The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

The story of India’s journey from below-subsistence level dairy farming to becoming the world’s largest milk producer.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

In 1942-43, several Britishers living in Bombay suddenly fell sick. Investigations into the matter revealed that the chief cause was the milk they were consuming. A sample of milk was sent to UK for testing. The test result read: “The milk of Bombay is more polluted than the gutter water of London.” Consequently, the British government was forced to come up with a plan to improve the quality of milk coming into the city.

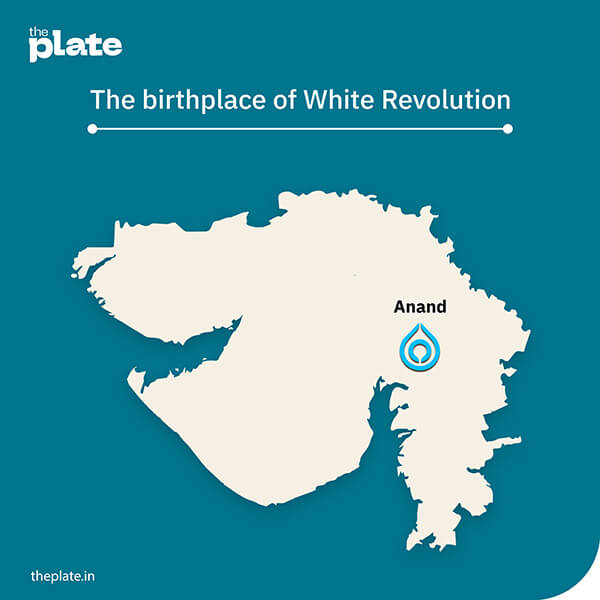

The search for a reliable source of milk in large volumes led the Bombay government to Kaira district (now called Kheda in Gujarat, but then part of Bombay Presidency) some 330 kilometres to the north.

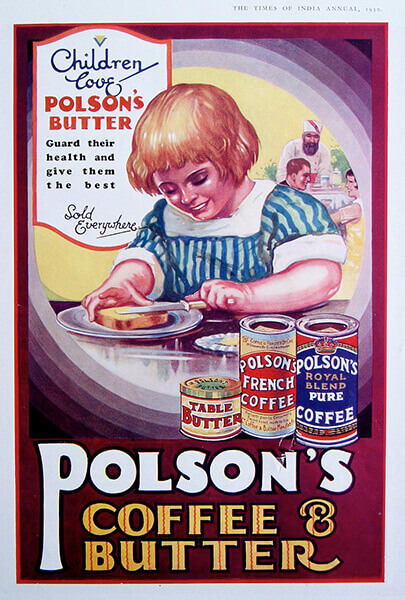

By then Kaira already had the reputation of being a milk hub of sorts. Around 1895, an Englishman had started a butter factory some 15km north of Anand in this district. A German had also set up a casein factory nearby. Casein is the milk protein which in the early 20th century was used to make plastic. Casein plastic was used to make products like buttons and fountain pens. In 1926, a Parsi businessman Pestonjee Edulji had built a factory to make butter that was sold under the brand name Polson in the region. Polson was to be a household name before another brand from Anand killed it off.

The Bombay government asked Polson if it could supply milk every day to the city from Kaira across 330km. Something like this hadn’t been done in India. Polson pasteurised the milk in its plant and sent it in cans wrapped in gunny bags drenched in cold water. With this pioneering experiment of shipping liquid milk across such long distances in 1945 was born the Bombay Milk Scheme.

Polson had the monopoly on milk supply; Bombay offered a large readymade market for the farmers’ produce; and consumers had access to better quality. It was to be a win-win for all involved. Except it wasn’t.

The farmers of Kaira increased production to such an extent that the district had already become the largest and best-known milk producer in the entire region.

But the farmers very soon realised that only a fraction of the consumer price reached them as Polson and its contractors pocketed most of the money.

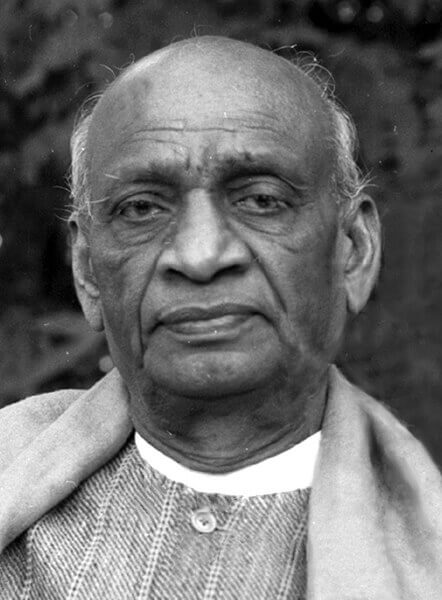

Kaira’s farmers recounted their story of exploitation to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel who belonged to the same region. Patel’s answer was that the farmers had to be in control of the entire milk value chain—from production to marketing. He asked dairy farmers to organise milk cooperatives, which would give them control over the resources they generated. He assigned Morarji Desai, his deputy, to coordinate the effort. Desai identified a young freedom fighter and the vice chairman of the Kaira District Congress Committee, Tribhuvandas Patel, to head the cooperative.

