The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

Populist, consumer-focussed subsidies are making several state milk cooperatives unhealthy. A cash-rich Amul could certainly benefit.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

The hardcore anti-BJP Opposition politicians seem to have discovered a new bogey business from Gujarat, whose name begins with A, to add to list comprising Ambani and Adani. Amul, one of India’s most beloved brands and a Rs 72,000 crore co-operative giant owned by the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) has become a frequent fly in the unpasteurised milk of Indian politics.

On May 25, 2023, while on an official visit to Singapore and Japan, MK Stalin, the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister released on Twitter his letter to Amit Shah, the Union Home Minister and Minister of Cooperation opposing Amul’s procurement of milk from the northern districts of the state. “Recently, it has come to our notice that Amul has utilised their multi-state co-operative license to install chilling centres and a processing plant in Krishnagiri district and planned to procure milk through FPOs [Farmer Producer Organisations] and SHGs [Self-help Groups] in and around Krishnagiri, Dharmapuri, Vellore, Ranipet, Tirupathur, Kancheepuram and Tiruvallur districts of our state,” he wrote.

Spilling the milk of cooperation

This he argued would create unhealthy competition among milk cooperatives in India and asked Shah to direct Amul to stop all procurement from Tamil Nadu Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation or Aavin’s (its commercial brand) milkshed area.

“It has been the norm in India to let cooperatives thrive without infringing on each other’s milkshed. Such cross procurement goes against the spirit of ‘Operation White Flood’ and will exacerbate problems for consumers given the prevailing milk shortage scenario in the country,” he added.

Fearing a local ‘behemoth’

This comes barely a month after Amul’s decision to sell its fresh milk and curds in Bengaluru was used by the Congress to clabber the electoral milk in Karnataka. Congress and Janata Dal (Secular), then in opposition, claimed that it was part of the Centre’s plans to weaken Karnataka’s own beloved cooperative milk brand Nandini for it to be eventually gobbled up by Amul.

“Milk has clearly become a subject to settle political scores. The large number of farmers engaged in dairy farming makes them a valuable vote bank in any state. Stalin has seen the Congress use the issue cleverly in adjoining Karnataka and could be trying to replicate it,” says Kuldeep Sharma, a veteran dairy technologist who runs a dairy consultancy. Amul already procures milk from two other southern states Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

Milk has clearly become a subject to settle political scores. The large number of farmers engaged in dairy farming makes them a valuable vote bank in any state. Stalin has seen the Congress use the issue cleverly in adjoining Karnataka and could be trying to replicate it.

The issue in Karnataka was about Amul expanding its sales while Tamil Nadu is peeved by it procuring directly from the state’s farmers. The common theme here, however, is the portrayal of Amul as a corporate marauder in a cooperative’s cloak.

While Amul’s commercial heft (it is the among the 10 biggest milk processors in the world), the war chest for expansion and pan-India brand recognition lends credibility to such a caricature, it would at the same time be a lazy explanation to shy away from a serious examination of the health of India’s dairy sector and the cooperative movement becoming a pawn in the politics of populism.

The roots of a revolution

It is instructive to go back a bit in history and understand the birth and success of the cooperative movement.

The Green Revolution is considered one of the most important events in the history of modern India. But the gains from the White Revolution are far more spectacular. The Operation Flood or the White Revolution set in motion in 1970 has now made India the largest milk producer in the world.

The 220 million tonnes of milk it produced in 2022 is about 24% of the global output. Indians have access to 440g of milk a day, far more than the recommended daily average of 387g. Milk is by far the most valuable component of Indian agriculture (bigger in value than rice and wheat) and the dairy industry accounts for nearly 5% of the country’s economy.

In 1970, the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) officially launched ‘the billion-litre idea’ with the goal to take India’s dairy industry from a drop to a flood. It was to become the biggest dairy development programme in the world.

Operation Flood would work in a completely decentralised fashion. Milk would be collected by people of the villages; at the district level the dairies would be handled by the district unions; at the state level the marketing would be taken care of by the marketing federations. It was to ensure that the entire value chain remained in the hands of the small farmers. In effect, the White Revolution involved the replication of the “Anand/Amul Model” countrywide.

The White Revolution broadly rung in three fundamental changes. One, it created a nationwide chain of milk-specific cooperatives that could source milk from a network of millions of small farmers owning as few as two or three animals. With access to big volumes of milk, the cooperatives could invest in large processing infrastructure.

They set up small rural collection centres with milk chilling and basic quality check equipment where farmers could sell their output twice a day. The quality checks ensured that farmers’ milk was tested for the fat content, and they were paid fairly in accordance with quality not quantity of milk. At once, it brought in a level of quality assurance the country’s unorganised milk sector was not used to.

