian roulette.

Farmer saved seeds may not have the same level of genetic uniformity and consistency as commercially produced hybrid or improved seeds. This variability can lead to inconsistent yields and poor disease resistance.

And over time, these seeds when continually replanted, lose their vigour. Hybrid seeds on the other hand cannot be reused at all.

The National Seed Association of India (NSAI) estimates that hybrids account for more than a third of the Rs 25,000 crore organized Indian seed market, not counting the farmer saved seeds and the informal. The hybrid vegetable seeds market is about Rs 2500 crore-3000 crore.

Blessed by geography

Back in the take 1970s when hybrids were only restricted to rice and wheat thanks to the Green Revolution, Attavar identified Ranebennur as the ideal place for large commercial production of hybrid seeds. Several factors worked in its favour. Chief among them was the climate and geography. Of the 10 agroclimatic zones of Karnataka, Ranebennur, located in the Haveri district is classified as a northern transition zone.

A transition zone is sandwiched between two different climatic or agricultural zones—in this case between the state’s northern plains and the drier southern plateau. Transition zones have a climate that share traits of the regions they separate, and can have microclimates, where local conditions differ from the broader climate pattern. This makes them suitable for growing a wider variety of crops across both the dry and wet seasons.

While a region such as Bengaluru is on average about 4⁰C cooler than Ranebennur, it is also much wetter with nearly 1000mm of annual rainfall compared to the latter’s 600mm. Seed production requires needs dry weather. Tomatoes for instance grow best under day and night time temperature of 21-25⁰C and 15-20⁰C respectively with humidity less than 60%.

Another reason why Attavar chose Ranebennur was because the average landholding of farmers here was smaller. Seed production is not only is labour intensive, but also needs hands-on every day attention. Smaller holdings allow farmers to be more attentive.

Beginnings of a boom

“He went from farm-to-farm convincing people to shift towards hybrid seed production,” recalls Santosh Attavar.

Assured procurement of seeds and better returns than producing crops for the commercial market was an attractive proposition for many progressive farmers. The tougher part however was training them in a process that required the skill and precision of a surgeon, the delicate craftsmanship of a goldsmith and a factory work floor manager’s attention towards quality control.

What Attavar started with 14 contract farmers in five villages around Ranebennur has now grown into business in the region involving more than 500 companies and several lakh farmers.

A hybrid plant is first perfected in the labs and R&D fields of the organization that wants to commercialize it. Let’s take the example of tomatoes, one of the most important hybrid seed crops in Ranebennur. Scientists begin by identifying the male and female parent lines or varieties whose specific traits such as fruit size, taste, resistance to specific diseases or climatic conditions they want the progeny to carry.

The fruits that are born out of this marriage solemnized by scientists are called the ‘first filial generation’ or F1 hybrids. The creation of a new commercially viable hybrid through this complex process of trial and error, field experiments and regulatory approvals typically takes about 7-10 years. Once perfected and approved, companies rely on farmers to produce the F1 hybrid seeds at a commercial scale by giving them access to the male and female parent lines.

A delicate operation

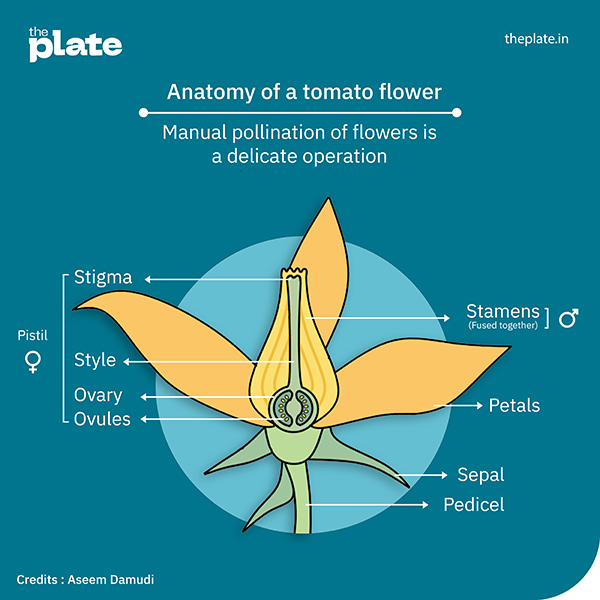

To grasp the complexity of the process of hybrid seed production, we must begin by understanding the anatomy of flowers.

