The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

Sahyadri Farms is a unique company that is owned, managed and run by a large collective of small farmers. Its export-oriented success has made farmers prosperous. Some are even millionaires.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

A little past 3 pm, during the day’s second shift, just when the chatter of a thousand workers—mostly women, sanitised, and clad in bouffant caps and bottle green factory jackets—fully folds into the hum of machines to produce peak agro-industrial harmony at Sahyadri Farms’ massive grape packing unit, everything comes to an abrupt halt.

A visibly distressed male supervisor in a white lab coat using the PA system calls attention. There’s a lot of barking out of instructions, and some pleading involved. A worker packing freshly harvested grapes has accidentally dropped her meal coupon into one of the 500g punnets (a bread-shaped, transparent plastic box) on its way to the UK supermarket chain, Tesco.

Given Europe’s extremely high income levels and the demand for food imports because it can’t grow enough of what it needs all year round, it is the most coveted market for exporters all over the world. On the flipside, it is also the most finicky and exacting when it comes to food standards. Indian exporters feel EU strictures on the curvature of bananas, pesticide and sugar levels in other fruits and vegetables are often discriminatory.

While the error has been spotted before the box left the conveyor belt, the supervisor reminds every one of the real cost of such small acts of inattention. An entire shipment of grapes with dozens of containers (each carrying 16-20 tonnes), worth millions of dollars could get rejected, putting at risk thousands of farmers’ hard work of a whole year.

Yes, the stakes are that high at Sahyadri.