Despite the formation of farmer groups, the problem of exploitation persisted. Polson would somehow find a way to pay farmers less. It would complain of flies in the milk or pay them less on account of lower fat content in the milk.

When Tribhuvandas Patel and farmers went back to Sardar Patel, his battle cry was “Remove Polson”. But to do that the entire dairy movement in the district had to be united and, above all, they had to own their dairies. Since it was 1945, he warned the farmers that the British would not take such a move kindly.

By January 1946, the farmers had decided to take on Polson and the government. They decided not to sell any milk to Polson and that a cooperative would be set up in every village of Kaira. A union of these cooperatives headquartered in Anand would process and market the milk. BMS rejected the proposal. The farmers of Kaira went on a strike for 15 days. They were happy to pour the milk on the streets rather than sell a drop to Polson. The strike crippled Polson and BMS went bust.

The British government relented hoping that bunch of Indian buffalo farmers and their leaders in Gandhi caps didn’t know a thing about dairy farming and would come crawling back to the old arrangement when their experiment inevitably bombed.

Through 1946, Tribhuvandas patel walked from village to village persuading farmers of Kaira to form cooperative milk societies. By December 1946, the Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers Union Limited (KDCMPUL), the mother of Amul was born. India’s biggest market, Bombay, was now directly linked to the farmers of Kaira.

In 1946, a young engineer called Verghese Kurien was selected by the British government in India to study in Western universities and gain a Master’s degree. Kurien belonged to a wealthy and privileged Kerala Syrian Christian family. His grand uncle John Matthai was to become the independent India’s first Railway Minister. While young Kurien was interested in metallurgy and nuclear physics, he was chosen for a Government of India’s agriculture ministry sponsored degree at Michigan State University, then considered the best place for dairy research in the world.

While Kurien had earned a master’s degree in metallurgy with some mandatory courses on dairy technology, upon his return to India, he was posted in Anand as a researcher in the Government India creamery in 1949. Disinterested in his job, Kurien was looking for the nearest exit.

The Kaira Cooperative’s plant was in the same campus as Kurien’s office. In his spare time, and there was plenty of it, he frequently helped fix the outdated 1910-era machinery it used.

After a routine repair job, Kurien told Tribhuvandas to scrap the rusty plant and build a new one if the cooperative had to have any chance of survival. Tribhivandas took up the challenge of arranging the Rs 40,000 it took for the new plant and asked Kurien to build it. It was merely an unpaid side gig for Kurien. When the plant was built and Kurien’s resignation from the government job finally accepted, Tribhuvandas offered him the job of the general manager at KDCMPUL in 1950. It would be tempting to say the rest is history. It wasn’t as easy.

By 1952, against all odds, KDCMPUL was supplying 20,000 litres of milk compared to 2000 litres in 1948. Anand’s farmers were supplying milk to Bombay’s consumers in insulated railway vans.

The success of Kaira cooperative movement was by now in no doubt. But a problem of demand-and-supply cropped up as the Kaira-Bombay market linkage grew stronger. Buffaloes produced twice the milk in winters than summers. There was no market for the excess winter milk, while there was no way to store it for supply during the lean summer months.

The only solution was to set up a processing plant to convert the extra milk into products like butter and milk powder. While the Western world knew how to turn cow milk into powder, there was no way to make buffalo milk into reconstitutable powder.

Thankfully, Kurien’s mate at Michigan State University and ace dairy technologist Harichand Dalaya was at hand. Dalaya hailed from a prosperous Yadav family in Uttar Pradesh that ran a successful dairy business in Karachi with 300-odd Sindhi cows. The family had enough money to send him to Michigan before it was forced to wind up operations in Karachi post Partition. Dalaya invented a way to spray dry buffalo milk into powder when every single dairy technologist in the world had thought it impossible.

Dalaya’s invention paved the way for India’s first milk powder and butter plant that was inaugurated by Prime Minster Jawaharlal Nehru on October 31, 1955, the birth anniversary of Sardar Patel.

By 1956, Kurien realised that Kaira Cooperative’s increased milk productivity needed an even bigger market, that in turn needed better branding and marketing. A chemist at the Cooperative came up with the name Amul. It was a derivative of the Sanskrit word ‘amulya’ that meant ‘priceless’. It not just symbolised the pride of swadeshi production, was short and catchy and could be an easy acronym for Anand Milk Union Limited. In 1957 Kaira Cooperative registered the brand ‘Amul’ that would soon become one of India’s best-known brands.

On October 31,1964 when PM Lal Bahadur Shastri visited Anand on yet another birth anniversary of Sardar Patel, he asked Kurien to replicate the Anand model across India. Despite the support of the PM, the plan failed to take off due to bureaucratic meddling and turf wars within the government.