In botany-speak, tomatoes belong to a class of plants that produce the ‘perfect flower’, that is, those with both male and female reproductive organs within the same flower structure. In other words, it has both stamens (the male parts, which produce pollen) and pistils (the female parts, which contain the stigma, style, and ovary for seed production) in a single flower.

Plants like cucumber and watermelon produce ‘imperfect flowers’ where pollination takes place from the male flower to the female.

In the tomato flower, mustard yellow and barely half the size of a fingernail, when dust-like pollen from the male sac called anther comes into contact with the stigma, an elephant snout-shaped female organ a fraction of the size of a pinhead resting on a stalk thinner than a toothbrush bristle, called style, reproduction begins. Facilitated in nature by insects such as bees or wind, this process is called self-pollination.

However, to produce hybrid seeds, self-pollination has to be prevented and the floral intercourse of stigma of the chosen female line and pollen from a different male has to be performed by human hands.

Seed farmers begin by emasculating, or removing the male anther sacs containing pollen using sterilized surgical forceps from the flowers of the female plant line before they being to bloom. When in bloom, natural self-pollination cannot be prevented. Workers wear a plastic ring around their middle finger that has another very tiny ring attached. That’s dipped into a small box containing pollen from the male line and dabbed onto the stigma.

Assured income

Companies such as IAHS usually only give farmers access to female lines and not the male parent to avoid others from stealing the pair. Only the pollens from the male lines are provided to the farmers.

Every tomato plant produces about 120 flowers; one unit (a quarter acre) of hybrid seed production has hundreds of plants; and this mating exercise has to be performed on every flower. Farmers need to ensure that of the 120 flowers on each plant, only 45-60 fruits get formed. More tomatoes mean greater burden on the plant’s physical resources and poorer quality fruits and seeds.

The difficulty of doesn’t end there. The hybrid units have to be at least a 100m away from commercial tomato fields to minimize cross pollination. Polyhouses offer better production but increase cost.

Timing matters too. Flowers need to be emasculated between 2-6PM and hand pollinated between 8-11AM for best results. And results matter for both farmers and the companies that contract them to manufacture hybrid seeds.

Every quarter-acre unit of hybrid tomato seed farm needs about 20 labourers working the whole day for a month during the pollination season post August. The peak seed production happens between November and January.

“For more than two decades, hybrid seed production was the ticket to prosperity for thousands of farmers in Ranebennur. Their lifestyle has completely changed,” says BM Somashekar, who runs a small hybrid firm called SB Seeds he founded in 2000 when the hybrid seed business had begun to boom.

Almost all of the hybrid seed production in Ranebennur happens under a contract between companies and farmers. Farmers contracted directly by large companies or their intermediaries are given the seeds of the female parent lines and part of the money in advance to help them managed the resource intensive operations. Companies in turn can only sell hybrid seeds that that pass stringent quality checks.

“Seed production is two to three times more profitable for us than growing for the commercial food market. Food market prices fluctuate wildly and we can never time the market. Here there is greater income stability. Germination ratio and hybrid vigour are two of the most important parameters for us. Seed farmers are paid in full only if the germination ratio is above 95% [if 95 out of a hundred seeds from a batch sprout in the nursery] and the productivity under test conditions good. It’s harder work, but a high-reward business,” says Maltesh, a hybrid seed farmer in Ranebennur.

If the germination ratio falls below the government mandated levels, the batch of seeds ought to be burnt by the company in the presence of the contracted farmer.

Farmers for their part have to harvest the fruits, extract and process the seeds and supply them dry to the companies. One unit of a tomato seed farm produces between 25-40kg of seeds.

An acre of commercial tomato crop needs not more than 20 grams of good quality hybrid seeds at a cost of about Rs 10,000. In horticulture seeds constitute about 5-7% of the production cost.