Two, the White Revolution introduced new technologies that improved milk productivity. Native Indian cattle breeds such as Sindhi were cross-bred with European Jersey, Brown Swiss and Holstein-Friesian cows. The cross-bred cattle could withstand the hot and tropical Indian conditions, and yet produce more milk. This could only be accomplished by making veterinary services and techniques such as artificial insemination more accessible.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, an extremely perishable produce of farmers was effectively linked to urban markets. All regional cooperatives branded their dairy products—from Amul in Gujarat to Sudha in Bihar, and a national marketing campaign around milk and its benefits as a cheap and accessible source of nutrition helped create sustainable demand.

Thinning milk

But now, some experts contend, lack of attention to breeding programmes and mindless populism has pushed India towards the end-point of the gains from the White Revolution. There are legitimate concerns about India’s milk production plateauing.

“Tamil Nadu complaining about Amul today is like a person crying about theft after leaving their house without a lock. It began with Kerala and is spreading elsewhere. In the guise of subsidising the farmer with higher prices, the cooperatives controlled by the state governments have been subsidising the consumer with cheap milk. It leaves them with no money to focus on cattle breeding R&D. When two pure bred cows—Indian and exotic—are crossed you get higher hybrid vigour from the first generation or F1 hybrids [the best traits of the pure-bred parents. Hardiness from Indian lines and increased productivity from foreign breeds like Jersey]. When you cross the subsequent generations indiscriminately, productivity is bound to get affected. We have simply not paid attention to our native breed stock,” says Rajeshwaran Selvarajan, professor, public policy, Development Management Institute, Patna, who specialises in the dairy sector.

Tamil Nadu complaining about Amul today is like a person crying about theft after leaving their house without a lock. In the guise of subsidising the farmer with higher prices, the cooperatives controlled by the state governments have been subsidising the consumer with cheap milk.

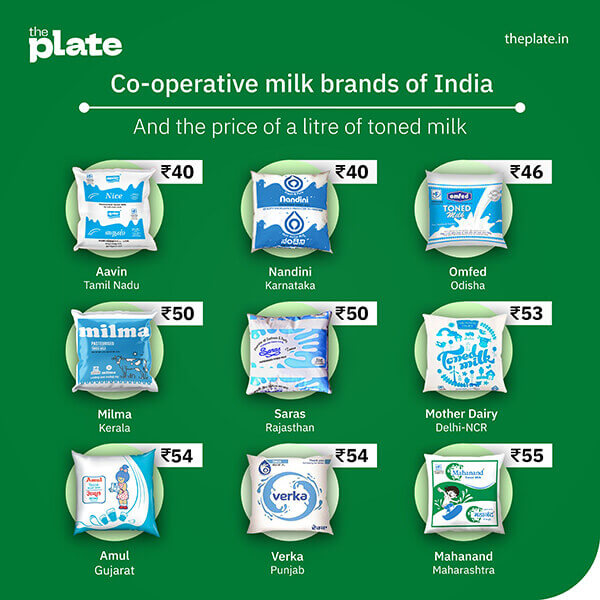

This is how state-level populism has been chipping away at of Indian agriculture’s bright spot. Tamil Nadu’s Aavin for instance procures cow milk from farmers at about Rs 34/litre and the retail price of its standard toned milk is Rs 40/litre (the lowest in the country alongside Karnataka). Keeping consumer prices artificially low results in not just low income for farmers but also throttles the private sector. Private dairies have to pay at least Rs 2 more than the state cooperatives to convince the farmers to sell to them, offer superior agronomy services to retain their loyalty, and then compete in the retail market.

During the recent Karnataka election campaign, Rahul Gandhi promised dairy farmers that the state procurement subsidy for milk would be raised to Rs 7 from Rs 5. Such subsidies amount to more than Rs 5000 crore annually.

The scourge of subsidy

“Subsidy is a cancer that affects the entire industry. It accounts for anywhere between 7-20% of the price of milk across states. How can the private sector compete with such a disadvantage? The states can account for it as a recurring loss and finance it. In fact it is not even going to the farmers, but ending up with consumers. If they had invested that subsidy over a decade in improving productivity and infrastructure, the whole of India’s dairy sector would have benefitted,” said RG Chandramogan, the founder and MD of Hatsun Agro, the largest Indian private sector dairy firm at the Food Conclave organised by the Telangana government recently.

In fact, in states such as Maharashtra, Gujarat and Punjab for where the retail price of a litre of milk is at least Rs 15 more than in Tamil Nadu or Karnataka, the income of farmers too is higher.

So, when Amul procures from Tamil Nadu, the farmers stand to gain at least Rs 2/litre with increased competition. Why is it such a bad thing?

“While its good for the farmers, I can understand the concerns of states like Tamil Nadu. Amul can’t simply use its financial muscle to enter new markets. They should have a dialogue with state cooperatives instead and reassure them on how they will strengthen the local milksheds. That would be in the spirit of cooperation,” says Kuldeep Sharma.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.