Strength in numbers

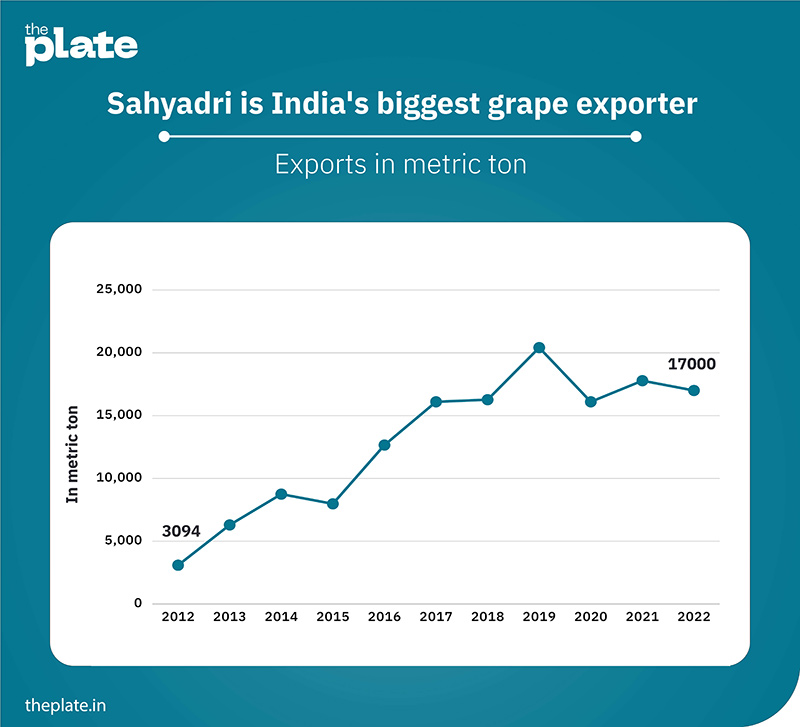

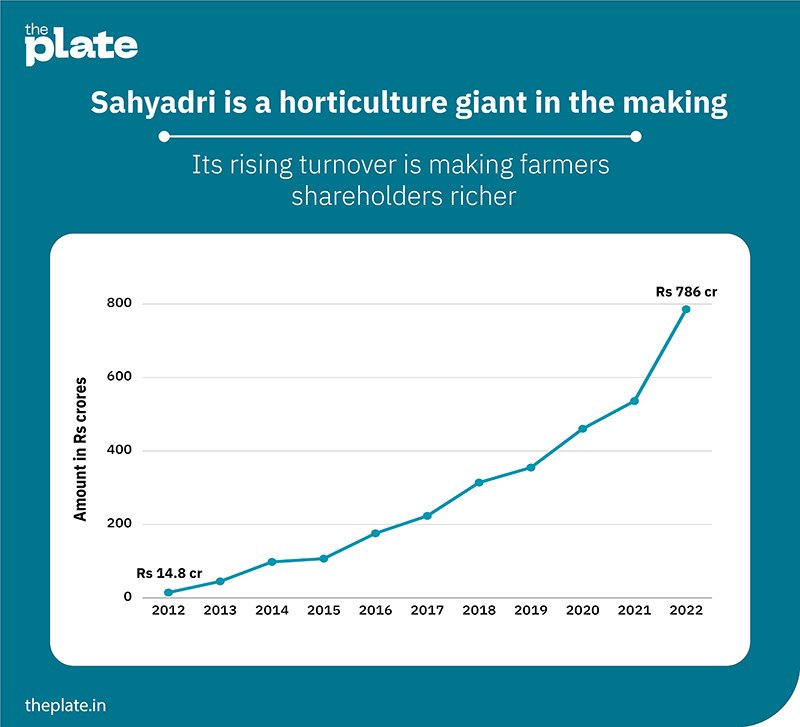

After all, Sahyadri Farms, in just 12 years of its founding, is now the country’s largest exporter of grapes. Almost 17% of the grapes that leave India’s shores are sold by Sahyadri—far more than pedigreed players such as Mahindra Agri. In 2023, its revenue crossed Rs 1000 crore. It is the largest producer and processor of tomatoes, making almost 50% of all Kissan tomato ketchup, a brand owned by global food giant Unilever.

Sahyadri Farms is a unique company that is owned, managed and run by a large collective of farmers. It belongs to a class of companies called farmer producer companies (FPC) which are a hybrid between a cooperative, such as Amul, and a private limited enterprise.

An FPC can be formed when 10 or more farmers growing the same produce, grapes in Sahyadri’s case, or say milk or turmeric, band together.

“Indian farmers have two options: collectivise or quit,” says Vilas Vishnu Shinde, the 49-year-old founder and chairman of Sahyadri Farms in a soft tone, vocal cords leathered by shouting slogans demanding a fairer deal for farmers in his youth.

Don’t mistake Shinde’s call for Soviet-style collective farming. That involved the government taking ownership of all farmland and reducing farmers to employees, who worked without a profit motive, to produce cheap and plentiful food for people in the cities.

Clad in a white linen shirt and jeans, the sharp-shaven, mustachioed, short and stocky Shinde wants Indian farmers to be rich, as rich as the IT professionals in the cities they feed.

Losses unlimited

Being a farmer in India is possibly the cruelest hand destiny can deal. Nearly 75% of Indian farmers own less than one hectare of land. That’s barely the size of a cricket field. The average monthly income of an Indian farming household—a family, not an individual farmer, mind you—according to the latest government data is Rs 10,218. That roughly translates to Rs 340 a day, at par with unskilled, daily wage that labourers in many states get under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), a scheme whose existence is testimony to India’s failure at rural uplift.

India’s agro-economy seems designed to fail Indian farmers. Small farmers buy all their inputs (pesticides, seeds, fertilisers and equipment) at retail rates and sell their output at wholesale prices. They have absolutely no bargaining power when buying or selling. Even a super-duper, bumper harvest of 10,000 kg of grapes from an acre of land, after year-round toil, at a farmgate price of Rs 30/kg means an annual income of Rs 300,000. And grapes generally offer better income than staples such as rice, wheat, onions and tomato, where according to even the most generous estimates, the farmer gets a mere Rs 30 for Rs 100 paid by the urban consumer. Greater the number of handlers from the moment a farmer loads his harvest on the truck (sorting and grading of the produce at a wholesaler’s yard; stuffing them into jute gunnies; or packing them in to smaller plastic bags with a brand sticker) to when it reaches your plate, wider the gap between the price you pay and what the farmer earns.

In theory, when individual farmers organise themselves as an FPC or a cooperative, their hand gets stronger. A collective of farmers with 500 tonnes of grapes compared to just 10 tonnes can drive a harder bargain with Ambani, Adani or even global buyers. While FPCs are a collective, they can be run as any for-profit private sector company. Unlike cooperatives, FPCs are free of government control and meddling.