Seed stealers

The stakes are high for both farmers and the firms that contract them. Even a small oversight on the farmers’ part could potentially damage the entire batch of seeds in a unit. Company executives check on the progress of the crops and if the prescribed procedures are followed at least twice a week.

But there’s another reason too. Cross purchase of seeds is rampant. Unscrupulous agents lure farmers under contract with a company that’s painstakingly developed a new hybrid to sell them the seeds on the side at a hefty premium.

“Even if the company closely monitors production, the farmer can say he could only harvest 45kg of the seeds instead of the estimated 60kg and sell to shady operators often at thrice the price. These fly-by-night companies sell the seeds developed by companies at a huge investment under their brand,” explains Somashekar of SB Seeds.

Untapped potential

Unethical business practices aside, the lack of intellectual property rights protection for seed companies in India cripples Indian private sector R&D investments. Multinational companies too are wary of introducing their new lines of seeds. What they sell in India is often seeds that are a few generations older than those sold in other markets. That’s one of the reasons why Indian seed research remains heavily reliant on public sector seed research.

“In India many great scientists continue to do remarkable work. But what is the motivation to innovate. Even when I know my company’s material is being sold in the market by someone else, I can’t do much to contest that,” says Attavar.

While that maybe a nationwide problem, Ranebennur’s hybrid ride is getting bumpier.

“The climate is becoming more unpredictable. Over time if you keep growing the same crops at a place there is disease pressure and a buildup of pest attacks. Also, with the younger generation leaving agriculture for jobs in cities, there is a shortage of skilled in seed farmers,” says Manjunath Kulkarni, regional production manager (Karnataka), Kalash Seeds, a company headquartered in Jalna, Maharashtra that sources vegetable seeds from thousands of farmers in Ranebennur.

Indeed, many companies have begun shifting production to Koppal, some 125km to the northeast in Karnataka, or even to Jalgaon and Jalna in Maharashtra.

According to the World Bank, India imports seeds worth $850 million annually from countries such as The Netherlands, Italy and Thailand. That level of import dependance on something as fundamental as seeds is troublesome for a large agricultural nation.

“There is now a major government push towards ‘make in India’ and self-reliance. That should also extend to seeds because it is the foundation of food systems. India has plenty of arable land and 15 agroclimatic zones. With enabling policies, we can create many hubs like Ranebennur across the country and not just be self-reliant but also become a significant exporter,” says Attavar.

Very nice article, proud to be from Ranebennur area and kudos to M Attavar sir💐

Nice article. Nicely explained. Good to be part of seed production from this area.

“Farmer saved seeds may not have the same level of genetic uniformity and consistency as commercially produced hybrid or improved seeds.” This is an unverified assumption. Seed companies can promote their products, but not by rubbishing what farmers have been doing.

On the other hand, I would encourage the author to continue this story and explore how much of Rs.500 crores turnover is going into farm labour and farmers kitty. Ultimately, Ranebennur story is continuing because these people toil and sacrifice. Behind this ‘incredible’ story lies the pitiable conditions of these critical sections.

Farmer saved seeds have the same genetic uniformity and consistency of hybrids only if it is a self pollinated crop and there is no physical mixture. Unfortunately we have only a very few vegetable crops which are self pollinated. We need not discourage farm saved seeds. Urban homesteads growing vegetables for their household use can very well grow them. But for commercial cultivation we need good hybrids

Very often the farmers divert the yield to general markets if the prices are more fetching that the seeds that they have contracted to make. Like tomatoes for example that were selling for Rs100 or more per Kg recently, w’d fetch them windfall profits compared to the price they get if they make seeds and supply to the Company with which they have the contract.

Contracting Companies get devastated when they invest huge sums and don’t get the supply of seeds as per the contract ! Little c’d be done to enforce their rights legally…….

Nice article, feeling proud of being a part of IAHS.

Very good Article,Seed Hub of Asia as written on NH-4 poona- Bangalore high way before entering in to Ranebennur..

Myself being Agriculture graduate worked in Mahyco seeds Ltd nearly 1.5 decades in developing seed

production aspects of all crops with team 25 agricultural graducates step by step covered nearly 400 villages and trained the farmers in producing seeds,I am happy and feel proud to share the article.

