The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

In Odisha, scientists are biofortifying rice to fight malnutrition without changing what people eat. If it scales, the model could transform public health across the Global South.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

In mid-November, as the monsoon has fully retreated, Odisha’s dry season begins, stretching nearly six months until the onset of the southwest monsoon. On the 70-kilometre drive from Titlagarh, where summer temperatures can cross 50 degrees Celsius, to Bolangir, the terrain is a mix of gently rolling plains, undulations and isolated hills; there are barely any potholes. The riverbeds lie dry, overrun by vast stretches of kans grass. In full bloom, its flowers resemble white ostrich feathers swaying in loose unison.

And yet, the canals that criss-cross the region continue to course with water. Village ponds brim and sparkle with waterlilies. The land itself glows with the green of vegetable patches and the gold of a bumper rice crop ready for harvest. For those of us old enough to remember the headlines of the late 1990s, this scene is nothing short of a miracle. This is the infamous KBK region—abbreviation for Koraput-Bolangir-Kalahandi—three districts stacked like Jenga blocks in western Odisha, with Bolangir in the north and Koraput at the bottom bordering Andhra Pradesh.

Just two decades ago KBK was shorthand for darkness and deprivation. With nearly 90% of the population living below the poverty line, the region drew international attention for chronic hunger, migration, and some of India’s worst human development indicators. It was the symbol of India’s failure.

But things have changed dramatically. New roads slice through areas that were once inaccessible. Massive irrigation schemes have turned this former dustbowl into a rice bowl.

Since 2004, rice production in KBK has more than doubled to 1.7 million tons a year–more than 10% of Odisha’s overall impressive leap to 12 million tons. Other crops such as vegetables and pulses have prospered too. Hunger, in the caloric sense, is no longer the primary challenge here. The battle against empty stomachs may have been won, but the war for nutrition isn’t.

It’s not just the story of KBK but India at large. Despite becoming the top rice producer in the world and running the largest free and subsidized food programme in the world that covers 800 million people, India’s health and nutrition statistics make for sorry reading. The most recent National Family Health Survey shows that more than a third of Indian children under five are stunted. Nearly one in five are ‘wasted’ (acute malnutrition where a child is too thin for their height– a sign of failure to gain weight adequately). Anaemia affects women and children at alarming levels and is now visible among a quarter of adult men. Alongside this undernutrition sits a growing burden of non-communicable diseases. Over 15% Indian men and 13% women have high blood sugar or are on diabetes medication.

“This coexistence of undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, and rising non-communicable diseases reflects a triple burden. Much of this is linked to low dietary diversity and heavy reliance on refined staples, especially rice based diets,” says Swati Nayak, the South Asia Lead for seed systems at the International Rice Research Institute and the winner of the 2023 Norman Borlaug Field Award given to young scientists for outstanding contributions in food and nutrition security.

Rice is the single most important food crop in the world. It is the staple food for half the world’s population—from Jamaica to Japan and the Middle East to Malaysia. In India, the socio-economic and cultural importance of rice cannot be overstated. India has recently become the world’s largest producer of rice at 150 million tons overtaking China, and it accounts for nearly half of the world’s rice trade. Major festivals such as Sankranti are linked to harvest. Replacing it on our plates is simply unthinkable.

But a modern life that involves less physical labor has turned our beloved grain into a chief culprit for lifestyle diseases.

A rice dominant-diet can cause rapid spikes in blood sugar, which increases the risk of diabetes and weight gain. It also fills the stomach without providing enough essential protein or vitamins, leaving you well-fed calorically but starving nutritionally.

In a state like Odisha, still among the poorest in the country, where access to vegetables and protein remains a challenge, a completely rice-reliant diet poses serious public health risks.

So policymakers and scientists in Odisha are asking a different question. Instead of changing diets, can the staple itself be made healthier?

The Odisha government has partnered with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) to launch what it calls the world’s first Speciality Rice Programme.

The premise is pretty straightforward. Improve the nutritional quality of rice itself, without altering how people cook or eat it.