“Indian farmers have to come together to benefit from the economies of scale; think of farming as a business; think of themselves as entrepreneur-managers of their farms; and compete in the global marketplace and win,” Shinde says.

Fighting the ten-headed monster

The nearly 800 grape farmers, owning small pockets of land ranging from two to five five acres in Maharashtra’s Nashik region, who joined hands a decade ago to form the Sahyadri Farmers Producer Company, are considerably prosperous. Many have farm income now in excess of Rs 1 crore, and the current value of their shares in the company could even make some millionaires.

Sahyadri today is not just India’s largest FPC, widely seen as the model to emulate for farmers across the country, but is a sort of holding company for 48 different FPCs with 18,000 farmers in its fold. When it comes to grapes, Sahyadri now has zonal FPCs bringing together grape farmers in a particular area of districts within Nashik, Sangli and Satara, or some created specific to a crop in a region – banana FPCs in neighbouring Jalgaon or citrus and cotton FPCs in Vidarbha.

The formation of about 10,000 such FPCs is a cornerstone of the government’s plans to increase farm income.

“To be a farmer in India is like fighting a ten-headed Ravana. You think you’ve solved one problem and nine crop up. We are up against countless invisible and unpredictable factors. First, there is nature. A whole year’s hard work can be washed away by unseasonal rains at harvest time; water shortage kills us. The global prices may crash or the government might change its policy overnight. There is simply no way a small farmer can win,” says Shinde.

Collectivisation isn’t a new idea in Maharashtra. The co-operative movement in sugarcane has a rich legacy in the state. In the past decades, it had bettered the lives of millions of cane farmers especially in the Marathwada region. But overtime, with government interference built into the co-operative model, the institutions were hijacked by politicians who in turn became sugar barons. “Sugar Cooperatives were given land at throwaway prices by the state to build schools and engineering colleges to benefit the children of farmers. Now, the system has become so perverted that the seats at these colleges are sold to rich students from big cities. An ordinary farmer now can’t even enter these swanky campuses,” says Radheshyam Jadhav, a Pune-based journalist and Deputy Editor at Businessline newspaper, who has tracked Maharashtra’s agro political economy for nearly three decades.

That’s the reason why Shinde says he is determined to keep political interest of any colour or persuasion completely out of Sahyadri. But, is it possible to keep politicians at bay for long?

“If you don’t seek favours from politicians, you can stand up to them and say ‘no’ to their demands. Also, we deliberately avoid dealing in crops like rice, wheat or onion that have heavy government control. Fighting the government is a waste of time and energy. In grapes for instance, the government is actually promoting exports,” he explains.

The idea of “winning” is pervasive in Sahyadri’s grape ecosystem in particular and among Nashik’s farmers in general. Sahyadri and Shinde are obsessed with winning.

But their seeds of success lay in failure.

Two men who looked west

Every vine in the world today that produces luscious grapes is a result of careful grafting. A variety called Arra is the most popular among Sahyadri farmers. But it can’t be planted directly on the fields. A small section of Arra stem (called scion, because it’s the fruit of this variety that farmers want) is wedged and taped on to another grape variant that has already laid roots and grown about half a foot tall. That’s called the root stock. The root stock is usually closer to the wild varieties. They don’t bear fruits but are tenacious. They can withstand high temperatures, droughts and even saline soil. The most coveted root stock in India is a non-fruiting variety called the Bangalore Dogridge. A vine resulting from such a marriage consummated in the nurseries can bear fruit for more than a decade.

Just as the grapevine need grafting, Sahyadri’s success needed two men of vastly different backgrounds. One was a farmer, the other a slick salesman with the gift of the gab and the ability to make a pitch tailored to fit any whim.

But they were of the same mental stock that kept this question constantly afloat in their heads: why are Indian farmers poor?

Azhar Tambuwala is a Pune-boy. At 17, his father met with a serious accident that prevented him from going back to work. With no income to pay fees, Azhar dropped out of college and took up odd-jobs, with little more than the ability to speak English fluently.

