The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

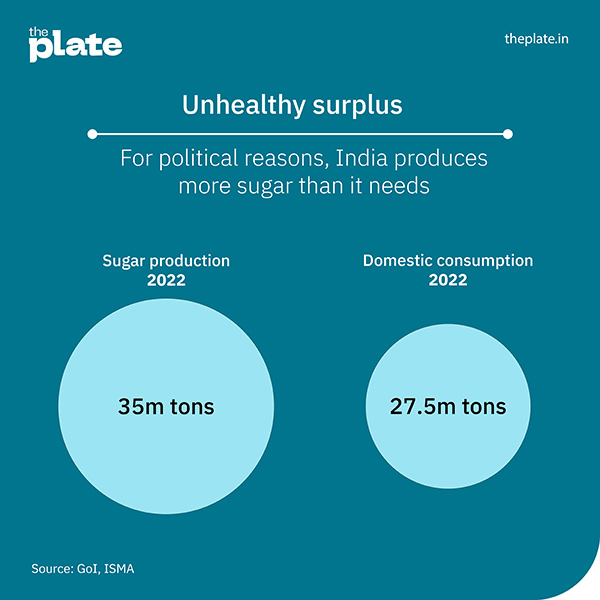

India produces way more sugar than it needs and eats more sugar than is healthy.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

The recent controversy around Cadbury forcing social media influencer Revant Himatsingka to take down a video on high sugar levels in the popular malted beverage mix Bournvita has shone a spotlight on branded food labelling and what exactly do the processed foods we consume contain.

It is also a good time to consider a more fundamental question related to India’s food and agriculture policy: why is India addicted to sugar, and why the government is determined to push us down this unhealthy path?

Does India have a sugar problem?

Yes. In a nutshell: India produces way more sugar than it needs, using up precious water and financial resources; and as a result, Indians end up eating more sugar than is healthy. In recent years, it has been trying to use a lot of its excess sugar to produce ethanol. India blends its petrol with 10% ethanol to save a bit of the foreign exchange used for importing oil. But the use of sugarcane as fuel makes it attractive for farmers to grow more of a crop that isn’t very good for the environment, India’s agri economy, or the health of Indians.

India is the world’s largest producer of sugar. In 2022 it produced nearly 36 million tonnes. It is the second largest consumer with a domestic demand of roughly 26-27 million tonnes. An Indian on average consumes 20kg a year or about 13 spoons of sugar a day. That’s about five more than the medically recommended daily intake.

To put in perspective, Indians have better access to unhealthy sugar than fresh vegetables. Indians on average eat two portions or 250g of vegetables a day, about half the recommended quantity. The Indian government gives 1kg of sugar free to nearly 2.5 crore poorest households through the public distribution system. But the sugar industry will be quick to point out that India’s sugar consumption is much lower than the global average of 23kg, and 56kg for developed countries such as US.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there are an estimated 77 million Indians suffering from diabetes and nearly 25 million are prediabetics (at a higher risk of developing diabetes in near future). The country accounts for about 17% of the world’s diabetics.

Yet, the government and the sugar industry want Indians to consume more.

Why are Indian governments addicted to sugar?

It’s a combination of electoral concerns and the inability to reform an inefficient system.

Let’s first understand the importance of the sugarcane crop. Nearly five crore farmers depend on sugarcane and the sugar industry. A 2020 Niti Aayog Task Force Report on the sugar industry says that its annual turnover is about Rs 1 lakh crore, generating a revenue of Rs 12,000 crore for the government exchequer. “However, the sector has been facing serious issues related to profitability as well as liquidity in the last few years due to depressed sugar prices inadequately covering cane prices and mismatch between sugarcane prices and sugar prices,” it notes.

In other words, it takes more money to produce sugar in India compared to global prices. That makes Indian sugar not very competitive. In the last year or so, things have been better because international prices have gone up due to lower production in Brazil. Indian sugar is inefficient and expensive because the government provides farmers with dollops of financial incentives to grow more.

Unlike rice and wheat sugarcane does not have a minimum support price (MSP), the rate at which the government buys grains primarily from the farmers in Punjab and Haryana. Instead, the government fixes what is called the fair and remunerative price (FRP) that the sugar mills must pay farmers. The mills are mandated to buy at that price from all the local farmers in their catchment. The FRP for the 2022-23 sugar season was Rs 305 per quintal of cane.

“The returns from sugarcane cultivation are generally 60%–70% higher than most other crops. Remunerative and assured prices along with improvement in yield and recovery continue to attract farmers to growing sugarcane despite ample supply and lower prices of sugar in the market. It would not be an exaggeration to say that India has structurally become a sugar-surplus nation,” says the Niti Aayog report.