The programme focuses on scaling new rice varieties developed by scientists that are naturally biofortified. These include rice that is higher in protein, richer in micronutrients such as zinc, or lower in glycaemic index. Crucially, these varieties are designed to look, cook, and taste like the rice people already eat.

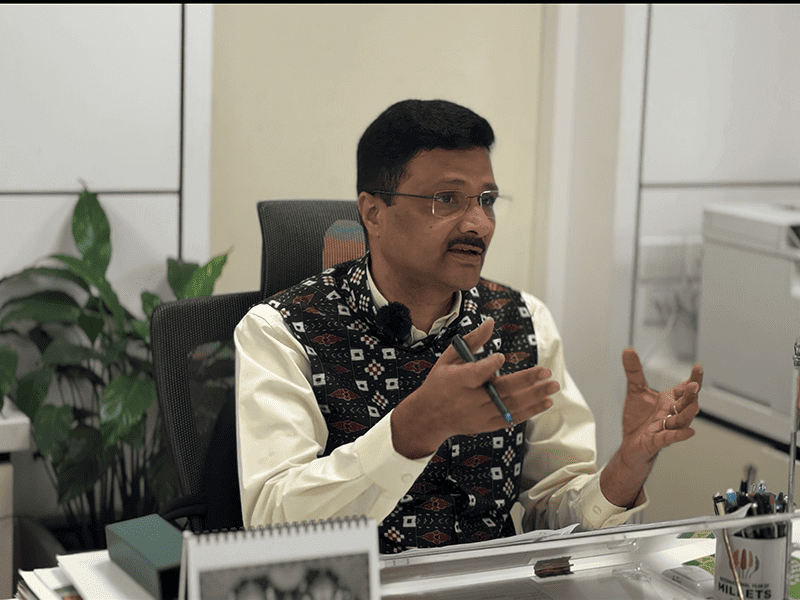

“The speciality rice programme focuses on deploying or mainstreaming and scaling the healthier rice varieties to enhance consumer nutrition as well as farmers’ income. As a pilot, we have chosen four districts where malnutrition is a big problem,” says Arabinda Padhee, Secretary, Agriculture and Farmers Empowerment, Odisha and one of the most powerful bureaucrats in the state. Perhaps, being the chief administrator of the Jagannath Temple in Puri provides a more accurate measure of his power in a state where the standard greeting from cities to villages is ‘Jai Jagannath’.

Padhee himself has a PhD in agri sciences and is a proud ambassador of Odia culture, always attired in colourful Sambalpuri ikat jackets. Krushi Bhawan, the agri department’s HQ where Padhee works out of, is one of the most striking buildings in Bhubaneshwar. Built in 2020, the four-story building is designed around a lush central courtyard with ponds and trees. Its standout feature is the intricate brick façade patterned like traditional Sambalpuri ikat handloom textiles with geometric motifs in earthy tones. It’s meant to make citizens feel welcome rather than to intimidate (if they can get past the cordons of security, that is).

Under the Speciality Rice Project in its third year, the Odisha government has managed to convert some 15,000 farmers to start growing the new biofortified varieties of rice on 15,000 hectares.

“The programme’s role includes varietal research and breeding, nutritional profiling, agronomic testing, and connecting academic discoveries with farmers and markets. The goal is to ensure that these innovations reach the fields and the plates and kitchens of consumers. Through a global network and local partnerships, the programme aims to be scalable, sustainable, and aligned with both health and livelihood goals,” explains IRRI’s Nayak.