In the early 1990s, while dabbling in a variety of businesses, he wangled an order from UK to export a container of grapes. There was a small glitch: Tambuwala didn’t know where and how grapes grew, or did he have a penny in his pocket to buy them off someone who did. “I took a friend’s scooter, borrowed some money, went to Nashik and talked farmers into selling me grapes that could fill a container with the promise of better prices,” says Tambuwala, a tall, thin, bearded man in rimless glasses who is a director at Sahyadri, heading exports and marketing. Beginner’s luck, and India’s gingerly steps towards global trade, birthed a full-fledged business in subsequent years. Servicing small export orders helped Tambuwala save enough money to buy a ticket to London and meet his clients in person.

His single-minded quest in those days was: how do I connect rural India to urban markets, and thence to the world?

A few years later, in the late 1990s, when the business grew bigger, Tambuwala started taking with him an entourage of his farmer-suppliers from Nashik to Europe. These trips had a twin purpose. One, the farmers could hear directly from importers about the kind of produce and quality standards the international market expected. Otherwise, many farmers couldn’t quite fathom why Tambuwala insisted on stringent parameters for how export quality table grapes must look and taste. Rejection of batches that seemed perfectly fine to farmers could erode trust between them and Tambuwala.

Also, they could see for themselves in supermarket aisles the grapes from Chile and South Africa they were competing against.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, during field visits to farms in The Netherlands, they could see their fellow farmers get ten times the yield using modern methods and technology that seemed nothing short of magic. During the time he spent dealing with Nashik’s farmers, Tambuwala found they were extremely ambitious and always on the lookout for new ideas. If they came to know a farmer 100 km away was doing something better, they’d do their best to learn and implement it. “I wanted to break the frog-in-the-well mindset, show them the work ethic and dynamism of farmers in the West and make them realise that there was a global market waiting to be tapped. It made our farmers think, if the Dutch could do it, we could, bloody well, too!” says Tambuwala.

In 2004, on one such visit, Vilas Shinde was one of the farmers.

Mountains of debt

Vilas Shinde was born into a farming family in Adgaon, a village 15 km to the northeast of Nashik. The farm operation his joint family of six uncles ran, with about ten acres of land put together, had never turned in a profit for as long as he could remember. Shinde was a bright student. An M.Tech degree in agriculture from Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, a top agri university in Maharashtra, and the scientific techniques he learned there, failed to fix his family’s fortunes.

The immediate years of youthful agrarian idealism and a burning desire to be debt-free meant dabbling in dairy farming, growing exotic vegetables such as baby corn and broccoli, medicinal herbs, and even a resort to quackery—joining a movement championed by self-styled Gandhian Anna Hazare whose chief methods involved a return to medieval agricultural practices, and ridding rural India of the scourge of alcoholism by flogging drinkers in public.

“It’s a common refrain that farming is a gamble in India. I’ve personally experienced it is true. Only, this game of dice never ends. You keep trying your luck, again and again, crop after crop, season after season, until you accumulate so much loss that there isn’t any more room left to fall,” says Shinde. The net result of his decade-long diversions, up to the early 2000s, was debt that had ballooned from Rs 50,000 to Rs 75 lakh.

Some money was raised pawning his wife’s gold jewellery and selling small parcels of land, but not nearly enough to tackle the mountain of debt. Utterly broken, Shinde says he locked himself up inside the house for nearly five days. When family members, in the guise of getting him to run errands, forced him out to get some fresh air, he bumped into an old friend who asked Shinde if he could help load shipping containers with grapes meant for exports.

Farming is a gamble in India. Only, this game of dice never ends. You keep trying your luck, again and again, until there isn’t any more room left to fall.

Each container when full would earn him Rs 15,000. Quick mental math told him that growing grapes for exports could be good money if merely packing them into boxes provided such handsome rewards. But he had no chance of any meaningful income, forget wiping away debt, with the two acres he owned.

In 2004, he teamed up with ten other grape farmer friends who owned about as much land. This time he was betting on exporting grapes to Europe, the toughest of all markets to crack. When pooled together, their output might become sizable enough to attract an export deal. The punt paid off. A Dutch importer agreed to buy four containers of grapes from Shinde and friends. The export market fetched double, sometimes going up to four times the price grape farmers could get selling locally.

It was the new dawn; spring had come early. Shinde could see the sunlit uplands.