Since 2012, the FRP has increased 80%. Farmers of no other crop in India get the privilege of such steady and assured increment. Since 2009–10, the FRP has increased by about 111% (in 10 years). The net return on cultivating sugarcane is 200%–250% higher than cotton and wheat.

That’s not all. Several state governments sweeten the deal for farmers by offering bonus on top of the FRP fixed by the central government. That becomes the price at which mills must buy from farmers. For instance, in 2022-23, the Haryana government set the SAP at Rs 372, significantly more than the FRP. Farmer bodies demanded Rs 400. Punjab, UP, the largest sugar producer, and Uttarakhand followed a similar course.

With the ability to influence the electoral outcome in nearly 60 Lok Sabha seats across the country, politicians go out of their way to keep them happy.

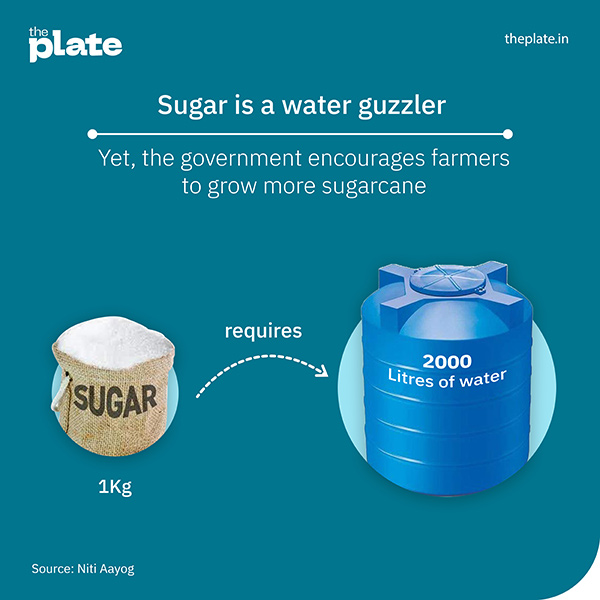

Sugarcane is not just a water guzzler requiring in excess of 2,000 litres of water per kilo of sugar compared to 300-500 litres for millets such as ragi or foxtail, but also a lazy farmer’s crop.

Like the 1990s Hero Honda tagline “fill it, shut it, forget it” that advertised the four-stroke motorbike’s fuel efficiency, sugarcane can be described as a “sow it, fill it (the land with water), forget it” crop. Sugarcane is a sturdy 10 to15-month crop that requires little attention, inputs, labour or maintenance unlike say vegetable crops.

In Maharashtra for instance, sugarcane occupies less than 6% of the total cultivated land but drinks up nearly 70% of its irrigated water.

Considering all the financial incentives, cost of producing a kilo of sugar in India goes up to Rs 35 compared to Rs 18-20 internationally. Indian sugar is currently in demand because global sugar prices are now high due to a drop in production in Brazil. But in general, Indian sugar is highly uncompetitive in the global markets. In fact, in 2019, Australia, Brazil, and Guatemala complained against India at the WTO arguing that it was dumping highly subsidised sugar in international markets. They argued that India’s sugar subsidies far exceeded WTO norms.

Isn’t it good that India is making ethanol from sugarcane that can be used as fuel?

Since India’s sugar isn’t globally competitive, and the financial incentives for farmers to grow more difficult to undo for political reasons, the question to ask is if India is trying to justify its over-production of sugar by diverting some of it to make ethanol. In 2022, India used up 3.6 million tonnes or about 10% of its sugar to make ethanol. India currently adds 10% ethanol to petrol and plans to take it up to 20% by 2030. This policy, the government claims will help India reduce its petroleum import bill proportionately.

Now, producing ethanol as a fuel from sugarcane is neither all that sustainable nor economical as it’s touted to be. A litre of ethanol at current prices costs nearly Rs 67. For ethanol blending to make commercial sense, fuel prices need to remain high. Also, promotion of ethanol doesn’t tally with the big government push for electric vehicles. As a 2022 report from the Observer Research Foundation pointed out: The gains in tailpipe emissions from ethanol blending are not only too small but also redundant given India’s goal for electrifying surface transport.

It’s high time India went for a sugar rehab.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

This is a must read article. Thank you, Vivek Sir for exploring the severe future threat of extreme sugar consumption. Your focus to the global water threat with the political monopoly of the sugarcane industry is fantastically judged.