The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

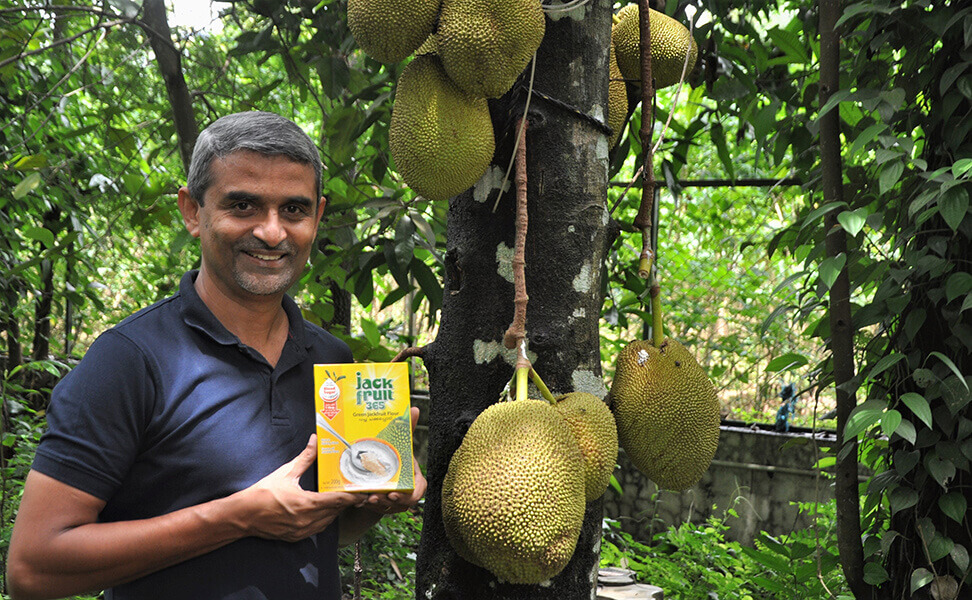

An ex-Microsoft executive has found a way to get healthy jackfruit into everyday Indian diet inspired by former Indian President APJ Abdul Kalam’s one-line brief to him.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

Startup ideas can strike you if you stare out of the window long enough.

James Joseph, 52, returned to India in 2007 after a stint in the UK and US as a director of executive engagement at Microsoft. He had wangled a deal with the tech giant to work remotely, out of a village near Aluva, a ten-minute drive from the Kochi airport, instead of its Bengaluru office in India, among other things, to be able to give his children a taste of the “slow life”. The arrangement worked out pretty well. Well enough for Joseph to win the firm’s ‘Employee of the Year’ award in 2010.

In 2013, at the goading of fellow Malayali Kris Gopalakrishnan, a co-founder and former CEO of Infosys, Joseph decided to take a year off from work and write a book called God’s Own Office: How One Man Worked for a Global Giant from His Village.

The sight of a giant jackfruit tree in the front yard every time he looked out of the window near his writing desk, and childhood nostalgia for the fruit inspired him to start-up a full-fledged business around it called Jackfruit365.

The company makes flour from raw or unripe jackfruit that can be added to chapati atta or idli and dosa batter without altering the taste while getting the benefits of jackfruit’s high fibre and diabetes-resisting qualities.

A wasted bounty

“Growing up in Kerala you are never too far away from jackfruit. There is an adage that one jackfruit tree in the backyard can extend a person’s life by ten years. It is so plentiful that people don’t even bother to harvest. It just drops to the ground and rots away. The big fruits are now such a nuisance that people are chopping jack trees off,” says Joseph.

While writing the book, he became determined to find a way to put this bounty of nature to more profitable use and give it some good PR.

In India, the home of the jackfruit, the biggest tree-growing fruit in the world, Indians say some terrible things about it, though most don’t know it exists. North Indians hate the ripe fruit for the smell they find unpleasant and, erm, reminiscent of excrement.

It looks frightful too—giant (weighing up to 15 kilos) and spiky. Experts would tell you that you must always run your palm over the fruit before buying one. When the skin is leathery and the spikes blunt, the fruit is ripe for consumption.

My daughter goes to a school with a jack tree that produces slightly sickly fruits with wavy instead of the usual round skin. The tree forms the axis of the communal dining area. Despite five years of familiarity with the tree, and now aged 14, she is still too scared to sup in its shade.

In the south, jackfruit has an exalted status. According to ancient Tamil literature, it is part of the divine troika alongside mango and banana; its wood is used to make the mridangam. Kerala officially declared it the state fruit in 2018. Karnataka’s coastal and hill regions, and the Tumakuru district to the north of Bengaluru jostle for the claim of producing the best jackfruits.

Bengal and Odisha too have a great tradition of jackfruit consumption. Yet, even in these parts, jackfruit gets so little love that we end up wasting almost half our output.

An image makeover

During the writing of the book, Joseph turned into a fulltime jackfruit evangelist coaxing chefs at fancy restaurants in Kerala to include raw jackfruit in innovative ways in a variety of dishes, conning his guests into believing it was some kind of animal protein.

“In India, the typical plate of even those who can afford a nutritious diet, comprises 50% carbohydrates in the form of rice or roti, 25% proteins and vegetables respectively. In fact, vegetables should ideally be 50% of our meal. We are addicted to a carbohydrate dense diet that is often at the root of many lifestyle diseases,” says Joseph.

His idea was if the west can eat Caesar salad, why can’t India get into the habit of eating chakka puzhukku [steamed raw jackfruit tempered with grated coconut, green chillies mustard and garlic], quite popular and still a staple in many parts of Kerala.