The valley of plenty

The current political boundaries of the Nashik district on the map of Maharashtra make it look like a pheta, the state’s traditional headgear or pagri tilted about 30 degrees to the left. The district’s geography makes it a microcosm of Maharashtra minus the beaches. It has regions ranging from the arid and dry, to mountains that receive incessant rainfall during monsoon, to extremely fertile lands with weather not too cold or dry throughout the year where it’s possible to grow pretty much any crop.

The Western Ghats or the Sahyadri range that stretches across 1600 km of India’s western coast right up to the peninsular tip at Kanyakumari in the deepest south, has its northern extremity 100 km to the north of Nashik district, in Gujarat.

In Nashik district’s Trimbakeshwar range of Western Ghats originates Godavari, the mightiest of India’s peninsular rivers that forms the country’s third largest river basin.

Just as the prodigious precipitation in Kodagu hills in the same Western Ghats in southwest Karnataka fills up a third of Kaveri’s basin, Sahyadri’s northern reaches flood Godavari sustaining three large, thirsty states of Maharashtra, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh and nearly 200 million people.

Godavari translates from Sanskrit as the giver of prosperity. The river is unlikely to keep the children at her headwaters poor. Nashik district’s per capita income of Rs 3.47 lakh, while marginally lower than Maharashtra’s Rs 3.77 lakh, is significantly higher than the national average of Rs 1.97 lakh, and most of it generated from agriculture.

A traditionally strong network of irrigation canals from the dams on Godavari and its tributaries, and farm friendly weather conditions, make the region an agri powerhouse. Nashik remains a veritable vegetable garden of the country growing onions, tomatoes, a host of beans, melons and of course grapes in abundance. Maharashtra produces almost 70% of India’s grapes with Nashik’s two lakh acres alone contributing a whopping 2 million tonnes of the national output of 3.5 million tonnes.

Grapes of love

A vineyard, when ready to harvest, beginning mid-December to March, offers possibly the most spectacular of sights in agriculture.

By late January, the undulating landscape of Nashik when viewed from a vantage is hardly a riot of colours. The tomatoes have been harvested. The fields cleared of plants bare the deep brown soil. Onions sown a couple of weeks ago have green shoots five inches high. In any case, an onion field looks drab. At the peak of peninsular India’s dry season, everything, even the shrubs are a golden straw. Vast tracts of vineyards with their thick canopy, and winter wheat whose silky, shampooed hair-like strands that will turn from green to blonde in a month, offer the only green relief in a sea of brown monochrome.

When you enter a vineyard, head bent and the body a bit crouched, everything feels a few degrees cooler. The grape leaves are broad enough to hold a standard south Indian restaurant-style set of two-idlis-and-generous-chutney. Sunlight filtering through a thick layer of the craggy-outlined grape leaves creates playful shadows.

It is the perfect setting for the most erotic of Biblical poems called the ‘Song of Songs’, an epithet signifying the greatest importance. It can be read as King Solomon’s expression of love for a beloved wife that is intense, untainted by selfishness and sin, or as an allegory for Christ’s love for his followers and vice versa.

It goes:

Let us get up early to the vineyards;

let us see if the vine flourish,

whether the tender grape appear,

and the pomegranates bud forth: there I will I give thee my love

The Biblical song inspired one of India’s best romantic movies. The legendary Malayalam director Padmarajan made a film in 1986 called ‘Namukku Parkkan Munthirithoppukal’ (A vineyard for us to dwell in) starring Mohanlal, a Syrian Christian grape farmer, appropriately named Solomon who wins the hand of a woman named Sofia (not Sheeba, lest it gave the game away entirely!). It also features the most romantic of all vineyard songs ever filmed in India. That is of course this writer’s opinion, but we digress.

Today, as more Nashik grape farmers have tasted the fruits of success in the export market, the fields in the run up to harvest wear an odd look. The sun-facing periphery of vineyards are covered by a string of old sarees and thin bedsheets. The grape bunches are wrapped up in old newspapers.

