The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

India’s wild tomato or onion price fluctuations make farmers and consumers cry every year. Solutions needn’t involve rocket science.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

Two rather different sets of rocketry-related headlines have caught India’s attention in recent weeks: India’s second attempt at a moon landing through Chandrayaan 3, and the skyrocketing prices of tomatoes.

It begs the rhetorical question, on the lines often posed by the Western media much to the irritation of Indians: despite accounting for the country’s vastness and the diversity of its challenges, how does India manage to send a two-tonne payload to the moon across 3.85 lakh km while struggling to reliably supply tomatoes from Dewas to Darbhanga, merely 1300 km apart?

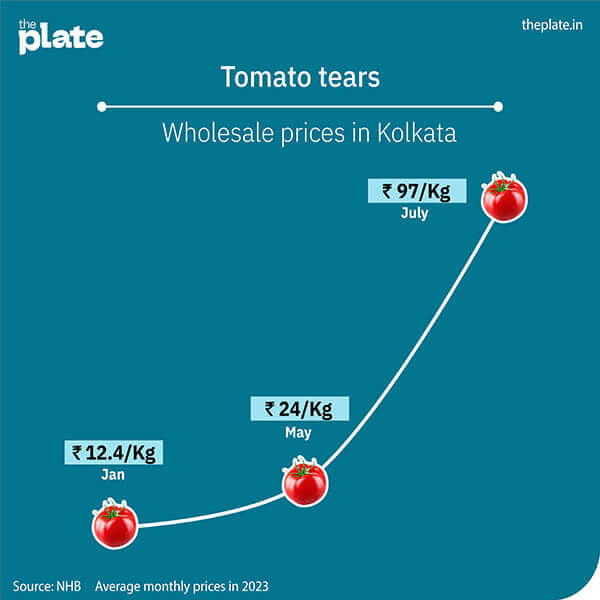

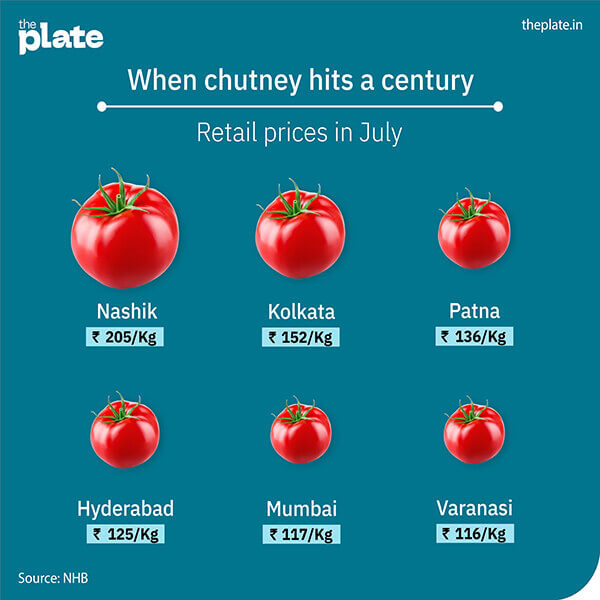

In June and July 2023, the retail price of tomatoes in India rose astronomically above Rs 100/kg. According to the National Horticulture Board’s data, consumers in cities such as Kolkata and Patna need to shell out as much as Rs 150-200. Tomato slices aren’t to be seen in sandwiches and burgers served up by even the big quick service food chains. Your order of pasta arrabbiata is likely to turn the restaurant owner’s face redder than the sauce.

In contrast, just a few months ago in April, angry farmers were dumping tomatoes on the road in protest as their selling price dropped as low as Rs 1-2/kg. It was a repeat of the onion farmers’ plight in February and March.

Feast or famine

India is the world’s second largest producer of fruits and vegetables, including tomatoes. Its output of staple vegetables such as tomato, onion and potatoes (TOP) is significantly higher than domestic demand. Yet, why is India’s fresh food market in a permanent feast-or-famine mode?

Unwilling to miss out on a PR opportunity during a crisis, the Ministry of Consumer affairs on June 30, 2023 launched the ‘Tomato Grand Challenge’ inviting students, research scholars, and the industry to a “hackathon to generate innovative ideas to enhance tomato value chain and ensure its availability at affordable prices”.