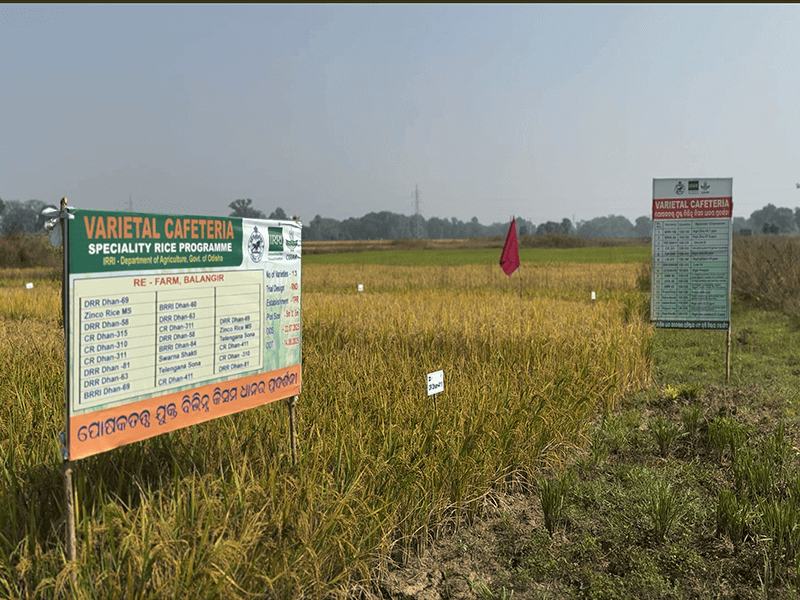

To begin with, scientists at IRRI in collaboration with government research organizations such as the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) develop and test the new varieties. Once approved, the Odisha government and IRRI create ‘rice cafeterias’. The cafeterias are simply vast demonstration fields of the 20-odd new biofortified varieties they’ve chosen to popularize. The farmers can visit the cafeterias to evaluate them first hand on a host of parameters such as yield potential, disease resistance, tolerance to adverse climate and grain quality. When farmers choose a certain variety, the state government provides them with seeds for free. IRRI also conducts monthly village camps to evangelize the new varieties with cooking and tasting quality demonstrations of the biofortified varieties followed by a communal feast for the farmers.

But it is in the labs that heavy lifting happens. Biofortification is often misunderstood as genetic modification. It is not. In a sense, humans have been genetically modifying plants and animals to make them yield more or better through techniques like grafting and selective breeding since agriculture began. Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) today involves altering the genes of a plant in a lab. For instance, genetically modified ‘Golden Rice’ was created by adding to the rice genome a gene from the daffodil plant–an unrelated species–to increase beta-carotene levels 20-fold in rice.

“Biofortification means genetically improving food crops like rice for nutritional traits like higher zinc, iron or protein. With polished and milled rice we eat, micronutrients are lost. Biofortification helps to retain the nutrients,” says Krishnendu Chattopadhyay, principal scientist, Central Rice Research Institute (CRRI), Cuttack.

CRRI is one of the oldest and top rice breeding centres in India that began work on biofortification of rice in 2009. Clad in a yellow short-sleeve shirt, jeans and white sneakers, with professorial black-framed glasses, Chattopadhyay, 56, scarcely looks the man who was instrumental in creating one of the world’s first biofortified rice varieties. He speaks in soft, measured tones—the voice of a scientist who has spent decades perfecting CRR Dhan 310, a rice variety with a protein content of 10-11% compared to the usual 6%.

To create new biofortified varieties breeders like Chattopadhyay first identify rice that could be a wild race or one that is little known but with the desired nutrients like protein or zinc. It is like picking up a book from a library of crops where each one is preserved and its traits catalogued. Bigger the library, greater the chances of success. International research organisations like IRRI have the ability to create mega libraries with access to seeds from across the world.

In the case of CRR 310, Chattopadhyay and his team found a variety called ARC 10075 from Assam with high protein content but very low yielding. They then crossed it with popular high-yielding varieties like Naveen and Swarna. Scientists then spend 7-10 years selecting offspring plants that combine both traits while testing them across multiple growing seasons and locations. The most promising candidates underwent rigorous field trials and nutritional analysis before being released to farmers. The entire process requires patience and precision to ensure the new variety was both nutritious and viable for farmers to grow at scale.