Growing table grapes for exports, while more profitable, is quite demanding compared to wine grapes. Being on the right side of pesticide residue limits aside, the berries must look beautiful. They can’t be too big or small. The emphasis on the uniformity and consistency of size and shape and colour of each harvested bunch is such that you wonder if western consumers want produce shaped and nourished by nature, or fruits injection moulded in a factory. Excessive sunlight creates two problems. It ripens the grapes in a bunch inconsistently, and hastens the build-up of sugar. The level of sweetness Indians expect in grapes just wouldn’t cut it in Europe. The Brix scale is a measure of dissolved sugar content in any solution. It is used to measure the sweetness of fruits such as grapes. The Brix content for grapes to Europe must range from 16 to 20 degrees, whereas the Indian palate prefers sugar content 24 degrees or higher.

A change of fortunes

In the spring of 2004, when Shinde and friends shipped the first of their export order of four containers of grapes to The Netherlands, Shinde’s hopes of a bright future knew no bounds. Despite some initial glitches, the business thrived. By 2010, the group had expanded to 25 friends, and with the help of Tambuwala’s sales acumen, they were exporting 160 containers of grapes.

A major crisis struck just then. The European Union put in place stringent restrictions on the residue of a plant growth hormone controller called Lihocine (ironically, a brand sold by German chemical giant BASF). The grapes Shinde sent to the continent were rejected outright. Markets crashed all over. A box fetching 10 euros had to be offloaded at 10 cents.

“The use of Lihocin was an accepted practice across the world. Nobody, the importers or the Indian government informed us about the new residue levels of Lihocin because we were too insignificant. Forget my personal debt, I had now pulled in all my friends who believed in me, into an even bigger hole. There couldn’t be a crop for next season’s exports. There would be no money to even pay farm labour. The banks told us the only option we had was to sell our land and pay all the loans. We didn’t have the courage to tell our families what had happened. I was back to square one,” recalls Shinde.

Call it irrational exuberance, or the last throw of dice. Vilas Shinde sold all his land from the profits he had made six years past to recompense everyone’s loss.

Such leadership in adversity proved to be the perfect sales pitch in attracting more grape farmers.

“I can’t forget the sacrifices Vilas anna made to get people like me prosperous,” says Govind Uphade, a 38-year-old grape farmer in the Dindori taluk of Nashik district. But there is no time to get too sentimental. Harvesting scissors in hand, Uphade, a slender man wearing a white shirt stained by grape sap, sleeves buttoned down, and black polyester trousers, mentions almost matter-of-factly that his annual family income is Rs 1.25 crore from a holding of 40 acres compared to the two acres he owned before joining hands with Shinde in 2010.

Extensive use of technology helps to maintain the quality that would fetch farmers the best price. For instance, with digitalised farms, every box of grapes can be traced right down to the vineyard. Sensors and IoT devices at the vineyards capture key data that is supplied to the farmers in the form of a simple dashboard on Sahyadri’s mobile app. “Our team of agronomists too can monitor if individual farmers are following the right processes. We can see real time soil, moisture content, whether the plants need watering, analyse changes in leaf colour to predict the onset of a disease or pest attack and recommend preventive care,” says Sacheen Walunj, CEO, Sahyadri FPC.

“We had seen the benefits of coming together and competing in the global marketplace. Relying on the government for help is futile, farmers must look after their own interest. They have to find solutions for their problems by getting together. To export grapes, you need to have a cold chain. Post packaging, they need to be pre-cooled at zero degree Celsius for a shelf life of 60 days. How can an individual farmer with two acres do it,” says Shinde over a special Republic Day breakfast of pav bhaji and jalebis at the Sahyadri canteen.

A fruity Amul?

It would be unfair to speak of Amul, a Rs 61,000 crore farmers’ cooperative and global dairy giant in the same breath as the Rs 1000 crore Sahyadri.

But listening to Shinde, Tambuwala and Sahyadri members on why farmers need to think as entrepreneurs, use professional management approaches, and look at the market as an opportunity rather than a threat, it would appear they are singing from the scoresheet of Varghese Kurien, the founder of Amul and chief architect of India’s White Revolution. In his 2005 autobiography, I Too Had a Dream, he wrote: “Today India is among the most industrialised nations in the world. How did this happen? It happened because we combined our native shrewdness and the money our great industrialists had with professional management. I was convinced that the biggest power in India is the power of its people – the power of millions of farmers and their families. What if we mobilised them, if we combined this farmer power with professional management? What could they not achieve? What could India not become?”