Even if the government had no time to read the reports and suggestions of the countless experts it commissioned, it could have called up someone like Vilas Shinde, the chairman of Sahyadri Farms, a Rs 1000 crore farmer producer company (FPC) and one of the largest tomato buyers in the country.

An FPC is like any other company, but wholly owned and operated by farmers in a particular region.

Sahyadri processes 1200 tonnes of tomato a day and manufactures 50% of Kissan ketchup, a brand owned by the global FMCG giant Unilever.

India produces nearly 22 million tonnes of tomatoes and consumes about 20 million tonnes. With paltry exports, there should be no price shock.

“The simple reason for high tomato prices is supply-and-demand principles of economics. In April when the prices went to Rs 1-2/kg, farmers had no motivation to pay attention to their crop. They were not even getting 30% of their production cost as income. They will obviously uproot their tomato plants and try to grow something else. Every agricultural commodity glut in India will be followed by a massive shortage. It’s a vicious cycle for both farmers and consumers,” says Shinde.

Sweet and sour

But it needn’t be so. India is one of the few countries in the world that can grow tomatoes all-year.

India’s tomato production peak occurs between October and April. “The best time for tomatoes pan-India is post February. A day time temperature of 25-32 degrees Celsius is ideal. When heat crosses 38 degrees, the fruit-setting doesn’t happen,” explains AT Sadashiva, a former principal scientist at Indian Institute of Horticulture Sciences (IIHR), Bengaluru, and renowned tomato breeder who has developed several varieties of tomatoes that yield more than 40 tonnes per season in his 30-year-stint as a public sector scientist. Creating a commercially viable new plant variety can take as much as a decade.

Tomato in India is a four-month crop that starts yielding after 60 days of sowing.

“When prices started to crash in March, most farmers made massive losses with their first harvest and didn’t pay any attention to the next two months of yield. There was no point spending on water, pesticides or even harvesting the crop. Our income was barely Rs 1 lakh per crop compared to the usual Rs 2.5-3 lakh. Many didn’t bother sowing the monsoon season tomatoes. They switched to bitter gourd or bottle gourd,” says Ganesh Kadam, a two-acre tomato farmer in Nashik.

During the summer months of May and June, supplies from Narayangaon in Maharastra’s Pune district and Kolar region in the Andhra-Karnataka border form the country’s tomato lifeline.“This year there was the cucumber mosaic virus, and untimely rains that damaged the tomato crop in Kolar,” adds Sadahiva .Excessive heat, rainfall or pest attacks do have local impact on output, but to blame nature alone and explain away a recurring crisis would be a cop out.

No secret sauce

“We have failed to create a milk-like ecosystem for vegetables. Milk goes bad in four hours, tomatoes can last four to five days. But there is no way to store or process tomatoes in or near our mandis. The only solution is the creation of an integrated value chain where farmers grow to demand and convert the surplus into processed products. Farmers have to control this value chain,” says Sahyadri’s Shinde.

India’s tomato productivity at 10 tonnes per acre is considerably below even the global average of 35 tonnes. The country’s much vaunted ‘Kisan Rail’ scheme that hoped to connect producers and consumers through subsidised freight rates and dedicated carriages barely functions.

The first step towards an integrated approach, according to Shinde, must begin with helping farmers achieve yields of 40 tonnes/acre. That would automatically bring the cost of production down.

“The government has to incentivise the private sector to set up tomato processing plants. At Sahyadri, we buy tomatoes for processing when there is a glut. When we start buying in large volumes, the prices stabilise. Even partial-processing of fresh food can extend its life by six months. Tomatoes can be processed to last a couple of years. When farmers are assured of stable prices, they can focus on producing crops that are profitable for them and healthy for consumers,” says Shinde.

India’s tomato processing infrastructure is so poor that it is considerably cheaper to import tomato paste of a better quality from China. Also, a myopic focus on the domestic fresh tomato market comes at the cost of popularising processing-grade tomato varieties among farmers that would fetch them better prices. Such tomatoes need to be sweeter and have lower acidity and water content.

The work of India’s scientists such as Sadashiva and farmer entrepreneurs like Shinde would continue to go to waste until there is a policy that matches their will.

“Tomato prices will come down in November. Consumers will be happy. Farmers will dump their produce on the road, yet again. Uske baad kya [what thereafter]” asks Shinde.

There will be yet another cycle of farmer protest and consumer distress. You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to predict that.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.