The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.

The government starts to panic when there is a slight increase onion prices, egged on by sensationalist media that plays up the “plight of housewives”.

TR Vivek

TR Vivek

Onion is India’s most politically sensitive crop. Any increase in its retail price is a nightmare for politicians. Why is that so? India, an onion surplus nation, cannot make money in exports even when there is a global shortage. The Plate’s TR Vivek spoke to Nanasaheb Patil who perhaps knows more about onions than anyone else. He is an onion farmer himself and a member of the Agriculture Produce Marketing Committee or APMC at what is known as Asia’s biggest onion market at Lasalgaon in Maharashtra’s Nashik district.

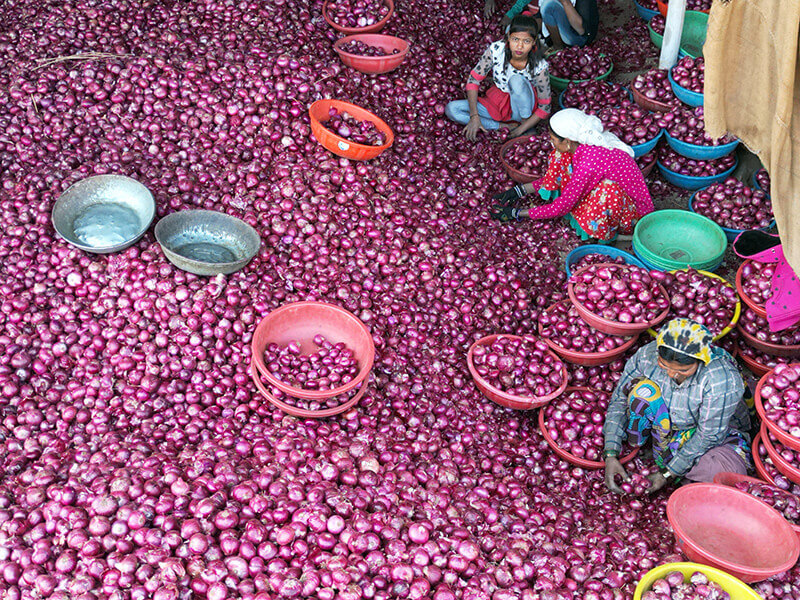

Onion is a commodity that is part of India’s daily diet. The first crop of fresh onions arrive in August from Karnataka, starting from Bangalore and Hubli. The supply then shifts gradually north: Kolhapur in September, Nashik by October. This lasts till January or February end. The August-to-February cycle brings red onions that are more perishable. They have shelf life of 2-3 weeks. From late February and early March, the pink onions from Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan start coming in. Fresh arrival lasts until April end. After April, there is no new production until August. The pink onions can be stored for six months. But it depends on climatic conditions. Our traditional storage methods cannot prevent rotting of onions due to high levels of humidity. Supply is maintained during the next four months by storing the March-April pink onion crop.

Our total production is 30 million tonnes per year. Our domestic need is about 15 million tonnes. We process a small quantity into paste and powder and export 1.5 million tonnes. Where does the rest of it go? There is considerable loss since onion is a perishable commodity. Losses are anywhere between 15% and 40%.

There is no shortage of onions, but India lacks a proper management system. Since this is a very climate sensitive crop, average productivity goes up significantly when the climate is good and it is not even 10 per cent of the average when the climate is poor. Due to this, the onion trade sees many ups and downs.

Moreover, the government’s export policy is also not stable. We need ambassadors at our foreign embassies who can speak on behalf of Indian agriculture to other countries. This has become necessary since our production has gone up significantly. We grow a surplus of cereals as well as horticultural crops. There are many other commodities that can be exported, but it needs proper management and vision so that Indian agriculture can get a better market globally.

There is a psychological factor at work in onion pricing. We are scared of shortage. When the retail prices of onions increase and the media makes it a big issue, the government feels pressured to act. Export is immediately banned. The media, government and consumers need to understand why prices go up. When there is less production of onions due to poor weather conditions prices are bound to go up. People have to understand this. This is accepted about other commodities, why not in the case of onions? I frankly don’t know.

In a global world, countries are free to import commodities from any that can assure them of good quality and regular supply. We have no policy to help our exporters. Our governments are only concerned that there should be no backlash from domestic consumers. Therefore their knee-jerk actions damage our export policies and the overall conditions for exports.

There are many factors that decide the price of onions by the time it reaches the consumer. For example, loading, labour, sorting, packing and transportation. There is a commission for all these activities. Costs increase at each stage of the handling process. All this means that there is a four-fold price increase in the final price of onions from the time the farmer sells his crop.

The 500-odd farmers of Gurha Kumawatan, a village in arid Rajasthan, are now millionaires thanks to polyhouse farming. Their hard work, innovation and unlimited ambition offers a path to prosperity for others in India.