I was convinced that the biggest power in India is the power of its people – the power of millions of farmers and their families. What if we mobilised them, if we combined this farmer power with professional management? What could they not achieve? What could India not become?

Varghese Kurien, the founder of Amul and chief architect of India’s White Revolution In his 2005 autobiography, I Too Had a Dream

Mark Kahn, managing partner at Omnivore, a venture capital firm focussed on investing in the country’s agri sector, too, sees parallels between Amul and Sahyadri.

“Sahyadri’s success is analogous to the White revolution and Amul. Back then, two factors were at play: one, a strong leader like Varghese Kurien comes along and changes everything. The second is institutional. Dairy farmers had an inherent need to co-operate with a perishable product that loses all value in two days. A farmer with two animals can’t afford milk chilling or processing infrastructure. Similarly in Nashik, the impact Vilas Shinde has had as a farmer leader is phenomenal. And if you put together a thousand grape farmers, who are individually profitable, they could afford refrigeration, cold chains and other infrastructure to target the global market,” says Kahn, a tall slender American with thick-rimmed glasses, who is more gung-ho about Indian farming than most Indians.

In 2011, Sahyadri began operations as a full-fledged FPC and by 2016 had the means to set up a 110-acre factory-cum-headquarters where it can process not just 300 tonnes of grapes a day but 1,200 tonnes of tomatoes. While grapes are seasonal, the nonstop, year-round processing of tomatoes keeps the impressive campus with its red brick office buildings, giant white-roofed warehouses and manicured lawns soaked in a smell of ketchupy sourness.

The impact Vilas Shinde has had as a farmer leader is phenomenal. If you put together a thousand grape farmers, who are individually profitable, they could afford the infrastructure to target global markets.

Besides grapes and onions, Nashik is one of India’s biggest tomato producing regions. Among India’s chief vegetables, tomato prices are prone to the wildest price fluctuations. While prices skyrocket between May and September because of extreme summer heat and monsoon disruptions, there is often such a glut of supply in winter and spring that prices crash to almost Rs 2 a kilo at the farmgate. At that price, it doesn’t even make sense to harvest the tomatoes. That is when the images of farmers dumping tomatoes by the tractorloads in protest make headlines.

Tomatoes are in demand all through the year. There’s no reason it should have the billing of ‘the tragic crop’ among farmers. “We can easily solve the problem of seasonal excess through processing of tomatoes. Whenever the price drops below Rs 5/kg we start buying in big quantities from the farmers so that they can at least recover their cost,” says Shinde. Sahyadri is now the biggest contract manufacturer of Kissan ketchups and fruit squashes.

Sahyadri has become the first farmer owned company in India to attract foreign investment. In September 2022, it raised Rs 310 crore from a clutch of European investors. What makes Sahyadri the most successful FPC? “You need a crop specific, integrated value chain approach where the farmer is in control of all things from the farm to the market. And that value chain should be globally competitive,” says Shinde.

With foreign investment comes criticism from some farmers outside of its network that Sahyadri is now run like any other corporate firm. Shinde even has ambitions of listing the company on the stock markets in the next five years. Keeping investors happy might take precedence over the betterment of farmers?

“That’s nonsense,” says Kahn. “They’ve carved out the food processing part of the business and used it to raise money. But it is still owned by the FPC and the farmers. Look, everyone says, oh, an FPC needs investment to attract talent. For that you need money. Sahyadri has done just that. It needs to be celebrated rather than say it compromises the spirit of an FPC.”

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

Just brilliant! This is journalism.

Thank you Kalyan.

Superb . An eye opener for all the FPOs who have ideas but not able to get going.

Thanks Mr Dash

Remarkable!!

Sahyadri as well as The Plate.

Need more stories like these happening in India.

How can I place order for a box of black and a box of green best sweet grapes for self use. Rate and courier charge ‘s please.

Address Mumbai 400053

This is a master class. Too much to read and digest. It has Sahyadri, Leadership, FPC, exports, Sahyadri v. Amul. I would do it in #multiple pieces. Thank you! Keep the good work flowing!

Thank you, Nimish! Keep following us