To fulfil the wishes of the PM, and in national interest, Kurien convinced the Kaira Cooperative that it should create The National Dairy Development Board without central government funding in 1965.

In 1966, Amul upped its advertising game. It hired an agency called the Advertising and Sales Promotion Company (ASP) with a mandate to knock Polson off from its perch as Bombay’s top butter brand. ASP’s art director Eustace Fernandes created the iconic Amul girl to take on Polson’s ‘butter girl’. It had also launched several milk powder, butter, condensed milk, cheese and baby food.

In July 1970, NDDB officially launched ‘the billion-litre idea’ with the goal to take India’s dairy industry from a drop to a flood. It was to become the biggest dairy development programme in the world.

Operation Flood would work in a completely decentralised fashion. Milk would be collected by people of the villages; at the district level the dairies would be handled by the district unions; at the state level the marketing would be taken care of by the marketing federations. It was to ensure that the entire value chain remained in the hands of the small farmers.

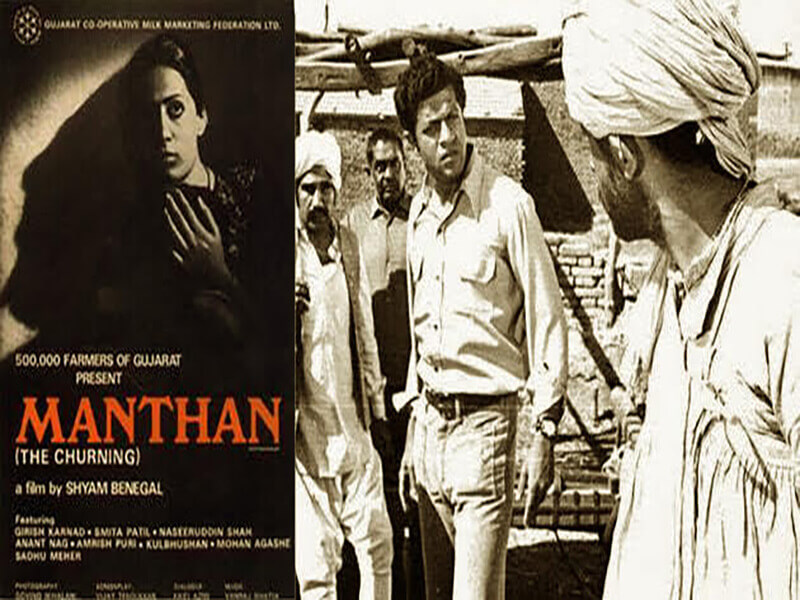

Manthan, a film based on Kurien’s efforts to collectivise Gujarat’s dairy farmers and the Operation Flood, directed by Shyam Benegal was released. Made on a shoestring budget of Rs 10 lakh funded entirely by the dairy farmers of Gujarat who contributed a rupee each.

The film starred young actors like Smita Patil, Girish Karnad, Naseeruddin Shah and Anant Nag and won several awards.

But Amul used it as part of its sales pitch to farmers to join the cooperative movement and drive home the message of the economic and social benefits of the cooperation.

The second phase of Operation Flood from 1981 to 1985. It was implemented with the seed capital from European countries and a Rs 200 crore World Bank loan. During this period, the number of milksheds increased from 18 to 136. Moreover, 290 urban markets increased the outlets for milk produced. By the end of this phase, a self-sustaining system of 43,000 village cooperatives covering 4.25 million milk producers was well established. Milk powder production increased from 22,000 tonnes in the pre-Operation Flood year to 140,000 tons by 1989. Direct marketing of milk by producers’ cooperatives increased by several million litres a day.

The third phase of Operation Flood, which lasted from 1985 to 1996, added 30,000 new dairy cooperatives to the 42,000 existing societies. The number of women members and women’s dairy cooperative societies increased considerably. This phase focused on assisting unions to expand and strengthen their procurement and marketing infrastructure to manage the increasing volumes of milk. Veterinary health-care services, feed and artificial insemination services for cooperative members were extended. Animal health and nutrition was the big focus area.

In 1998, India overtook the US to become the largest milk producer in the world.

The same year, the World Bank published a report on the impact of dairy development in India and looked at its own contribution to this. The audit revealed that on the Rs 200 crore the World Bank invested in Operation Flood, the net return into India’s rural economy was a massive Rs 24,000 crore each year over a period of ten years. Certainly no other development programme, either before or since, has matched this remarkable input-output ratio.

India remains the largest milk producer in the world with an annual output of 220 million tonnes. Milk is by far the most valuable component of Indian agriculture (bigger in value than rice and wheat) and the dairy industry accounts for nearly 5% of the country’s economy.

While the White Revolution helped India make enormous gains, the country’s milk productivity is still nowhere near global standards. In 2023, climate change, declining availability of fodder and creeping weaknesses in breeding programmes pose a challenge in retaining the advantages Operation Flood offered.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

You probably forgot to cover Military Farms and Government Milk Supply Schemes. They had their own role and are an important part of Dairying history of India.