“I wanted to rebrand a commodity into a high-value product. If the rich start eating something, the poor too will want to,” adds Joseph.

The neutral-tasting chakka puzukku is essentially a vegetable salad rich in fibre, and a rice substitute that could be had with gravies like fish curry. Joseph’s book had a small chapter on all his experiments to mainstream raw jackfruit including selling burgers made with it.

Out of his admiration for the former Indian President, APJ Abdul Kalam, Joseph made sure to send the first copy of the book in 2014 to him. In November of that year, he got a call from Kalam’s office inviting him for a meeting in Delhi.

Of all the things in the book, Kalam was keen to find out more about Joseph’s work on jackfruit.

The President’s brief

Kalam was convinced a “Second Green Revolution” that matched the IT revolution held the keys to India’s progress. He was intrigued by Joseph’s ideas on making more out of a natural produce going to waste.

Joseph narrated to Kalam his now well-rehearsed script about raw jackfruit having 40% less carbs and two-to-four times more fibre than rice or wheat. “Kalam went silent for about three minutes. I was worried stiff. Then he said, a high-fibre meal always translates into low sugar absorption. That’s a given. There’s one new thing here: most fruits when unripe are acidic. Jackfruit is neutral. But do remember, in India, it’s easier to change religion than food habits. You are an engineer. Find a way to make the whole of India eat green jackfruit; the housewives are the most influential nutritionists, get them on your side. When you do that, I’ll personally come with you to every part of the country and campaign for your idea,” recounts Joseph.

This simple, yet powerful insight became a one-line product brief for Joseph. Could the idea be turned into something like adding iodine unobtrusively to common salt to tackle a public health problem at scale? After all, fortifying wheat flour with jackfruit might benefit not just consumers but also incentivise jackfruit farmers.

The challenge was accepted and within a couple of years, Joseph has found a patented method for dehydrating raw jackfruit and turning that into flour, and most importantly, a flour with the right binding factor that when added to rice batter would not make the dosa stick to the tawa, or a roti to break when mixed with atta. By 2017, the flour branded as Jackfruit 365 was in the market. Sadly, Kalam died in 2015 before Joseph could demonstrate the progress on his challenge.

Building evidence

Not just that, Joseph using his training and experience as an automobile engineer invented a patented device for mechanised, assembly line cutting and extracting of jackfruit pods—the biggest deterrent for even the fruit’s faithful.

“The labour cost of processing jackfruit is very high. Not many people want to handle such a latex-heavy, sticky and gummy fruit. Also, it ripens very fast. The buildup of sugar even in cut raw jackfruit accelerates, so it has to be processed very quickly. I went around the world asking industrial designers to come up with a scalable solution. The structure of jackfruit is different from others like apples. Each fruit has hundreds of bulbs of seed-containing flesh around a stringy core. Everyone gave up, and I had to come up with my own design,” he explains.

From the early days of his evangelism, Joseph was convinced about the anti-diabetic properties of raw jackfruit, but making such claims needed scientific validation and clinical trials.

“While the product was out, we were selling it without telling people the actual reason for buying,” says Joseph.

By 2020, the clinical trial conducted at the government medical college in Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, and its results published in the science journal Nature presented at the annual conference of the American Diabetes Association, allowed Joseph to explicitly make the claim about Jackfruit365 flour helping fight type 2 diabetes in 90 days by lowering blood sugar levels without breaking Indian advertising and food safety regulations.

Type 2, the most common form of diabetes, is a lifelong disease caused by a high level of sugar or glucose in the blood. Insulin is a hormone produced in the pancreas that transports glucose into the body cells where it is stored and later used for energy. With type 2 diabetes, the cells do not respond appropriately to insulin leading to what is known as insulin resistance. As a result, the cells do not get the necessary glucose to release energy.

When sugar cannot enter cells, a high level of it builds up in the blood and the body is unable to use the glucose for energy. This condition called hyperglycaemia leads to the symptoms of type 2 diabetes.

The ticking time-bomb called diabetes

According to a recent Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) study, there are more than 100 million diabetics and 136 million prediabetics in the country. Adults with diabetes have a two-to three-fold increased risk of heart attacks and strokes.

The ability to make a claim for the anti-diabetes qualities of the product, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when physical activity was low and health concerns peaked, turned Jackfruit365 an overnight success on e-commerce platforms such as Amazon.

Joseph’s sales pitch was that adding 30g, or a tablespoon per meal, of jackfruit flour per day to make idli batter or chapati atta could deliver a food item with pharma-grade efficacy.

The sales witnessed a hockey-stick growth. It was the third-biggest selling grocery item on Amazon after Maggi noodles and Tata Salt. According to Joseph, Jackfruit365 clocks sales of more than Rs 1 crore a month just on Amazon with a cumulative customer base of more than 500,000. The National Startup Award in the food processing category in 2020 also helped.

With nearly 1200 grocery and pharmaceutical stores across south India stocking the product, the demand was such that the company had run out of production capacity. It had to pause its marketing campaign. Joseph estimates that the processing capacity of about 1500 jackfruits a day or roughly 15 tonnes needs to go up to 60 tonnes shortly to keep up with demand.

“I wonder how much more popular jackfruit would have been if Dr Kalam was alive to make good his promise to me.” You might have to gaze out of the window to make a guesstimate.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

Innovation at its best. Well done Joseph. Hope we can find it more often in local grocery stores.

[…] The first is about James Joseph, an ex-Microsoft executive who found a way to get healthy jackfruit into everyday India… […]