The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

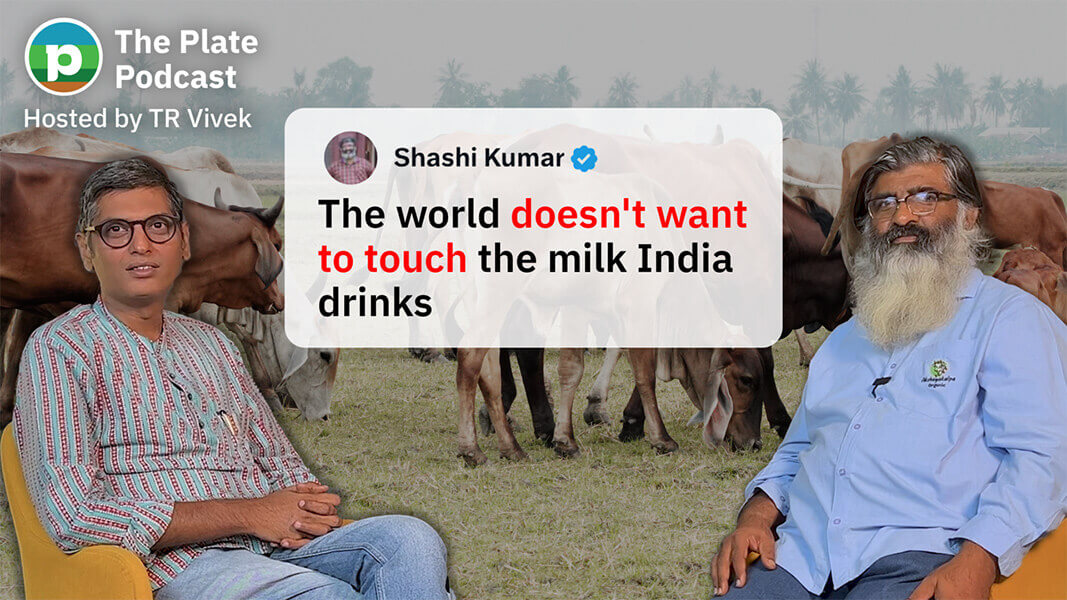

India’s dairy sector, once a shining example of agricultural success, is facing a crisis. Declining growth rates, low farmer incomes, and quality concerns threaten to undermine the White Revolution.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

The dairy industry has long been a pillar of Indian agriculture, earning its status as a standout success story. From the days of milk shortages at independence to becoming the world’s largest producer of milk, India owes much of this transformation to the White Revolution led by Verghese Kurien. However, as India celebrates 50 years of this achievement, the sector faces a raft of challenges that could reverse its hard-earned gains.

A legacy of success

At independence in 1947, India’s dairy sector was unorganized, with low productivity and insufficient supply. Most milk came from buffaloes, as indigenous cows were primarily used for draught purposes. By the 1970s, the White Revolution, spearheaded by the establishment of Amul and the National Dairy Development Board, ushered in a paradigm shift. Cooperative models linked millions of farmers to chilling centres and urban markets, ensuring consistent supply despite milk’s perishability. Today, milk availability has soared to approximately 420 grams per person per day, a stark contrast to the deficit years. Yet, the industry’s productivity remains well below global standards. Indian cattle yield an average of 3–4 litres of milk daily, compared to the 20 litres or more achieved by European breeds.

The slowdown in growth

Recent data underscores a worrying trend: milk production growth has halved from 6% annually to just 3.78%. Experts attribute this decline to a combination of outdated breeding programs, poor farm management, inadequate farmer education, and over-reliance on subsidies. Shashi Kumar, founder and CEO of Akshayakalpa Organic, highlights systemic issues. “We have doubled our cattle population since 1950 which has contributed to the increase in production. Most farmers lack access to modern breeding or feeding practices, perpetuating inefficiencies.”

The cost of cheap milk

India’s cooperatives, like Amul and Nandini, have been instrumental in making milk affordable. However, low consumer prices come at a cost. Farmers often sell milk at or below the cost of production.

In Karnataka, the cooperatives pay farmers ₹35 a litre that includes a ₹5 incentive the government pays from taxpayer money. Shashi Kumar explains, “Most dairy farming is sustained by unpaid family labor and unaccounted costs. It is impossible to produce a litre of milk below ₹35. So in effect, no dairy farmer makes any money.”

Artificially low prices also hinder private sector growth and innovation. Companies like Hatsun, one of the largest publicly traded dairy companies, and Akshayakalpa, which operate outside the cooperative system, invest heavily in quality and farmer education but struggle to compete with subsidized rates.

Despite this, demand for premium, organic milk is growing, with Akshayakalpa’s products commanding prices up to two-to-three times the market average.

Global quality concerns

India’s milk quality issues extend beyond domestic markets. Indian dairy products consistently fail to meet global phytosanitary standards, limiting export opportunities. Poor animal nutrition, unhygienic milking practices, and inadequate cold chain infrastructure contribute to substandard milk quality. “We may be the largest producer, but not many countries want to even touch our products,” says Shashi Kumar. The Way Forward

To prevent a potential crisis, Shashi Kumar stresses the need for systemic reforms:

1. Modernizing Breeding Programs: Current breeding strategies, including crossbreeding indigenous cows with exotic breeds, must be better managed. Investment in indigenous breed improvement, as seen in Brazil’s success with Indian-origin cattle, is crucial.

2. Farmer Education and Support: Comprehensive extension programs can teach farmers sustainable feeding, breeding, and farm management practices. For instance, Akshayakalpa employs one extension officer for every four farmers to ensure adherence to quality protocols.

3. Fair Pricing and Reduced Subsidy Dependence: Establishing a fair price mechanism for milk that reflects actual production costs will empower farmers and attract private investment.

4. Focus on Quality: The industry must prioritize antibiotic-free, toxin-free milk production to tap into premium markets and improve domestic health outcomes.

5. Infrastructure Development: Expanding cold storage and chilling infrastructure will reduce post-production losses and improve milk quality. India’s dairy sector stands at a crossroads. The lessons of the White Revolution prove that with the right vision and commitment, transformative change is possible. However, the path forward requires embracing quality, sustainability, and farmer empowerment. Without these measures, India risks squandering one of its most remarkable agricultural achievements. The stakes are high—not just for farmers, but for millions of consumers and the nation’s food security.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.