Currently the subsidized rice supplied by the government through ration shops is externally fortified. Vitamins and minerals like iron, B12 and folic acid are mixed with rice flour and kernels that look like rice are created. One kilogram of these kernels is added to 100 kg of rice. This method has some problems, it is expensive and the bioavailability of minerals to the human body can be low. Plus it is found that many consumers pick out the fortified kernels that look slightly different from rice, thinking it is contamination. External fortification treats food like a delivery vehicle for pills. Biofortification turns the farm itself into the first line of public health protection—at low-cost, and at scale.

But scaling innovation is often harder than creating it. In Odisha, adoption depends on reliable seed supply, farmer confidence, and market demand.

The new rice varieties are already a big hit among farmers.

Jogeswar Sa, 49, is a short but sturdy farmer with a lush head of black hair, dressed in a black and canary yellow dhoti and matching shirt with large Sambalpuri patterns. He was impressed by a zinc-rich speciality rice variety called BRRI 69 at one of the demonstration plots. The panicle–the branching cluster at the top where rice grains hang like an upside-down Christmas tree–was longer, indicating higher yield, and the grain itself heavier. He switched to the new rice on his two-acre farm. “I get 5-6 quintals per acre more. The rice itself is perfect for pakhala bhat [cooked rice soaked overnight for light fermentation; hugely popular in Odisha] and fish and mutton curry,” beams Sa.

The demand among farmers is such that seeds are at a premium. Since these are new varieties, neither the research organisations nor government institutions such as the state seed corporation have the stock to keep pace.

IRRI and the Odisha government encourage farmers who are part of the programme to make seeds from a small part of their output. Seed production is specialized. An acre of rice needs 15-20 kg of seeds. Farmers need to select plants in a vast field that produce the most and healthiest grains; harvest and thresh them separately; store and process them with care so that they have the best chance of yielding in the next season.

“We have adopted a seed-to-market value chain approach in this entire project. Crucially, we are involving women farmers and self-help groups wherever possible. We want them to become the champions in every part of the project from raising the crop, aggregating the produce, seed production and marketing,” adds Padhee.

Binapani Mangal, 36, is a two-acre farmer in a village called Akhuapada on the shores of Baitarni, a large flood-prone river in Bhadrak district, 100km to the north east of Bhubaneshwar. The landscape in the coastal plains only gets a denser green and the tree canopies are broader than in Bolangir. Mangal is a woman with strong, broad shoulders and high cheek bones who zips around in a scooter. She has been growing a speciality rice variety called BRRI 84 for two years on half her holding. It is a zinc-rich variety with long slender grains and a red tint. Since red rice is common in these parts, the BRRI 84 fits easily into the diet. “Since the rice boosts immunity power, we are not only able to sell it for a higher price but also get five quintals more per acre,” she says.

Despite the growing irrigation network, more than 40% of farmers in the Bolangir region depend on rainfall. The region is also susceptible to drought. Another key reason for the popularity of speciality rice varieties is their hardiness. “While our farmers are increasing seed production every season, the demand is such that we run out of stock in no time,” says Motilal Misra, chairman of the Puintala Farmer Producer Company (FPC) in Bolangir district. A farmer producer company or FPC is a social enterprise that’s a hybrid between a cooperative, such as Amul, and a private limited company. An FPC can be formed when ten or more farmers in a region band together. But it has to be owned and managed by its member-farmers. Many members of the PFC are women who make value-added products such as poha, rice flour and crackers under its own brand. “If regular poha sells for Rs 50/kg, ours costs more than double. But we can’t match the demand for sugar-free rice products,” adds Misra.

Odisha’s speciality rice initiative offers a different model for addressing malnutrition. It does not rely on supplements, behavioural change campaigns, or imported health foods.

Instead, it works at the level of the seed. For populations that eat rice every day, this approach offers better nutrition without disruption. For farmers, it provides higher incomes and resilience. For policymakers across the Global South, it presents a replicable model that works within existing food systems.

It is not a dramatic transformation of diets. It is a subtle shift in what grows in the field. And for a country where rice remains central to life, that may be the most practical place to begin.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.