Very informative article. Even though I am a agriculture post graduate & working in Seed Industry R&D for the past 6-7 years never heard about Dr. Manmohar Attavar. Thanks for the detailed information on hybrid vegetable seed industry inception, growth & development in India.

Very good article, covered all the aspects of seed production from start to end. I have been here in Ranebennur since 1997 doing seed production working for 3-4 seed companies. But now started my own firm and producing vegetable seeds to many companies contracting with farmers. It is becoming very challenging to get high quality seeds now due to arrival of new pests and diseases and increased cost of seed production.

Very good Article and Happy to share that being part of seed production and worked for 2.0 decades in Mahyco seeds ltd and zuari seeds Ltd. In Ranebennur

RANEBENNUR recognized as SEED HUB oF ASIA ,written on NH-4 Bangalore-poona Highway before entering in to Ranebennur.

Ranibennur is 300 KM North West of Bangalore not North.

so much info here… super

It is true by facts that the strategic location, strategic move by farmers towards seeds production, fine tuned labour workforce, economics around seeds & increased infrastructures for these have led to a mature setup to be Bharath’s vegetable seeds hub.

My father in law ,Mr Sripad Hiregoudar from Rannebennur,who passed away in 2008,toiled alongside Mr Attavar

Very nice write-up My friend M.S.Chandrasekhar is connected to Rannibannur for the last 20years a great place Mecca of hybrid seeds

One of the unspoken challenge is how these seed companies take farmers to their advantage. They pay very unfair amounts to produce these seeds and make big profits. There is nothing wrong in making profit ,but I feel they are only exploiting low cost labour

Very informative article.

Seed production has really increased the farmers income and it has put them out of the middleman loans significantly. Farmers are more independent and pay no commission on sale of seeds on contract which is beneficial to farmers.

Cotton started failing after dch32 started going down, many farmers switched to seeds thus saving the whole farmin community there.

Being a Banker who had the RO in Hubli was travelling to Ranebennur often. Can say that every house was like a Cottage Industry producing seeds. Paying Tributes to late PadmaShri Manmohan Attavar and Dr Marigowda for their stupendous efforts in developing Hybrid seed production, the IAHS company deserves all the praise for its efforts in putting RANEBENNUR as Seed Capital of Asia. While price of Veg vary with demand / supply this sector We hope farmer will be rewarded adequate for his strenuous efforts and encourage budding talent from neighbour areas including Kolar/ Chikballapur to take up this. Once again Thanks for the beautiful article. 👍💐🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🍅🙏

Thanks to access to continue

Very nice information

Thank for the article

When we talk about Vegetables seed production hub, it is Ranebenur which is emerged as World hub for Vegetable contract seed production for many National and international seed companies. The climate for Vegetable Seed production is suites very well where seed setting percentage is higher than other places.

Even there are seed production organisers who can produce the leading segment of required vegetable seeds in Renebennur Area .

Article is really absorbing and I’m glad to get informaton about

poorly known facts. Despite being from Karnataka, I was unaware how important Ranebennur has become. Kudos to Padmashri Dr Attari and to the farmers who have learnt and adopted these skilled, delicate, labour intensive methods to the betterment of their lives and the lives of all of us who reap the benefits today.

very interesting and hardwork of mr.Attvar…. we salute him for having such a vision that helped our country and society in production of seeds…..

Very nice appreciate the effort of pioneers and all the stake holders

This is Article is showing a mark of Success for seed growers and huge seeds production still untapped potential , were importing of seeds will diminish gradually. Though we miss Dr Manmohan Attavar , the effort of contribution is enlightening the seed growers.

Excellet article on the evolution of hybrid vegetable seed production (especially Tomato) around Ranebennur in Karnataka.

Dr Manmohan Attavar, a great visionary agricultural scientist deserves all the credit for the hybrid vegetable seed revolution in India.This was followed by Mahyco and Syngenta(then Sandoz) and many other companies . With their dedicated hard work the Ranebennuru farmers made this all possible.I am proud to be part of this successful team strating from Mahyco to Syngenta.

[…] the full story here about how a pioneering Indian scientist-entrepreneur turned a non-descript town in Karnataka into […]